Melania Trump unveiling her Be Best program, Monday, May 7, 2018. (Screen shot of White House video)

The news breaking on Monday, May 14, 2018 that First Lady Melania Trump was at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for kidney surgery wasn’t learned through leaks to the New York Times, nor revealed by a lawyer on cable news nor wild-eyed gossip on some chatty entertainment website. It was delivered straightforward and unambiguously from her communications director Stephanie Grisham:

“This morning, first lady Melania Trump underwent an embolization procedure to treat a benign kidney condition. The procedure was successful, and there were no complications.”

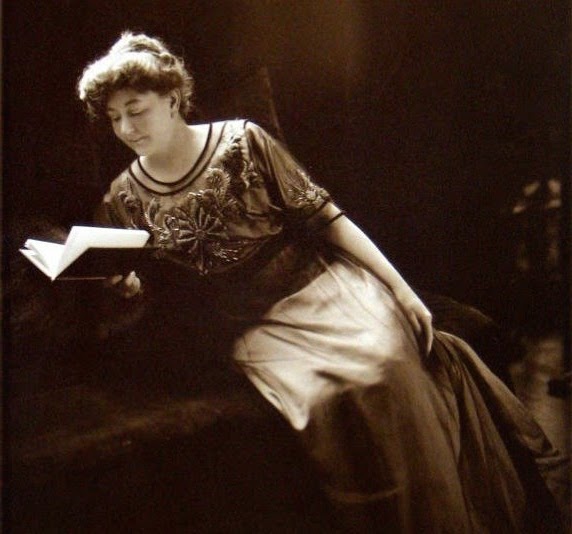

Ellen Wilson.

The media and the public have come to regard disclosures of medical information about a First Lady as falling within their legitimate right to know.

After all, there is the potential emotional affect of a wife’s health on a President, no more dramatic example of this being the weeks of August 1914 when President Woodrow Wilson was simultaneously coping with his wife Ellen’s terminal kidney and war breaking out in Europe.

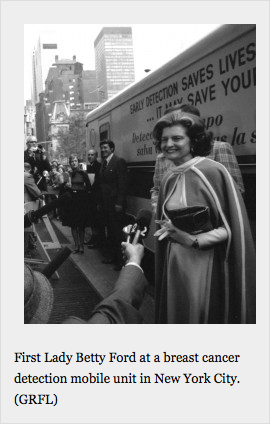

Betty Ford.

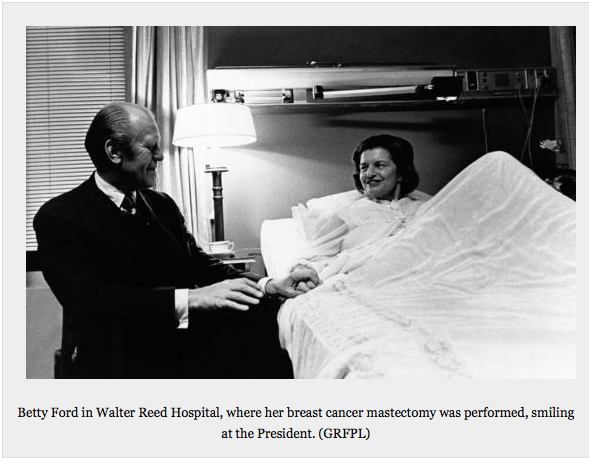

A First Lady facing a medical crisis can end up saving lives and opening awareness on a disease. The greatest example of this is when Betty Ford decided to disclose she had undergone a examination for a lump in her breast, learned it was cancer and underwent a mastectomy, thereby saving millions of lives.

Laura Bush.

And yet, in truth, First Ladies are technically not public officials. Though it has been more than a century since there has been a presidential wife who lived in the White House yet refused to undertake any public responsibilities that is still within their legitimate right.

As is deciding not to have a medical condition reported, an example of this being the startlingly recent one of Laura Bush’s 2006 skin cancer.

No matter how many examples may have been set before Melania Trump, history shows that when it comes to disclosing their health issues, First Ladies will do as they usually do on matters involving their private matters affecting their public lives: what is right for them and not what was right for those before them.

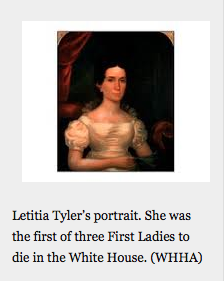

Three First Ladies died in the White House, Letitia Tyler in 1842, Caroline Harrison in 1892 and Ellen Wilson in 1914. It was not until after the first one had died and just before the second and third died, however, that the public learned of the loss within the presidential household.

Throughout most of presidential history, the true state of health of the nation’s leader was often kept hidden from the media of the day, and thus the public, largely for political reasons. The idea of a weak Chief Executive, he and his political circle would fear, would lead to challenges of his political power by the opposition. It could also potentially spread a degree of national fear and hysteria that could destabilize the American economy.

Throughout most of presidential history, the true state of health of the nation’s leader was often kept hidden from the media of the day, and thus the public, largely for political reasons. The idea of a weak Chief Executive, he and his political circle would fear, would lead to challenges of his political power by the opposition. It could also potentially spread a degree of national fear and hysteria that could destabilize the American economy.

When it came to their wives, however, the issue was largely one of propriety, the idea that public discussion of anything physical about a woman, let alone one who held a position that was imbued with the symbolism of the highest social status of the nation.

It was only when, in the expectations that a presidential spouse would appear in public and endure the physical rigor of performing as hostess in the White House, that there was anything remotely resembling public disclosure about chronic health conditions of First Ladies.

In many respects, those First Ladies who had chronic conditions that were not fatal ended up becoming more honest about the true state of their health.

In some ways, simple confirmation of the health conditions of nineteenth century presidential spouses, without great detail, were more direct and honest than those who followed.

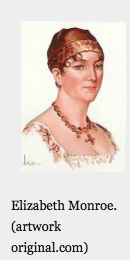

As early as the eight-year tenure of Elizabeth Monroe, from 1817 to 1825, the public were informally informed of the fact that the First Lady was not in robust health simply because of the presence of her adult daughter Eliza Hay at public entertainments either in support of her mother as hostess or substituting for her.

What not even those close to Mrs. Monroe, outside of a circle of about a dozen family members including her two daughters, sons-in-law, sister, nephews, and nieces, is that she suffered with symptoms associated with what was then called “the falling sickness,” a euphemism for epileptic seizures.

What not even those close to Mrs. Monroe, outside of a circle of about a dozen family members including her two daughters, sons-in-law, sister, nephews, and nieces, is that she suffered with symptoms associated with what was then called “the falling sickness,” a euphemism for epileptic seizures.

The first death of an incumbent First Lady naturally made the newspapers of the day, but within the news stories were the most specific references made to that point about the facts about the poor health that had impaired her ability to assume a public role.

The Camden Journal printed on September 21, 1842, from an original news story that appeared in the Madisonian newspaper of Washington, D.C. even went into great detail on her funeral and the effect on the family, an early and rare example of media and public intrusion into the private life of a presidential family.

Newspaper coverage of the first death of an incumbent First Lady, Letitia Tyler in 1842.

When Tyler inherited the presidency, it was widely reported that he was a widower. A subsequent news report in a Pennsylvania newspaper corrected this, pointing out that Mrs. Tyler was “alive” by making another error in reporting she was “in good health.” Only a few newspapers got the facts right, and it seems that but one reported what was wrong with her, using the word “stroke.”

Then again, the information was gleaned from inside reports: the Tyler White House issued nothing even close to a modern-day concept of a press release.

Some historians later cast doubt on the claim of uncertain health of Peggy Taylor, suggesting that it was a false story put out by the White House because this First Lady did not want to assume a public role.

An October 3, 1848 squib in the Daily Crescent of New Orleans, reprinting the excerpt of a May 1848 letter from a Louisiana woman to the Baton Rouge home of Mrs. Taylor before her husband was elected president, however, confirms the truth of it, the eyewitness describing her as “sociable, polite….a plain, agreeable lady, but apparently of rather delicate health.”

An October 3, 1848 squib in the Daily Crescent of New Orleans, reprinting the excerpt of a May 1848 letter from a Louisiana woman to the Baton Rouge home of Mrs. Taylor before her husband was elected president, however, confirms the truth of it, the eyewitness describing her as “sociable, polite….a plain, agreeable lady, but apparently of rather delicate health.”

This did not negate the fact that it was true that she did not wish to assume a public role, a condition that her poor health gave further rational. Interestingly, the scant national news coverage of Mrs. Taylor during the year and a half of her husband’s presidency did not make reference to her health or even slightly suggest what was wrong with her, except for mention of the fact that she sought refuge from Washington’s heat at a cool natural spring spa.

The worst that ailed Abigail Fillmore was reported to the public as a poorly healed broken ankle, preventing her from standing for lengthy periods on the reception line at the public receptions.

Since the November 25, 1850 New York Herald cast the presence of her daughter Abby Fillmore as a supportive role who “sustained her mother admirably” rather than ever being a substitute for the president’s wife, the First Lady was perceived to have been in robust health.

When, however, just days after her husband’s administration ended and the former First Lady seemed to linger for an unusually longer period of time in her capital hotel room, the press felt free to fully detail her slow demise to pneumonia.

When, however, just days after her husband’s administration ended and the former First Lady seemed to linger for an unusually longer period of time in her capital hotel room, the press felt free to fully detail her slow demise to pneumonia.

Had this occurred just days before the Fillmore presidency had concluded, it is difficult to judge whether her deteriorating physical condition would have been so aptly chronicled or if the era’s usual propriety about revealing such personal facts about the private life of one with the highest status would have prevented it.

A stroke or pneumonia were common enough among families that many Americans considered vulnerability to either condition to be somehow acceptable, whereas other chronic conditions such as cancer or tuberculosis carried a stigma and thus an especially indelicate fact to publicly state about a President’s wife.

When her husband was first nominated for the presidency in the summer of 1852, any mention of Jane Pierce almost always described her as being ill or in unpredictable condition. The Portsmouth Inquirer of August 13, 1852 even carried a statement by the family’s physician of seven years making reference to “the delicate health of Mrs. Pierce.”

Media coverage of her over the course of the presidency that showed she was well and then, without warning, not well made clear that she suffered from some type of chronic, rather than fatal illness, but there was no mention of the word tuberculosis or even references to her occasional difficulty breathing or any lung trouble.

Media coverage of her over the course of the presidency that showed she was well and then, without warning, not well made clear that she suffered from some type of chronic, rather than fatal illness, but there was no mention of the word tuberculosis or even references to her occasional difficulty breathing or any lung trouble.

Instead, her sallow appearance and lack of energy was all written off as being due to grief and depression over the sudden death of her eleven year old son just three months before her husband’s inauguration. She did suffer from depression, badly. But she also endured a lifetime of tuberculosis.

Eliza Johnson’s physical frailty and thus inability to “do the honors” at the White House when she and her children joined President Andrew Johnson on June 19, 1865 proved worthy of public reporting as a way of explaining why her daughter Martha Patterson would substitute for her.

Like Jane Pierce, the fact that Eliza Johnson had tuberculosis, however, was not printed. Instead, Patterson’s assumption of the public First Lady role was justified as “owing to the ill health of Mrs. Johnson.”

Like Jane Pierce, the fact that Eliza Johnson had tuberculosis, however, was not printed. Instead, Patterson’s assumption of the public First Lady role was justified as “owing to the ill health of Mrs. Johnson.”

Within just a few short weeks of becoming First Lady in 1881, Lucretia Garfield was hit by a bad case of malaria.

From the moment she had to absent herself from public receptions, the White House issued daily reports on her condition.

While it did not go into great details, the press releases issued by the presidential physician on duty, did include her temperature and level of discomfort all the way through her eventual recovery.

While it did not go into great details, the press releases issued by the presidential physician on duty, did include her temperature and level of discomfort all the way through her eventual recovery.

It was a turning point in terms of not just media coverage of illness in the White House but of a woman in the public eye.

Yet the Garfield situation proved to be an anomaly, rather than being used as a precedent by either the White House or the reporters who covered it.

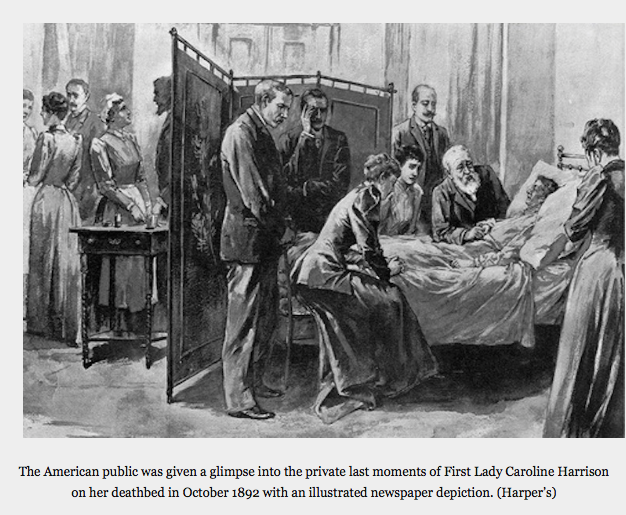

One may speculate as to why it was that Caroline Harrison’s cancer did not become public knowledge until she was on her death bed in October 1892.

One may speculate as to why it was that Caroline Harrison’s cancer did not become public knowledge until she was on her death bed in October 1892.

The fact that it was a fatal condition was surely a consideration, an effort to preserve the privacy of the family for as long as possible as it prepared for her loss. On the other hand, it is unclear how much advance notice the President and his family truly had to realize her death was inevitable.

Nevertheless, when this second First Lady to die in the White House occurred, it rated as front-page news stories.

Another turning point in First Lady history was the fact that one of the weekly illustrated newspapers, Harper’s had even seen fit to depict the sick woman on her deathbed. (see the lead image at top).

It was not something that had been done eleven years earlier when Mrs. Garfield was quarantined to a White House sickroom, although there were numerous images printed of her at the bedside of her husband as he struggled to recover from the bullet wounds that eventually killed him.

It was not something that had been done eleven years earlier when Mrs. Garfield was quarantined to a White House sickroom, although there were numerous images printed of her at the bedside of her husband as he struggled to recover from the bullet wounds that eventually killed him.

As the nation entered the 20th century, there would be more enlightenment about the nature of many perplexing illnesses that affected women.

Yet, just as the role of First Lady is one defined by highly personal criteria, so too would be the policy about releasing information about such a personal issue as their health.

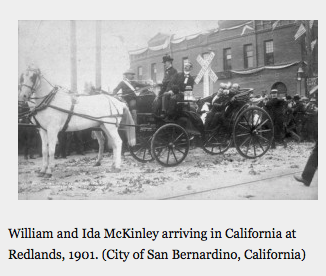

In May of 1901, the President and Mrs. McKinley were making an historic transcontinental tour of the United States by train, progressing south from Washington to New Orleans and then to the western states, including the First Lady making a brief dash across the border to attend a breakfast in Mexico in her honor, while her husband attended ceremonies in El Paso, Texas.

In May of 1901, the President and Mrs. McKinley were making an historic transcontinental tour of the United States by train, progressing south from Washington to New Orleans and then to the western states, including the First Lady making a brief dash across the border to attend a breakfast in Mexico in her honor, while her husband attended ceremonies in El Paso, Texas.

All along the way, Ida McKinley heartily greeted well-wishing citizens, but in the process the repeated handshake clasping against the diamond rings she wore on her fingers, left small cuts.

As the train proceeded through the desert to the west coast, the dust, sand and silt kicked up by the rail cars inevitably blew through the presidential car, covering everything from the furnishings to the cut hand of the First Lady.

By the time a finger infection which was first detected in Los Angeles developed into high fever, blood poisoning and near-death upon their reaching the Monterey Peninsula, a sudden change in the President’s public schedule (permitting him to remain with her) necessitated public disclosure of the reason.

By the time a finger infection which was first detected in Los Angeles developed into high fever, blood poisoning and near-death upon their reaching the Monterey Peninsula, a sudden change in the President’s public schedule (permitting him to remain with her) necessitated public disclosure of the reason.

Determining that the First Lady’s grave condition could best be treated in the nearby city of San Francisco, the traveling White House moved with her to that nearby city, issuing two bulletins a day to keep the nation informed of her condition.

A month later, government medical consultants who conducted further blood tests and physical examinations on her provided the media with the startling speculation that her heart function may have been affected; the White House made no effort to deny or censor this.

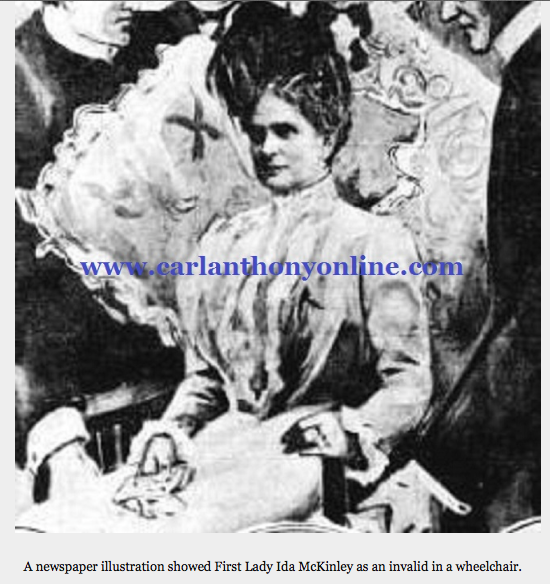

And yet, pre-dating and simultaneous to all this was the McKinley White House policy of refusing to acknowledge, clarify or elaborate the repeated news reports of her vaguely described “nervous illness,” with symptoms of “fainting.” We know now that this was because the nervous system dysfunction in question was epilepsy.

And yet, pre-dating and simultaneous to all this was the McKinley White House policy of refusing to acknowledge, clarify or elaborate the repeated news reports of her vaguely described “nervous illness,” with symptoms of “fainting.” We know now that this was because the nervous system dysfunction in question was epilepsy.

During the McKinley Administration there were great strides in the expanding professional field of neurology which established seizure disorder to be a brain and nervous system condition and not the result of a mood disorder.

The general public, however, still held fast to the primitive belief that epilepsy was a form of insanity. Fearing the political repercussion of such association with the First Lady, the President was iron-clad in refusing to even acknowledge her seizures when they were occurring.

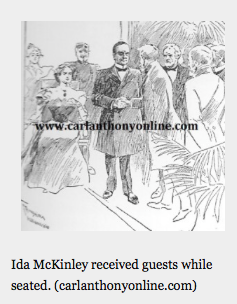

At the least, the public knew something was wrong with Ida McKinley, simply by the fact that she always sat during receiving lines while her husband stood alongside her.

At the least, the public knew something was wrong with Ida McKinley, simply by the fact that she always sat during receiving lines while her husband stood alongside her.

Might the public understanding of epilepsy have advanced more rapidly had the McKinley Administration disclosed the truth about the First Lady’s condition? Most likely.

Was it the responsibility of the McKinleys to do so?

Despite their public roles and care by federally-salaried physicians the couple exercised their right to make a personal choice on how much they chose to disclose on the matter, determining to do so only when the First Lady’s health had a potential impact on the President’s ability to function.

Of course, there were many situations when it could be argued that, unlike the feared death of McKinley’s wife that a health condition or medical crisis of a presidential spouse did not affect a President and his performance and thus did not qualify as news the public had a right to know.

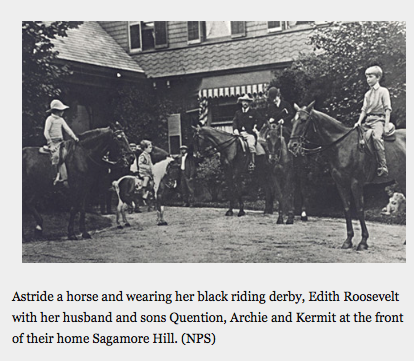

While it was saddening for President Theodore Roosevelt when his wife Edith Roosevelt suffered a miscarriage while she was First Lady, this information was not learned until her biography was published some four eight decades after the fact.

While it was saddening for President Theodore Roosevelt when his wife Edith Roosevelt suffered a miscarriage while she was First Lady, this information was not learned until her biography was published some four eight decades after the fact.

Sometimes, a halfway measure has also been employed.

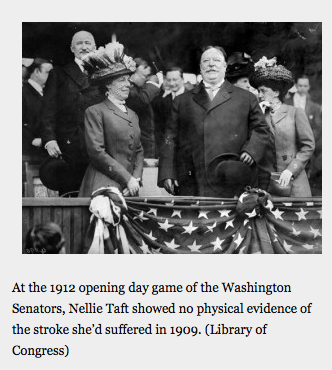

In 1909, for example, following her suffering of a stroke, First Lady Nellie Taft lost the ability to speak and thus cancelled all her public appearances. For months she struggled to learn again how to speak, her sisters and daughter aiding in social duties.

By her absence, the press and the public knew something was wrong. The White House released a degree of what was truthful facts about her condition, but did not make all of it publicly-known, including the fact that she had lost but was regaining her power of speech.

Rather than use the word “stroke” in more abstractly, yet honestly, referred to it as a “nervous condition.”

Rather than use the word “stroke” in more abstractly, yet honestly, referred to it as a “nervous condition.”

One is whether the First Lady in question is seeking medical care at the expense of public funds: in almost all instances this is the case, presidential family members being given such care by army and navy surgeons and physicians of high rank and skill.

By the early twentieth century, there seemed to be a precedent set that determined the public’s right to know about the health of a First Lady.

The decision had come to be truly based on that one elusive and subjective question: how is the President’s ability to fulfill his constitutionally-mandated duty being impeded by matters involving the health condition of a spouse?

We know now, for example, that the kidney disease which ultimately killed Ellen Wilson just a year and a half into her tenure as First Lady, deeply distracted President Wilson just as war was breaking out in Europe.

Following her August 1914 death in the White House, Wilson sunk into such a severe depression that his physician even feared he might become suicidal.

Following her August 1914 death in the White House, Wilson sunk into such a severe depression that his physician even feared he might become suicidal.

Yet it was not until days before Mrs. Wilson died that the media and thus the public first learned the full story on her terminal condition.

This could not be blamed on the President or his daughters but rather the First Lady herself. While not concerned about public knowledge of her condition, she asked her physician to not inform her family of just how desperate her condition truly was until the last possible minute, hoping to spare them a prolonged anguish over her.

Of course, it had the effect of also being able to honestly withhold the information from the media and public.

In the Jazz Age, Florence Harding wanted the public to be provided with the full details about the kidney dysfunction – but only when it reached the point of nearly killing her in September of 1922.

For several days, as the First Lady’s life hung in the balance, the entire country was able to follow her condition with the release of detailed medical bulletins, which included explicit physical descriptions.

For several days, as the First Lady’s life hung in the balance, the entire country was able to follow her condition with the release of detailed medical bulletins, which included explicit physical descriptions.

This sort of policy when it comes to First Ladies and their health might not be the full truth, but it is better than no truth at all.

As the century progressed along with medical science and the new and emerging forms of technology, from radio to sound newsreels to television, however, there were a number of First Ladies with either chronic health conditions or medical care that was unreported, denied or downplayed by the White House.

Grace Coolidge’s heart palpitations went entirely unreported in the media as she neared the end of her tenure, although there were reports that President Coolidge’s decision not to seek re-election in 1928 may have been out of concern for his wife’s apparently increased tiredness.

Were it not for a passing reference in a private letter to a friend about her doctor ordering her to radically reduce her intake of caffeine from coffee consumption, none outside of the family would have known.

Were it not for a passing reference in a private letter to a friend about her doctor ordering her to radically reduce her intake of caffeine from coffee consumption, none outside of the family would have known.

Similarly, when Bess Truman was found to be suffering from high-blood pressure, outside of her family it was only the White House kitchen staff that might have suspected this as the reason for the sudden order of low-sodium meals.

It was never information that reached the public, even by rumor. Then again, Mrs. Truman managed it carefully, living with the condition until her death at age 97 years old and it never affected the President’s ability to perform his duties.

It was never information that reached the public, even by rumor. Then again, Mrs. Truman managed it carefully, living with the condition until her death at age 97 years old and it never affected the President’s ability to perform his duties.

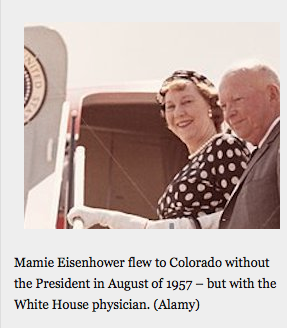

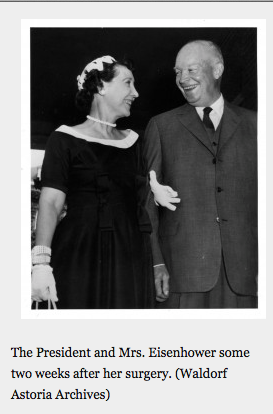

In August of 1957, Mamie Eisenhower made an annual five-day summer visit to her mother in Denver, Colorado, Unlike previous times, however, she stayed in the city’s Brown Hotel. The big event of her time there was her commitment to speak at the dedication of a local park named in her honor.

The First Lady appeared at the ceremony, but left those gathered disappointed by simply making a few remarks and then taking her leave. Her brief appearance at the park proved to be only one of two times she left her hotel suite, a schedule very much unlike her previous visits home.

President Eisenhower had not joined her for the trip, but the White House physician Howard Snyder had. That raised some suspicions among the local press corps.

President Eisenhower had not joined her for the trip, but the White House physician Howard Snyder had. That raised some suspicions among the local press corps.

It was soon learned that shortly before, he had also accompanied Mamie Eisenhower to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C. and stood watching as an army gynecologist performed a two-hour hysterectomy on the First Lady. After the surgery she recovered in the presidential suite, visited by the President eight hours later.

It was only under some pressing by the White House press corps that the President’s Press Secretary Jim Hagerty had finally disclosed all this, yet refrained from using the clinical expression “hysterectomy,” by instead making euphemistic reference to it as “similar to those that many women undergo in middle age.”

It was only under some pressing by the White House press corps that the President’s Press Secretary Jim Hagerty had finally disclosed all this, yet refrained from using the clinical expression “hysterectomy,” by instead making euphemistic reference to it as “similar to those that many women undergo in middle age.”

Pressed if the operation was, in fact, an hysterectomy, he replied that he would “not go beyond” the “original statement.”

It illustrated that, just as the technology of media or the evolution of medical information or the effect on a president’s ability to carry out his duties, the societal perceptions of womanhood was just as powerful a factor in determining what the public is told about the health of First Ladies.

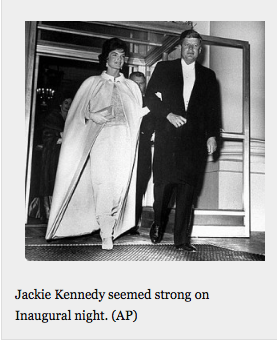

She was the vision of youth and at 31 years old, Jackie Kennedy was the third youngest First Lady in history. She played tennis, loved speed walking for miles on end, swam like a pro and enjoyed waterskiing to keep her thighs trim.

She was the vision of youth and at 31 years old, Jackie Kennedy was the third youngest First Lady in history. She played tennis, loved speed walking for miles on end, swam like a pro and enjoyed waterskiing to keep her thighs trim.

So, on the night of January 20, 1961, when just eight weeks after she had been rushed into Georgetown University Hospital for emergency cesarian surgery to give birth to her son, Jacqueline Kennedy appeared in her white cape and gown at the Inaugural Balls, the world looked upon her as the vision of of beaming health. In truth, she was anything but that.

The press had also begun to depict her as “mysterious” and “elusive” because she failed to appear at many of the large, crowded events held before the Inauguration other than the Inaugural Concert and the Inaugural Gala.

After the Inaugural ceremony and parade, she vanished even from the gathered members of her paternal and maternal family and those of her husband’s, during s White House Reception held before the Inaugural Ball.

When the time came for her to join the new President and exit through the North Portico, still and motion picture cameras were fixated on her serene face, as she seemed to float out the door.

When the time came for her to join the new President and exit through the North Portico, still and motion picture cameras were fixated on her serene face, as she seemed to float out the door.

And while she appeared at the first few Inaugural Balls, she just as soon disappeared for the rest of the night, returning to the White House while John F. Kennedy continued on to the other balls.

In fact, she was suffering what she later described as clinical exhaustion. Once she had returned to the executive mansion, she admitted that she entirely “collapsed.” It had only been the administration of a narcotic drug by the president’s doctor, Janet Travell, that she had been able to muster enough strength to appear at the balls.

This fact was something the press would never learn during her time in the White House. It was only after she had left and made casual reference to the fact that she got through Inauguration Day only by using dexedrine, a frequently prescribed amphetamine medication intended to infuse “energy” into the system, that the world learned the truth.

The only occasions when the White House released any information on the First Lady was when she failed to show up at a public appearance. The fact that she did indeed suffer with frequent sinusitis was often given as the reason for her absence. That is, until the day when she showed up instead at a theater performance in New York.

The only occasions when the White House released any information on the First Lady was when she failed to show up at a public appearance. The fact that she did indeed suffer with frequent sinusitis was often given as the reason for her absence. That is, until the day when she showed up instead at a theater performance in New York.

It was only towards the end of her tenure, when Jackie Kennedy again gave birth that the world would learn the medical details about this most private of First Ladies. Every detail was reported because the press corps was closely following, down to the minute the premature birth and sudden death of her baby, Patrick, in August of 1963.

Escorted by her husband, Jacqueline Kennedy leaving Otis Air Force Base hospital following emergency delivery of her son Patrick who died days later.

Two months later, as she endured the aftermath of her husband’s assassination, there was no mention of any medication she may have needed or requested or turned down then or in the days that followed. The old sense of propriety about keeping the matter of a woman’s health private, especially given the terrible circumstances, was again employed for the president’s widow.

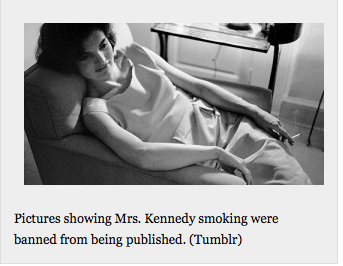

ike millions of women who believed the advertising campaigns that promoted cigarette smoking as a way to stay calm and keep thin, Jackie Kennedy was a heavy cigarette smoker but White House photographers were ordered to never snap her in the act of puffing and if, by accident, they captured her doing so the pictures were banned from public release.

More remarkably, the commercial photographers who regularly captured her on film as she went about her private business adhered to an unwritten rule of not publishing images of the First Lady smoking.

More remarkably, the commercial photographers who regularly captured her on film as she went about her private business adhered to an unwritten rule of not publishing images of the First Lady smoking.

A decade later, after the Surgeon General warnings about the dangers of cigarette smoking, this same unwritten rule the press had applied for Jackie Kennedy continued for Pat Nixon.

Although there were not even any known images showing this First Lady smoking, it was a fact known to several reporters who followed her closely.

Yet without first checking with the First Lady, Mrs. Nixon’s press secretary spontaneously and steadfastly insisted to the reporters that she did not smoke cigarettes.

Yet without first checking with the First Lady, Mrs. Nixon’s press secretary spontaneously and steadfastly insisted to the reporters that she did not smoke cigarettes.

Some twenty years after her time in the White House, Mrs. Nixon died of lung cancer.

In the contemporary world of social and digital media, every possible detail is reported about anything pertaining to the President and has come to be considered fair game for public dissemination, including medical information. Should we also expect that the health of our First Ladies be made public?

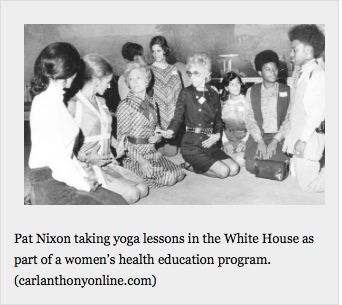

Since the incumbency of Pat Nixon as First Lady in the 1970s, matters of health care, preventative health measures, public awareness about early warning signs of specific illnesses and those physical problems which particularly affect American women have become among primary issues First Ladies since then have sought to address in various forums.

Since the incumbency of Pat Nixon as First Lady in the 1970s, matters of health care, preventative health measures, public awareness about early warning signs of specific illnesses and those physical problems which particularly affect American women have become among primary issues First Ladies since then have sought to address in various forums.

Today, there are good arguments both that the public has a right to know the details about the First Lady’s health or that disclosure of such sensitive matters is a prerogative of the individual in question.

Outside of this one can find no greater example of the dramatically positive affect of full disclosure regarding a First Lady’s health than the 1974 breast cancer and mastectomy of Betty Ford.

Previous to this incident, discomfort in the discussion of breast cancer prevention and detection had kept the matter one that remained largely verboten in the general public discussion and news media.

Quite literally overnight, that societal norm shifted because of Mrs. Ford’s conscious decision to permit full public disclosure; as a result untold hundreds of thousands of lives were likely saved as not only American but non-American women sought out the necessary medical procedures ensuring early detection.

Quite literally overnight, that societal norm shifted because of Mrs. Ford’s conscious decision to permit full public disclosure; as a result untold hundreds of thousands of lives were likely saved as not only American but non-American women sought out the necessary medical procedures ensuring early detection.

This new sense of freedom about discussing the issue was greatly furthered when Betty Ford decided to assume the role of a national spokesperson about it, doing all she could to help women and their families more comfortable about discussing breast cancer.

Some one dozen years later, another First Lady discovered she had breast cancer and sought immediate treatment of it.

In line with the detailed disclosures made about President Reagan’s health challenges, when Nancy Reagan considered her highly committed schedule in the months ahead, the First Lady opted to have a complete mastectomy.

She realized it would alter her body permanently versus the choice of a partial mastectomy and the weeks of chemotherapy that would have to follow with that choice.

She realized it would alter her body permanently versus the choice of a partial mastectomy and the weeks of chemotherapy that would have to follow with that choice.

Mrs. Reagan’s office was implored against a complete mastectomy and urged by advocates to opt for a partial mastectomy. She decided the complete mastectomy was the right personal choice for her, due to the time would have required her to shift focus from her support to the President at a time when she felt he needed her most.

Thus, with a First Lady deciding to fully go public with what was still, ultimately, a personal decision, there inevitably came criticism of her choice.

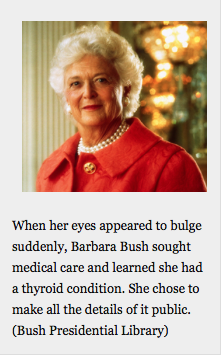

In 1989, Barbara Bush followed the precedent set by Betty Ford and Nancy Reagan, permitting full public disclosure of her diagnosis of Grave’s Disease, a hyperactive thyroid condition, following her detection that her eyesight was changing and that her eyes appeared to bulge.

In 1989, Barbara Bush followed the precedent set by Betty Ford and Nancy Reagan, permitting full public disclosure of her diagnosis of Grave’s Disease, a hyperactive thyroid condition, following her detection that her eyesight was changing and that her eyes appeared to bulge.

Her doing so helped raise public awareness of this condition which often went undetected and led to other complications.

Modernity, interestingly, is not a factor in how fully a First Lady might chose to publicly disclose her health issues.

Nearly twenty years after Barbara Bush chose to disclose her thyroid condition, however, her daughter-in-law Laura Bush did not permit the news that she had a squamous cell carcinoma tumor, commonly known as “skin cancer,” removed from her right shin in November 2006 until five weeks after the surgery.

Nearly twenty years after Barbara Bush chose to disclose her thyroid condition, however, her daughter-in-law Laura Bush did not permit the news that she had a squamous cell carcinoma tumor, commonly known as “skin cancer,” removed from her right shin in November 2006 until five weeks after the surgery.

“It’s no big deal,” she said, explaining her decision, “and we knew it was no big deal at the time.”

No matter how many examples may have been set before her, history shows that when it comes to disclosing their health issues, First Ladies will do as they usually do on matters involving their public lives: what is right for them and not what was right for those before them.

THIS ARTICLE IS THE SOLE COPYRIGHTED PROPERTY OF CARLANTHONYONLINE.COM AND MAY NOT BE REPRINTED IN WHOLE OR PART WITHOUT EXPLICIT WRITTEN PERMISSION.

Categories: First Ladies

Tags: Barbara Bush, Betty Ford, Florence Harding, Jacqueline Kennedy, Laura Bush, Mamie Eisenhower, Melania Trump, Nancy Reagan

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders

Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  “Yes, I am a Liberal,” Barbara Bush’s Politics: Gays, Guns & Equal Rights

“Yes, I am a Liberal,” Barbara Bush’s Politics: Gays, Guns & Equal Rights  Barbara Bush, Early 90s Icon: The Simpsons to The Laptop

Barbara Bush, Early 90s Icon: The Simpsons to The Laptop

Leave a Reply