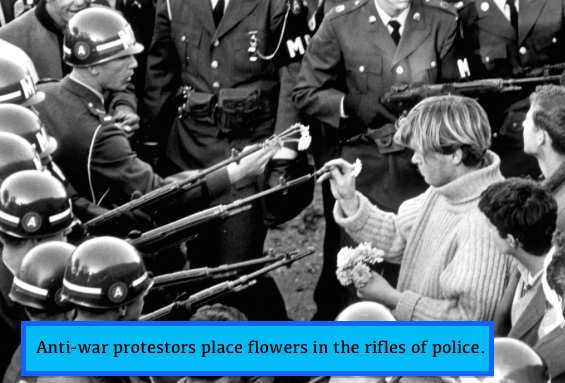

The year 1968 was one of the most tumultuous experienced among the American people; enormous social change was underway. Protests, pickets and riots that year marked the start of what emerged as the national Black Power Movement and the Women’s Movement, both efforts to use radical words and deeds to jump the nation into focusing on racial and gender inequality in all aspects of legal, social, professional and financial matters.

What ignited the nation’s divisive mood, however, was the increasing anger and frustration with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalating the American military presence in the Vietnam War and the increasing number of U.S. servicemen being killed and wounded.

What ignited the nation’s divisive mood, however, was the increasing anger and frustration with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalating the American military presence in the Vietnam War and the increasing number of U.S. servicemen being killed and wounded.

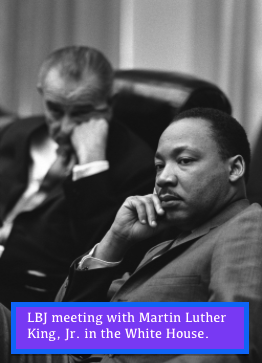

By 1968, LBJ’s Vietnam War began to overshadow the public appreciation and approval of his signing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and War on Poverty of social programs to eradicate malnutrition among the nation’s poor and offer greater educational opportunity to them.

The president’s wife, Lady Bird Johnson was best known for her “beautification” project launched with successful global media coverage beginning in 1965, well over a year after her husband had assumed the presidency upon the death of Kennedy.

The title was a feminine and seemingly inconsequential one, but the reality was that it approached numerous problems arising in national life at the time: environmental protection, land and water reclamation, preservation of national parks, planting of flowers, shrubs, bushes and trees in cities and towns, keeping large and ugly billboards off of national highways so drivers could see natural beauty instead, encouraging American and foreign visitors to help correct a balance-of-payment program by discovering the nation’s natural beauty as well as its historic sites.

The title was a feminine and seemingly inconsequential one, but the reality was that it approached numerous problems arising in national life at the time: environmental protection, land and water reclamation, preservation of national parks, planting of flowers, shrubs, bushes and trees in cities and towns, keeping large and ugly billboards off of national highways so drivers could see natural beauty instead, encouraging American and foreign visitors to help correct a balance-of-payment program by discovering the nation’s natural beauty as well as its historic sites.

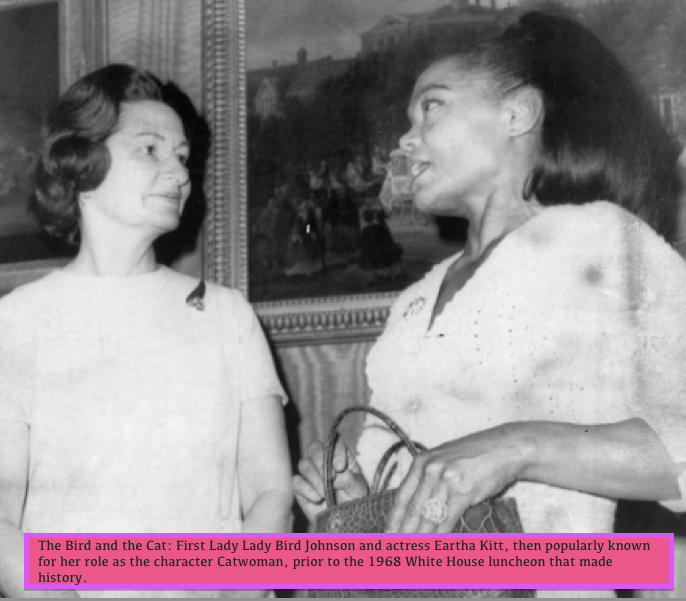

In early 1968, she hosted the first of a series of “Women Doer” luncheons, intended to gather women leaders from around the country to address a variety of growing or endemic problems. The first one, scheduled for January 18, 1968, fifty years ago today, was titled, “What Citizens Can Do to Help Insure Safe Streets.”

In her trademark southern accent, Mrs Johnson told the women invited to the event that it was a “grim subject for a pleasant meeting like this.”

The reaction to Mrs. Johnson and the three women speakers who followed seemed to only make a visibly nervous and agitated guest all the more upset.

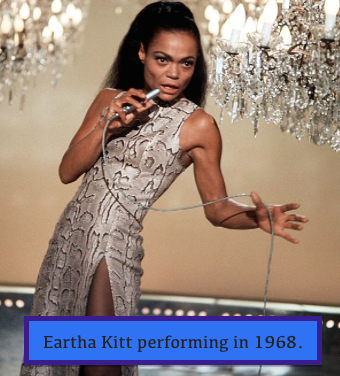

That guest was Eartha Kitt, already a legendary chanteuse who had made films and enjoyed a successful singing career in Paris. At that time, she was even more famous among the nation’s children, depicting the criminal character of “Catwoman” on the popular ABC-TV series Batman. She was African-American.

That guest was Eartha Kitt, already a legendary chanteuse who had made films and enjoyed a successful singing career in Paris. At that time, she was even more famous among the nation’s children, depicting the criminal character of “Catwoman” on the popular ABC-TV series Batman. She was African-American.

Unlike those like Mrs. Johnson who had been born into wealth and privilege and went on to earn a college degrees, Eartha Kitt had earned her own way through talent and determination, after enduring a harsh and isolating childhood and early years.

Never knowing her father, a white man who raped her black mother, and born on a South Carolina cotton plantation, she had been neglected and repeatedly abused. She hadn’t let it get in the way of her success.

Never forgetting where she came from, Eartha Kitt worked with in urban ghettos on youth programs, seeking to help young people from falling into crime and drug use. In the process, however, she also came away with a uniquely honest perspective on the issue of crime and juvenile delinquency.

Never forgetting where she came from, Eartha Kitt worked with in urban ghettos on youth programs, seeking to help young people from falling into crime and drug use. In the process, however, she also came away with a uniquely honest perspective on the issue of crime and juvenile delinquency.

Waving her hand so she could speak, while Mrs. Johnson told her “Eartha, you will be able to speak.”

When she did, the actress rose and unwound an angry monologue aimed at the First Lady and criticizing the President’s Vietnam War policy:

“…I have lived in the gutters. I know the youth of America today are not rebelling and are not hippies for no reason at all. We don’t have what we have on Sunset Boulevard for no reason. They are rebelling against something. There are so many things burning the people of this country, particularly mothers. They feel they are going to raise sons – and I know what it’s like, and you have children of your own, Mrs. Johnson – we raise children and send them to war. I am sorry Mrs. Johnson, if I am going to offend the President or you, but I am here to say the youth do not want to go to school because when they come out, they will be snatched from the mother and sent off to Vietnam. The boys of this country are doing everything they possibly can to avoid being drafted…They feel that ‘if I have any kind of life at all, I am going to enjoy it as best I can because I may not be here tomorrow…’If I get thrown in jail I don’t stand a chance of going off and being shot in Vietnam.’ They will smoke a joint and get high in order to avoid whatever it is to get shot at. You send the best of this country off to be shot and maimed. No wonder the kids rebel and take pot. In case you don’t know what that is, it is marijuana.”

Lady Bird Johnson was reported to have tears in her eyes, shocked at this first direct confrontation ever of a First Lady in the White House.

Lady Bird Johnson was reported to have tears in her eyes, shocked at this first direct confrontation ever of a First Lady in the White House.

She had, however, already encountered anti-war protests at Yale University and Williams College when she came to speak there. She gathered her thoughts and addressed Eartha Kitt:

“Because there is a war on – and I pray that there will be a just and honorable peace – that sty ill does not give us a free ticket not to try and work on bettering the things in our country that we can better. I am sorry I cannot understand as much as I should because I have not lived in the background as you have. Nor can I speak as passionately or as well as you can. But I think we must keep our eyes and our hearts and our energies focused on constructive aims. Violence will not help.”

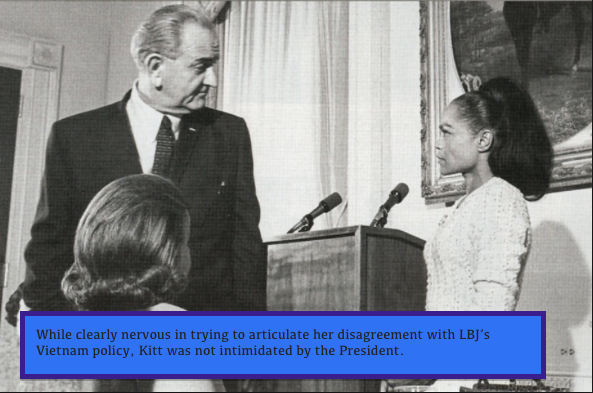

Alerted to what was going, President Johnson entered the luncheon held in the Family Dining Room. Kitt asked him in a rambling manner about when he would end the war, and why so many young men were being killed. It was an elliptical question and she got an elliptical answer.

The incident captured the next day’s headlines across the country.

There was an African-Americans pastor who criticized Eartha Kitt as a bad example of their race and apologized for her and a claim was brought to the attention of the White House that Kitt was “not well thought of by her people” because she been married to a white man. In contrast, Martin Luther King said she “made a very proper gesture” which “described the feelings of many persons.” An Oklahoma radio station banned the playing of Kitt’s songs, while one in New York staged a bitter satirical sketch of LBJ chiding Lady Bird for inviting “peacniks” to the manse.” Republican Congressional spouse Betty Ford praised Mrs. Johnson’s positive response while Democratic congressman Kastenmeier said Kitt spoke at “the right time in the right place.” Outside the White House the Women’s Strike for Peace picketed with signs that read “”Eartha Kitt speaks for the Women of America.”

There was an African-Americans pastor who criticized Eartha Kitt as a bad example of their race and apologized for her and a claim was brought to the attention of the White House that Kitt was “not well thought of by her people” because she been married to a white man. In contrast, Martin Luther King said she “made a very proper gesture” which “described the feelings of many persons.” An Oklahoma radio station banned the playing of Kitt’s songs, while one in New York staged a bitter satirical sketch of LBJ chiding Lady Bird for inviting “peacniks” to the manse.” Republican Congressional spouse Betty Ford praised Mrs. Johnson’s positive response while Democratic congressman Kastenmeier said Kitt spoke at “the right time in the right place.” Outside the White House the Women’s Strike for Peace picketed with signs that read “”Eartha Kitt speaks for the Women of America.”

The divided reaction to the Kitt-Johnson incident reflected the split in the nation about the war.

When Kitt left the luncheon she found that her White House limousine had been withdrawn. Upon arriving home, at Los Angeles airport, her anger was evident at an impromptu press conference:

When Kitt left the luncheon she found that her White House limousine had been withdrawn. Upon arriving home, at Los Angeles airport, her anger was evident at an impromptu press conference:

“I listened to all the ladies, They talked about flowers down the streets of American and making bigger and heavier street lights. I’m not against that – but I’m quite sure it does not squelch juvenile delinquency in any ways. Mrs. Johnson and Mr. Johnson did not start this particular Vietnamese ware. But they are in a position like the father and mother of the nation. We have been split. If Mrs. Johnson was embarrassed, that’s her problem.”

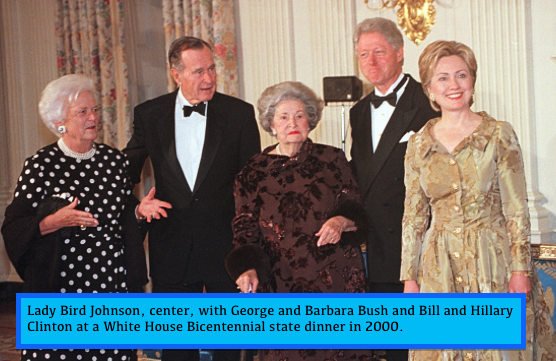

Lady Bird Johnson died at 95 years old in July of 2005. Eartha Kitt died at 81 years old in December 2008. Neither woman ever expressed regret for what they said. The former First Lady was rarely asked about the incident in her late interviews and never raised it. The actress, however, spoke about it often, especially in light of the fact that she believed the CIA had intentionally blackballed her from getting work as a singer and actress for a full decade afterwards.

Lady Bird Johnson died at 95 years old in July of 2005. Eartha Kitt died at 81 years old in December 2008. Neither woman ever expressed regret for what they said. The former First Lady was rarely asked about the incident in her late interviews and never raised it. The actress, however, spoke about it often, especially in light of the fact that she believed the CIA had intentionally blackballed her from getting work as a singer and actress for a full decade afterwards.

Here is footage of excerpts from the luncheon:

In 2007, Eartha Kitt recalled the incident in an interview with Newsweek.

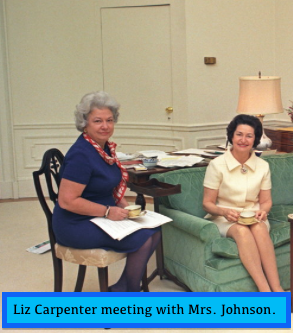

Two voices expressing the other perspective and providing background on it were recorded as part of the LBJ Library’s Oral History project, those of Liz Carpenter, the chief of staff and press secretary to Lady Bird Johnson, and Sharon Francis, who worked on policy issues as part of the First Lady’s staff.

Here is a transcript of the three recollections:

Sharon Francis, June 4, 1969

This Woman-Doers Luncheon, initiated by Liz and Mrs. Johnson, was to be built around the subject of anti-crime and women’s work in preventing or combating crime. It was turned over to me to develop speakers and the guest list. Cynthia and I both set to work on it, and secured, I think, very good, very successful and effective speakers. For the guest list we went to a number of different sources, including the Justice Department. I think I’m probably being kind, but my memory fails me as to the name of the aide in the Attorney General’s office with whom I worked on this. I asked particularly for people from arts and entertainment who might have really been out in the streets, or taking kids into drama groups or doing that kind of thing. This was a category person that Liz had asked for repeatedly as well.

This Woman-Doers Luncheon, initiated by Liz and Mrs. Johnson, was to be built around the subject of anti-crime and women’s work in preventing or combating crime. It was turned over to me to develop speakers and the guest list. Cynthia and I both set to work on it, and secured, I think, very good, very successful and effective speakers. For the guest list we went to a number of different sources, including the Justice Department. I think I’m probably being kind, but my memory fails me as to the name of the aide in the Attorney General’s office with whom I worked on this. I asked particularly for people from arts and entertainment who might have really been out in the streets, or taking kids into drama groups or doing that kind of thing. This was a category person that Liz had asked for repeatedly as well.

So this Justice Department person suggested Eartha Kitt. I’ve forgotten now just exactly what she had done, but it was that kind of thing of encouraging ghetto kids to use their time better. So she was put on the list. The list was duly cleared, as they always are, and everybody arrived for the luncheon. At these luncheons Mrs. Johnson almost always had one or two of us, usually Liz and me, but one or two of us invited as guests join her, particularly when we had worked hard on it. So I was a guest at the luncheon. I remember walking into the room with Eartha Kitt, admiring her fantastic figure, trying to get her to talk about anything. She was just as uptight as could be, looking around, rolling her eyes. I almost wondered if she were high, although I’m afraid I haven’t had enough experience with people who are high to know. But she was in a mood and certainly wasn’t going to communicate. Anyway, I did my best to be convivial and cordial as we went into the room.

President Johnson came in at some point during the luncheon. This was, incidentally, the first of the Women-Doers Luncheons that Mrs. Johnson had sponsored. He complimented the women on what they were doing and gave a nice little pep talk of two or three, or four minutes, just cordial and light. I don’t believe he asked for questions, I might be wrong, but at any rate Eartha Kitt jumped to her feet and said, “Mr. President” or “Mr. Johnson.” She posed a question to him which was hard to answer and antagonistic. I don’t think she mentioned Vietnam, but I think she just mentioned demoralization and not enough resources in the ghetto. She might have mentioned Vietnam, but, “My people and the people where I come from,” implying the ghetto. The President fielded it well, partially answered it to the degree it was answerable. It was the kind of question that had no answer, which she obviously knew when she made it. Then he slipped himself out of the room. My feeling was that he had done a very good job in a slightly awkward situation.

President Johnson came in at some point during the luncheon. This was, incidentally, the first of the Women-Doers Luncheons that Mrs. Johnson had sponsored. He complimented the women on what they were doing and gave a nice little pep talk of two or three, or four minutes, just cordial and light. I don’t believe he asked for questions, I might be wrong, but at any rate Eartha Kitt jumped to her feet and said, “Mr. President” or “Mr. Johnson.” She posed a question to him which was hard to answer and antagonistic. I don’t think she mentioned Vietnam, but I think she just mentioned demoralization and not enough resources in the ghetto. She might have mentioned Vietnam, but, “My people and the people where I come from,” implying the ghetto. The President fielded it well, partially answered it to the degree it was answerable. It was the kind of question that had no answer, which she obviously knew when she made it. Then he slipped himself out of the room. My feeling was that he had done a very good job in a slightly awkward situation.

Then a little while later, after one of the speakers, Eartha Kitt got to her feet again and said she just couldn’t let this go on without interrupting, that she had something very important to say. What she said was that the people in the ghetto were so demoralized over the war, over the sons and brothers and lovers going off to the war, that the moral climate was fractured. Resources which ought to be going to help the ghetto were going overseas to fight this cruel war. That was the theme of what she said. It seemed to me that she talked for five minutes. When you’re in a crisis situation you lose a sense of time and space pretty much, so my memory won’t be accurate on that point. But anyway she repeated herself a number of times–urgent, high-pitched, articulate, forceful, convincing, persuasive.

If she had said it once and stepped down it probably would have gone all right. But the more she talked the more she repeated herself, the more urgent she got. She had the platform, and she wasn’t going to let it go and really built up to quite a pitch. I at first just took it as an impassioned person. Then I realized that she was more than impassioned, that she was really very out of proportion psychologically, and I became apprehensive for Mrs. Johnson. I looked around the room, and my table was catty-cornered from Mrs. Johnson’s, and I was about equidistant to Mrs. Johnson from where Eartha Kitt was. I figured that if she lunged at Mrs. Johnson, and in my head that was quite a possibility, I could get there before the Secret Service could, because they were over by the door. So I got my chair back and was on the edge of my chair ready to beat off Eartha Kitt if she actually got violent. That didn’t happen, but I was that apprehensive about what was happening.

If she had said it once and stepped down it probably would have gone all right. But the more she talked the more she repeated herself, the more urgent she got. She had the platform, and she wasn’t going to let it go and really built up to quite a pitch. I at first just took it as an impassioned person. Then I realized that she was more than impassioned, that she was really very out of proportion psychologically, and I became apprehensive for Mrs. Johnson. I looked around the room, and my table was catty-cornered from Mrs. Johnson’s, and I was about equidistant to Mrs. Johnson from where Eartha Kitt was. I figured that if she lunged at Mrs. Johnson, and in my head that was quite a possibility, I could get there before the Secret Service could, because they were over by the door. So I got my chair back and was on the edge of my chair ready to beat off Eartha Kitt if she actually got violent. That didn’t happen, but I was that apprehensive about what was happening.

Mrs. Johnson finally stood up and got Eartha Kitt to be quiet. Reporters later said there were tears in her eyes. There may have been. She certainly was emotional. I didn’t see tears, but they could well have been there. What she said was one of the finest things I’ve ever heard her say, and in this case I know it was not rehearsed or planned beforehand.

Eartha Kitt’s nostrils were dilated, and she was sort of snorting. Then Mrs. Hughes, wife of the Governor of New Jersey, stood up, a nice, big, overweight, grandmotherly lady who said that she really just couldn’t let Miss Kitt go on the way she’d been going on, that she’d had four sons, all of whom had been in the war. Her first husband had been an officer in the air force; she was a proud and patriotic mother of proud and patriotic sons, and if some people were not willing to support our country’s commitment in this war she certainly was. And she knew of a great many Americans who were. Between Mrs. Johnson’s comments and hers this cut the tension in the room and cleared the air. Then essentially the meeting went on as it had been.

Of course, the press reported it considerably the next day. The press were present at the meeting. After the meal had been served we put up, oh, half a dozen chairs and invited a few of them just to come in and sit at the edge of the room to hear the speakers. Liz did some checking around afterwards on Eartha Kitt. We know that she went to a television station after leaving the White House and apparently intended to go on the air and say what she’d done. But it didn’t work out, and she didn’t do it. She left town.

Of course, the press reported it considerably the next day. The press were present at the meeting. After the meal had been served we put up, oh, half a dozen chairs and invited a few of them just to come in and sit at the edge of the room to hear the speakers. Liz did some checking around afterwards on Eartha Kitt. We know that she went to a television station after leaving the White House and apparently intended to go on the air and say what she’d done. But it didn’t work out, and she didn’t do it. She left town.

Mrs. Johnson was much too good a newsmaker not to be heartsick over getting bad press from an incident such as that. Mrs. Johnson had wanted to broadcast the constructive options the people had available to them. She had wanted to be using the White House as a forum for those individuals who were meeting the problems of crime head-on and doing something significant about them. For all these magnificent intentions, of course the story came out something very different and contrastingly tragic.

Eartha Kitt, November 10, 1967

I was sent an invitation by Lady Bird Johnson that said, ‘What Citizens Can Do to Help Insure Safe Streets.’ A car was sent for me and I walked into the White House by myself. The ushers at the door were in white gloves, and that made me feel like I was in the South again, which wasn’t a good feeling. Before the lunch, people were just standing around talking about the weather. At lunch we were all sat around these big tables, about 10 per table. It was, of course, all women. I remember the ladies at the table with me were more curious about the china we were eating off of than what we were there to talk about.

I was sent an invitation by Lady Bird Johnson that said, ‘What Citizens Can Do to Help Insure Safe Streets.’ A car was sent for me and I walked into the White House by myself. The ushers at the door were in white gloves, and that made me feel like I was in the South again, which wasn’t a good feeling. Before the lunch, people were just standing around talking about the weather. At lunch we were all sat around these big tables, about 10 per table. It was, of course, all women. I remember the ladies at the table with me were more curious about the china we were eating off of than what we were there to talk about.

It was very unnerving for me. I felt the women were a little nervous, too, because of the atmosphere. After dessert the question was asked: what can be done about the beautification of America? And they went around the room, calling on people to give their opinion. It was mostly about planting trees and flowers and such. I raised my hand several times and Lady Bird kept saying, ‘You’ll get your turn, Eartha.’

When I finally did I repeated the question that was supposed to be the topic, and everything got quiet. They were all fine to keep talking about planting seeds along Route 66, but I was there to say the real work needed to be done through the educational system. I was the last person to speak, and as soon as I finished, everyone disappeared.

One lady who remained came up to me and said, ‘I have eight sons and I would gladly donate them all to Vietnam.’ I said, ‘I’m sorry, I can’t talk to you.’ When I got outside, suddenly I didn’t have a car anymore. I had to take a taxi back to the hotel. That about said it.

Liz Carpenter, April 4, 1969:

Eartha Kitt was chosen [as a guest] because she had testified in behalf of the President’s bill… on juvenile delinquency, and she had talked about what could be done on crime. If Eartha Kitt had come to the White House and told about the ballet classes that she teaches as a volunteer in Watts, it would have been a whole different ballgame. But she came and for reasons that I do not know but only could guess that she was the declining actress looking for a stage. She decided to throw in the Vietnam War and get fiery about it, and so she really undermined her own race because for the first time, a first lady was trying to tackle the subject of crime and she diverted everyone’s attention to Eartha Kitt and Vietnam while someone was trying to accomplish her problems.

Eartha Kitt was chosen [as a guest] because she had testified in behalf of the President’s bill… on juvenile delinquency, and she had talked about what could be done on crime. If Eartha Kitt had come to the White House and told about the ballet classes that she teaches as a volunteer in Watts, it would have been a whole different ballgame. But she came and for reasons that I do not know but only could guess that she was the declining actress looking for a stage. She decided to throw in the Vietnam War and get fiery about it, and so she really undermined her own race because for the first time, a first lady was trying to tackle the subject of crime and she diverted everyone’s attention to Eartha Kitt and Vietnam while someone was trying to accomplish her problems.

Eartha Kitt was suggested by the committee on the Hill that had run the hearings…I checked her out with two or three people at Justice and so forth, and asked if her name had ever shown up on any kind of ad protesting the President on Vietnam. It had not. It still has not.

In fact, as far as the Vietnam, the day that she appeared at the White House luncheon, she had asked a congressman to make an appointment for her at the Pentagon to see about going to Vietnam to entertain the troops. She did not believe enough entertainers were helping our boys. She canceled the invitation and the most surprised man in Washington was the Army colonel who she had an appointment with at four o’clock that day to work out a two-week trip touring in Vietnam; when he heard on the radio of her blast at the First Lady.

I think that she was always looking for headlines. I think they could have taken any kind of turn. I have wondered if the militant blacks got hold of her before she came to the White House or afterwards. She was seen with Stokely Carmichael leaving the Shoreham Hotel where she was staying. To the best of my information, and I did considerable checking, it happened in an impromptu way. She has a lot of problems. One of them was she was dieting and she didn’t eat a bite at the lunch. She had had some drinks. The second thing is she is a declining actress looking for publicity, and she was determined she was going to get [it]. Her agent had called me and asked me if she could make a speech. I said, “No, we have speakers.” And so she didn’t. But it ended up that she got the headlines.

However, here again, Mrs. Johnson was determined to convert what that bad blast had been into constructive action. We got ten thousand letters on the Eartha Kitt thing. The phones rang off the hook, and I had the staff in my office to take every single phone call…They were 95 per cent in behalf of Mrs. Johnson and indignant that anyone would talk to a first lady that way as a guest in their home.

But about five national organizations put out prime kits as a result of hearing about it. Maybe they w0uldn’t have heard about it if there hadn’t been that angry voice, so that we got our story out. And to every one of the ten thousand letters, l’ve sent a letter saying, “It is too bad that an angry voice tried to turn our attention, but if you were serious about

doing something about crime in your city, here are eighteen things you can do, and we listed each one of the eighteen things, such as, “You can have a survey and check on the amount of street lighting in a neighborhood because where streets are lighted, less crime occurs.”

And so good things came out of it, but it was an awful moment, of course…..More we heard in the terms of resolutions passed by national organizations on “This will be one of our projects.” And the Business and Professional Women’s Clubs got out a crime kit using our list of what you can do. The National Federation of Women’s Clubs passed a resolution applauding Mrs. Johnson. Interestingly enough, even the National Association of Colored Women passed [supportive] a resolution.

[In private, Mrs. Johnson felt] deep despair, because no one enjoys having such an ugly exchange. And it came as such a shock, and I think she was very blue about it. I think she really, you know, you reexamine your own thoughts and think how in the heck did this woman get on the list? And that was one of the questions we had to answer. You know, you think, “Gosh, I should have been smarter than to invite her.” We didn’t know much about her. The only thing we knew was the record that she was one of the few persons in the performing arts who had ever made a statement on crime.

Categories: First Ladies, Hollywood

Tags: Eartha Kitt, Jr., Lady Bird Johnson, Lyndon B. Johnson, Martin Luther King, Vietnam War

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders

Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health

Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health

I’ve never heard of this luncheon. Really interesting. Lady Bird Johnson was a wonderful First Lady, and Eartha a very talented actress and singer.