Melania Trump making a Michigan school visit as part of her anti-bullying effort. (Getty)

On civil rights to gun control to women’s rights, Jackie Kennedy, Pat Nixon, Eleanor Roosevelt, Nancy Reagan give context to the recent declaration that Melania Trump is “Independent” from the President

Copyrighted, 2017

All media and individuals using this original research material or images must both properly credit and link to the website; no written text can be used without permission

First Ladies tend to be subtle in what they say and how they say it. And if these unelected, constitutionally-unempowered presidential spouses hope to be effective, they have to be.

Melania Trump watches her husband react during the campaign.

Still, in the wake of First Lady Melania Trump’s first solo trip focused on childhood bullying, to a Michigan middle school last week, there’s no mistaking the intent of her communications director Stephanie Grisham’s statement to CNN:

“Mrs. Trump is independent and acts independently from her husband. She does what she feels is right, and knows that she has a real opportunity through her role as first lady to have a positive impact on the lives of children.”

Mrs. Trump speaking on bullying at the UN.

As it did a year ago when she first declared that cyber-bullying would be a focus of her tenure as First Lady, the most immediate reaction was how she would reconcile her message with the dramatic conflict exemplified by her husband’s tweeting of belittling nicknames for public figures who disagree with him and hostile reaction to legitimate presidential criticism.

What’s clear is that she doesn’t reconcile it, nor intend to. At one point in the early days of the 2016 campaign, Melania Trump did admit that she advised him to temper the tweeting but also pointed out that he is who he is, and responsible for the reaction he gets.

In an aside during a different media interview, she also confessed that she sometimes thinks she has two boys at home, her son and her husband.

Melania Trump in her home before the 2016 campaign.

Now, she’s made clear that she is who she is, following the advice that she succinctly urged the Michigan students to do: “Be yourself.”

And if he does what he wants, she’s cautiously proving that she does likewise, certainly on social media.

“A White House official told CNN that when it comes to social media, Twitter in particular, the first lady does not check in with her husband before posting. She is her own person,” reported Katie Bennett of CNN in August, “operating the account herself and paying close attention to which events warrant comment and which do not.”

While he speaks for himself, Mrs. Trump’s office has made it explicitly clear that she speaks for herself.

As part of her statement last week, the First Lady’s communications director further stated:

“Her only focus is to effect change within our next generation.”When it comes to children, emotional intelligence is certainly always going to be on her radar. Teaching children the values of empathy and communication, which are at the core of kindness, integrity and leadership, will lead to a future generation of happy, healthy and morally responsible adults.”

Among the more subtle differences between the couple has been the First Lady’s glowing admiration for her predecessor and continuing to maintain Michelle Obama’s vegetable gardens (some wags say she emulated her too much so, referencing her convention speech which lifted portions of her predecessor’s convention speech).

First Lady Michelle Obama meets with Melania Trump for tea in the Yellow Oval Room of the White House, Nov. 10, 2016. (Official White House Photo by Chuck Kennedy)

In contrast, her husband has seemingly sought to deconstruct all of Michelle Obama’s husband’s legacy.

Still, some see the recent “independent” statement as but another small step in a series of words and deeds that Melania Trump has made to help establish a media persona on her own term, strictly apart from the man to whom she is married. Others feel that is a premature conclusion.

While history shows that the derivative power of all First Ladies can never be perceived entirely apart from their husband-Presidents, they do possess the potential to gradually but consistently define their own public identity.

Behind the scenes, even those not cast as “political” developed and held to their own opinions even if it conflicted with the policies and statements of the President.

John and Abigail Adams: at war over war.

In the 1790s, Abigail Adams had insisted that her husband declare war on France: he refused to, knowing it would weaken the new republic.

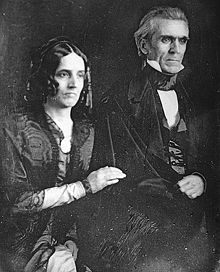

Sarah and James Polk conflicted on banking.

In the 1840s, Sarah Polk pointedly argued the value of a national banking system but President Polk, steeped in old-school Jacksonianism refused to agree.

As family correspondence proved, in 1856 Jane Pierce stood in solidarity with her wide and powerful family of influential New England abolitionists against her husband’s support of slavery expansion into Kansas and other new territories.

Jane Pierce disagreed with her husband’s permitting the spread of slavery.

Sometimes the conflict involved personal concern for a husband that crossed into tactical politics.

Louisa Adams wanted her husband to win his 1828 election campaign and badgered him to defy convention and more aggressively curry favor with influential electors. He considered that beneath him. He lost.

In 1899, the McKinleys disagreed on 1900.

Julia Grant pushed her husband to shatter precedence and seek a third term in 1880 until he officially announced he would not; she did so because she wanted the glory and power to continue.

All through 1899, Ida McKinley argued with her husband to not run again in 1900; her concern was that he’d become yet one more victim to the growing threat of anarchist assassinations of world leaders. He defied her and was assassinated six months into his second term.

Florence Harding made the case against her husband’s intended proposal of a one-term six-year presidency: she won that round.

The Hardings: no one term for him, said she.

She viewed such a proposal as potentially draining his executive powers against the calendar of House and Senate election cycles.

She was less successful in her opposition to the Christmas Day 1921 commuting of socialist Eugene Debs, who had been imprisoned in April of 1919 upon being sentenced for ten years on charges of treason when he encouraged young men to resist the government draft for military service during World War I.

Although President Harding had allowed the First Lady to chose which prisoners in federal penitentiaries would receive pardons and commutations, she was adamant in making her case against Debs.

She believed it would be a sign of overt disrespect to those American servicemen who had been killed or left maimed and disabled during the war, the subjects of her advocacy work as First Lady.

Debs exiting the entrance to the West Wing reception room where after meeting with the President. The First Lady had refused to permit her husband from welcoming the socialist in the residence.

The President, however, felt Debs did not deserve the degree of punishment he received and even said he had “much personal charm and impressive personality.”

The disagreement between Warren and Florence Harding was thus already inflamed on Christmas morning, their physician admitting to a visiting Charles Forbes, head of the newly created veterans Bureau, “They had quite a row this morning.”

Adding fuel to the fire, President Harding invited Debs to come to the White House, so he could shake his hand. Mrs. Harding was furious and refused to let him do so upstairs in the presidential family’s private quarters.

So, instead, on Christmas morning, the President went down to the Oval Office, and there he welcomed Debs alone for a half hour of conversation.

Of course, the press and public never learned of these earlier disagreements during these presidencies, given the societal propriety still maintained about women’s private lives, even those who happened to be married to Presidents.

It was only with the revelations in the written histories of their husbands’ presidencies, publication of their private correspondence or memoirs of staff members that the truth was told, usually well after the women had died.

By the middle of the 20th century, as the public role of women increased in American political life, the views and intentions of First Ladies began publicly emerging more often.

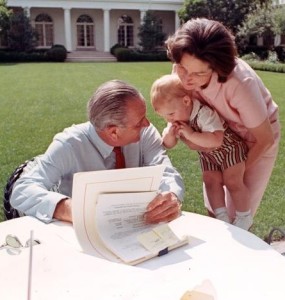

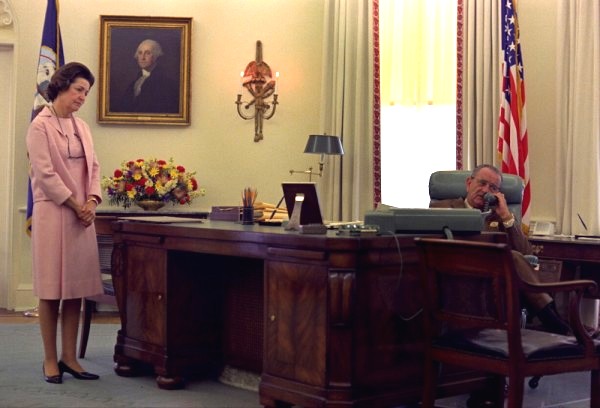

Lady Bird Johnson brings her grandson Lyn over to the President while he works on a speech outside the Oval Office.

While campaigning on behalf of her husband’s 1972 re-election campaign, Pat Nixon stated her belief that some cases of those who had dodged being drafted into the Vietnam War should be considered for amnesty: it was a direct contradiction of her husband’s policies.

During his 1964 presidential election, one of President Lyndon Johnson’s most trusted but overworked aides, the married Walter Jenkins, was arrested for soliciting another man in the YMCA. LBJ learned of the incident while in New York, about to give a speech. His wife, Lady Bird, called about it, and their talk was recorded.

In response to Jenkins immediately resigning his White House job, the First Lady declared her intention to have him hired at one of the family’s television stations back “I wouldn’t do anything along that line now,” he says, cutting her off.

The LBJs.

Without morally condemning Jenkins but focusing instead on what she considered the duress under which he made his indiscreet decision, she snaps back to her husband: “I don’t think that’s right.”

Then she suggests what she will say as a sign of personal support to him. “I wouldn’t say anything…I wouldn’t be available for anything…it’s not something for you to get involved in now. We’re trying to work that out with the best minds we have working on it…Don’t create any more problems that I’ve got.”

He suggests she seek approval first of his aides. She already has.

He’s startled, coming back again saying that if she issued a statement, “Then you confirm it. You approve it, you part of it…you just can’t do that to the presidency, honey.”

Lady Bird Johnson visiting her beleaguered husband in the Oval Office.

She affirms her position: “I’ll try to be discreet but it is my strong feeling that a gesture of support to Walter on our part is best..”

He comes back at her again: “Your average farmer just can’t understand your knowing and approving it, or condoning it…”

Jenkins, far left, a loyal and long time aide to the LBJs.

Mrs. Johnson listened patiently, gathered her thoughts and then declared that she was going to make a statement and released it without the President’s blessing.

Mrs. Johnson reacted in 1964, not unlike Melania Trump did in using Twitter to issue her own statements before her husband on the October 31 New York and August Charlottesville violence without getting into the controversies of them being acts of Islamist or white nationalist terror, but rather focusing on those harmed and the need for freedom of expression without violence.

In her case, Lady Bird Johnson deftly avoided opening a sensitive public debate on homosexuality to instead express a tolerant empathy for “someone who has reached the end point of exhaustion in dedicated service to his country.

Here is the audio tape recording of their battle over the matter:

First Lady Nancy Reagan and President Reagan’s later Chief of Staff Don Regan.

Accounts of First Ladies who substantially disagreed with their husbands on Administration policy or social issues is far briefer than the rich and nuanced history of their influence, which was often strong enough to change a President’s thinking, and public initiatives.

Nancy Reagan famously managed to finally convince her husband to fire his Chief of Staff Donald Regan who, she argued, mishandled the Iran-Contra scandal and the president’s implication in it.

While the President was still deciding whether to oust Regan, the First Lady had her opinion widely leaked without ever backing down. Ronald Reagan finally did what his wife had been publicly urging.

Mamie and McCarthy.

It was known among her closest confidantes that upon her only meeting with him during a 1952 campaign rally, Mamie Eisenhower mistrusted unctuous Senator Joseph McCarthy because of his controversial red-baiting Senate hearings.

It’s unclear whether her refusal to invite him to formal dinners held in honor of the entire Senate in two consecutive years was a decision she had to convince the President of, or whether he asked her to take responsibility for doing so as a subtle way of distancing himself from his fellow Republican.

Dick Cheney and Laura Bush.

However, it is known that the First Lady held final veto power over even the President on who was invited to formal White House dinners and her office issued a statement affirming that it was her decision.

In 2008, before George W. Bush made a decision on a proposed law to prohibit exploration and exploitation by oil and gas interests of the deep ocean shelves of the Pacific rim, the First Lady made clear her own opposition to it with a firm public statement.

In doing so, Laura Bush willingly stood in direction opposition to Vice President Dick Cheney.

Distracted by covering the final days of the 2008 election, the media paid scant attention to the fact that the President chose to follow the advice of the First Lady over the Vice President.

In the latter 20th century, several projects or social issues given undertaken by First Ladies would often, over the course of an administration, come to dovetail with presidential legislative initiative and even help define his legacy.

Jackie Kennedy was snapped having a private word with her husband, detaining him at a state dinner in the hallway.

But initially, many were not enthusiastically supported by the Presidents.

While President Kennedy did not refuse to “let” his wife conduct her historical White House refurnishing, but he did not encourage it, fearing the public might perceive it as an elitist venture; only once it seemed popular with the public did he become greatly supportive.

Lady Bird Johnson’s “beautification” would eventually come to encompass the landmark environmental protection legislation later initiated by her husband.

During her husband’s 1976 campaign, Rosalynn Carter had made speeches promising not just what Jimmy would do as President, but what she would do as First Lady.

In her case, it was nothing less than the most sweeping mental health care reform in over decades.

Rosalynn Carter working as “honorary” chair of her mental health commission.

Mrs. Carter shepherded her effort through each stag with a passion, starting with her getting her husband to create a presidential commission.

When the President informed her that she couldn’t serve as commission chair, she decided she would be a highly directorial “honorary chair.” It wasn’t that Jimmy Carter was reluctant to have his First Lady take the lead on turning her project into federal legislation, only that he had domestic legislation priorities of his own.

Betty Ford with CBS reporter Morley Safer in the 1975 interview in which she made her views on abortion, marijuana and pre-marital sex known.

Not even her husband’s agenda, however, could deter her. She discovered that the reluctance was being directed from his Health, Education and Welfare Secretary Joseph Califano.

When she asked the President to prompt Califano to provide real support to help get her legislation passed, she was greatly disappointed in the result.

And, when Califano was suddenly fired, Mrs. Carter made no secret that “we” had pushed for it.

Betty Ford’s support for the Equal Rights Amendment eventually led to her husband’s declared support of it. In her case, his support wasn’t a prerequisite for hers.

When she let it out during a nationally televised interview, however, that she wasn’t adamantly against marijuana use or pre-marital sex and supported the Supreme Court decision upholding the right to abortion, she was voicing opinions not held by her husband.

It didn’t stop Betty Ford from stating her honest views. As she asked rhetorically in a 1975 speech, “Why should my husband’s job – or yours – prevent us from having our own opinions?”

Barbara Bush called for gun control with first speaking to her husband.

More common are examples of First Ladies holding views independent of their husband and in seeming conflict with policy that are revealed not through prepared statements but their impromptu answers during interviews or media leaks.

Barbara Bush casually conversed during the course of a reporter round-table and offered support of gun control despite her husband’s opposition to it. She later regretted voicing her independent opinion – but did not regret her opinion.

The Clintons were united on healthcare reform, less so on welfare reform.

As Bill Clinton’s welfare reform legislation was being prepared, there were leaks reporting Hillary Clinton’s contention that it didn’t include enough of a safety net for those who fell outside the parameters being outlined for potential recipients.

George W. Bush blocked stem cell research and opposed legal abortion; without seeking to make headlines, Laura Bush presented her own views in the course of nuanced media interviews but ultimately disagreed with him.

Laura and George Bush have a word.

Political analysts often read these contradictions as part of a cynical White House media strategy to consciously disseminate a dissonant voice that is sympathetic to opposition forces, the belief being that having a First Lady speaking for the opposition will somehow mitigate the perception of hard policy and harsh presidency.

It’s an interpretation that seemed confirmed by George W. Bush’s frequent remark that, “Good people can disagree” on abortion.

It was most definitely confirmed by Eleanor Roosevelt herself.

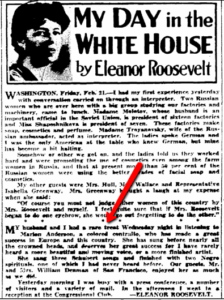

One of the First Lady’s daily newspaper columns.

After her husband’s death she admitted that there were occasions when she would pen one of her daily “My Day” newspaper columns and include in it an idea or opinion that she presented as her own but which was one that she really shared with Franklin.

Although it was usually an issue the President hadn’t yet addressed, he didn’t hesitate in using her column as a “trial balloon” for his ideas.

While on the face of it a comparison between Melania Trump and Eleanor Roosevelt might seem far-fetched, when one examines those First Ladies who most frequently used the modern media of her day to issue her own opinions and statements entirely independent of the President, none did so more often than Mrs. Roosevelt.

Eleanor Roosevelt spoke to the nation weekly, on Sunday evenings.

Whether she was using her daily column, weekly radio show, monthly magazine question-and-answer pieces, or national lecture tours, Eleanor Roosevelt offered opinions that were not always entirely in line with her husband’s on any number of smaller issues, mostly on finer points of legislation involving industry and labor unions.

It rarely troubled the President. “It’s a free country lady,” he often quipped, “I can take care of myself!”

If ever there was a First Lady who made clear that she spoke and acted independently of a President it was Eleanor Roosevelt.

Eleanor Roosevelt kept herself fully informed on all of the decisions facing the President and never hesitated to offer her independent opinions, if not always in public.

On the larger conflicts that required complex strategic approaches by the machiavellian FDR was politically pragmatic. Therein lay Eleanor’s vigorous opposition to him; he might willfully ignore the consequences for sake of expediency, while she refused to overlook the humane aspects of such decisions, and refused to condone them. Her sense of morality guided even those argument she knew she would lose with the President.

Sometimes, she spoke and acted in open conflict with the President, as in her public lobbying for anti-lynching laws which he ignored in order to retain necessary votes for Great Depression support from southern Democrats.

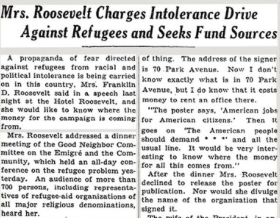

During World War II, she was unrelenting in bringing reports she received about the Holocaust to him, imploring the President to support a widening of the limited refugee policy and order bombings on the Nazi railroads that transported Jews to their death at concentration camps. Acting independently of the President, she wrote and spoke in vigorous public support of a pending congressional bill intended to permit more German Jews into the country.

A news article reporting on Eleanor Roosevelt’s Jewish refugee advocacy.

Failing to do so, she acted on her own in pursing every private avenue possible to help. For his part, acting when he could without the need for congressional approval, FDR did open some legal avenues to allow more Jews into the U.S., though it was a relatively small amount.

Edward Bernard Glick, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Temple University published the article, “Eleanor Roosevelt Talks about Her Husband and the Holocaust,” for the March 22, 2013 issue of American Thinker about his 1958 conversation with her. Some of what she told him:

“Ever since I learned of Hitler’s systematic murder of the Jews, I pressed my husband to bomb the railroad tracks . …I constantly raised the matter with the President….My husband’s answer was always the same:

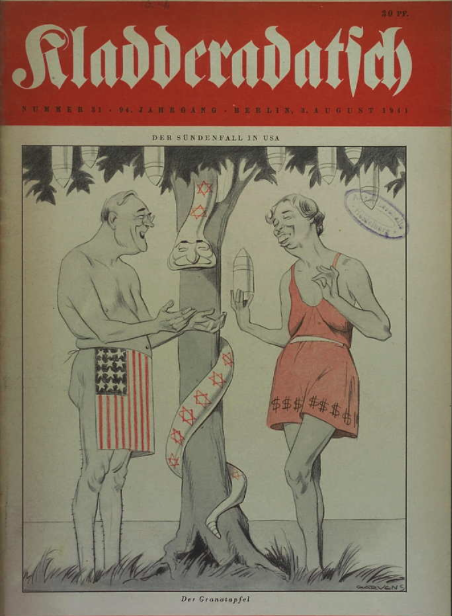

Along with her husband, Eleanor Roosevelt was herself often demeaned in Nazi cartoons.

‘Later….Winning the war comes first, of course, and bombing those railroad tracks are not a top air force priority.

But the war is not the only thing on my mind. I also have to deal with domestic affairs. To get things done, I must have the support of the committee chairmen in the Senate and the House…many of them are anti-Semites…they don’t want any more of them let into this country.

That’s the reason I haven’t pushed for the admission of larger numbers of [refugee] Jews….

I promise you, Eleanor…that when…the legislation that I want and need [is passed], and the war is closer to a victorious end, I shall order the bombing of those railway tracks.

You have my word on it.”

In Germany, Eleanor Roosevelt visited with Jews who survived the Holocaust in February 1946, ten months after her husband’s death.

The Roosevelts had come to the White House just five weeks after Hitler had become chancellor of Germany. President Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, just two weeks before Hitler died on April 30, 1945. Of course, by then the systemic mass murder of Jews had been completed.

Ten months later, in February of 1946, the widowed Mrs. Roosevelt went by herself to the Zeilsheim, Germany camp for displaced persons, many of them being Jewish survivors of the concentration camps. By then a representative of the newly-formed United Nations, she dedicated the rest of her life to the issues facing refugees and supported the state of Israel as a homeland for them.

Mrs. Roosevelt at Gila River, Arizona at a Japanese-American Internment Center.

Similarly, she was enraged at FDR calling for the internment of Japanese-Americans.

While she relented when he asked her to not publicly declare hers opposition to this, the First Lady did not ask his permission before making numerous visits to the camps and offering what little aid and support she could.

And occasionally, Eleanor Roosevelt took the middle ground. Despite evidence of communist membership among the American Students Union, she arranged for the President to address the group. When members showed disrespect to him, however, she defended her husband.

Rarely does one find examples of First Ladies making statements, responding to questions or initiating actions that don’t reflect their genuine opinions. Frequently, they represent more empathetic perspectives on ignored and powerless constituencies and when they have assumed a muted public response, their relative silence on important issues seems to be a matter of political pressure.

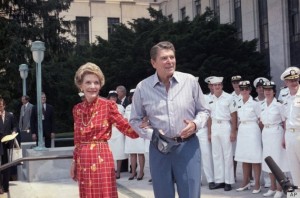

Mrs. Reagan tugs her husband along as he stops to speak with the press.

While Nancy Reagan stated that she often disagreed with her husband’s decisions she also made clear that they made an effort to keep this from the public, fearful of generating media coverage of marital disagreements and distracting attention from the President’s agenda.

However, if it meant letting her views known before he had determined or let his be known, Nancy Reagan could move swiftly – even if it conflicted with members of his Administration and party.

Clockwise, from upper left: Bauer, Reagan, Lilly, Humphrey, Schafly.

The First Lady had been pressing her husband to create a presidential AIDS commission well before he did, late into the crisis and sought out Dr, Frank Lilly, an openly-gay doctor be named to it, the first such individual ever appointed by a President. She had identified him with the help of her stepbrother, a fellow Philadelphia physician.

In doing so, Mrs. Reagan defied the specific admonishments of Gary Bauer, Reagan’s chief domestic policy advisor, and Gordon Humphrey, Republican of New Hampshire, who said that doing so would be “sending the message to society – especially to impressionable youth – that homosexuality is simply an alternative lifestyle.”

She also took issue with the advocacy of conservative leader Phyllis Schafly, who urged that there be mandatory testing of all gay people and possibly quarantining; the First Lady did so not through a White House statement but by giving her son Ron, an AIDS education advocate, permission to make her views publicly known.

Nancy Reagan, seen here with her son Ron after one of his ballet performances, shared many political views on social issues with him.

While the President never issued a statement to allay public ignorance on methods of transmission, the First Lady did, following her own interaction with makeup artist Way Bandy who died of AIDS in 1988.

Though it is true that Mrs. Reagan had enormous influence over her husband and also true that Ronald Reagan’s delay in addressing AIDS left a vacuum of vital leadership at a juncture when the numbers who died of it might have been stemmed, she was not ultimately responsible for the politically-expedient failure to do so.

The Obamas cross the South Lawn.

At best, it is naively optimistic to suggest a First Lady has such omnipotent power that she can predict which small issues will mushroom into great crises, then force the President to see things her way and follow her orders to take action.

Yes, there have been a few examples of this, but such scenarios resulted not just from one problem, but the convergence of numerous unforeseen factors that not even the most prescient of First Lady astrologers could have helped.

It would be equally unfair and irrational to hold Eleanor Roosevelt responsible for failing to make Franklin prevent the Holocaust as it would be to blame Pat Nixon for failing to make Dick withdraw troops from Vietnam or Michelle Obama for failing to make Barack intervene in the Syrian conflict before it conflated.

First Ladies may not publicly state everything they really think but by and large, they speak the truth far more often than do Presidents.

Nellie Taft exchanging a smiling glance at her husband.

While her husband was still campaigning for the presidency, for example, Nellie Taft declared herself in support of women’s suffrage on the condition that before being permitted to vote that both women and men first qualify, required to pass an exam on the process of government and the electoral system, proving they were informed and understood their right.

She maintained her unpopular but principled opinion throughout her husband’s presidency, after it ended and even after 1920 when suffrage was granted.

The Tafts.

In contrast, her husband declared that he opposed women’s suffrage during his presidential campaign, taking a stand supported by a majority of voters. While he was president and then seeking a second term, he began to more frequently suggest he could support it. Taft only finally supported a woman’s right to vote after losing re-election and no longer had anything to risk.

Later, when Taft was made Chief Justice, he and Nellie Taft more contentiously bickered over the constitutionality of prohibition. But the wife of the highest judicial figure in the nation refused to give up her right to drink, infuriating him as she blithely indulged her love of beer.

The taint of sexism can be easily read into all this, that by their own strong opinions not influencing what their husbands say in statements or sign into policy, wives are ultimately secondary or submissive figures in a presidency.

Theodore and Edith Roosevelt.

Few Presidents were so tyrannical that they ignored or shut out the views of their spouses but there are “sexist” examples of some who adhered to a male-dominant worldview.

Upon his 1904 re-election, Theodore Roosevelt rushed to declare he would not run again, failing to first consult his wife Edith’s strong opinion that it essentially made him a lame-duck earlier than necessary.

The Coolidges enjoy some ice cream and cake.

When Grace Coolidge requested foreknowledge of the President’s daily schedule of meetings and appointments, he snapped back that such information was not freely divulged and she wasn’t privileged to it.

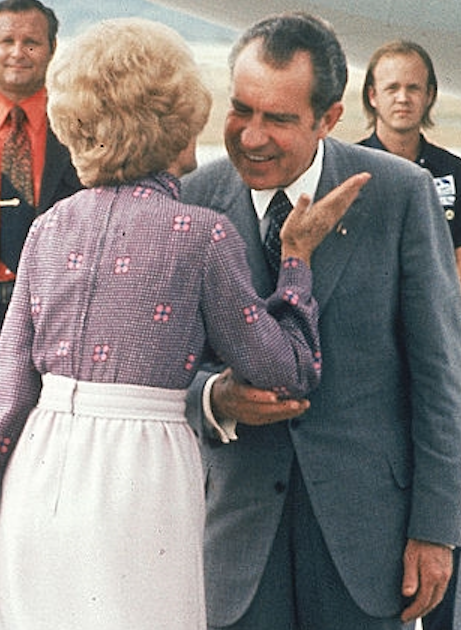

First learning about her husband’s secret tape-recording system in 1973 from public news reports, Pat Nixon made the case to him that he should destroy the tapes while they were still legally considered private property, and before they could be potentially subpoenaed.

The Nixons at the Kennedy Center.

By ignoring her advice, Richard Nixon did nothing less than begin the descent that led to his resignation.

Nixon defied his First Lady less overtly, however, after she made a 1971 public declaration that, following two Supreme Court openings, she would insist that he appoint the first woman to the bench.

Her declaration caught the press by surprise, a rare spontaneous quip she uttered in reply to a reporter’s question while accompanying him to the opening of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

As urged by his wife, the President went through the motions of soliciting recommendations of viable women judges and seemingly gave them consideration.

Pat Nixon delivering public remarks.

Pat Nixon did not forget her promise, soon after granting a magazine interview in which she affirmed, “Our population is more than fifty percent women, so why not? A woman will help to balance the Court.”

A month later, she again raised the issue on her own with the press, unprompted.

Three days later, October 21, 1971, President Nixon announced his nominations of Lewis Powell and William Renquist to the court.

Pat Nixon offers a whisper to Richard Nixon at a Florida airport in October 1972.

A tense scene ensued that night at the family dinner table, their daughter Julie recalling her mother being “annoyed” that her public promise had “gone unheeded.” She again argued her point until “wearily” the President cut her off: “We tried to do the best we could, Pat.”

Unknown to her, however, Nixon was intending to exploit her independence to his advantage, telling an aide to spread a media story that the First Lady and their daughters were the “strongest advocates” for a woman justice; even if he did not chose a woman for the Supreme Court, he believed that he would get credit for at least sympathizing with the women’s movement for equality.

Nixon was pleased with the way the news was taken, “except for my wife, but boy is she mad.”

His taped call with the Attorney General revealed his actual lack of enthusiasm:

While Pat Nixon was spared ever being able to hear the tape of her husband’s true feelings, Jackie Kennedy was spared ever being credited for a small but courageous act of resistance against her husband.

Clarence Ferguson, counsel to the Civil Rights Commission and his wife are greeted by the President and Mrs. Kennedy at their 1963 Lincoln Day reception.

It was all the more ironic given her own efforts to burnish his record as a civil rights leader who acted above politics.

African-American leaders, growing increasingly frustrated with President John F. Kennedy’s delay in pushing for a full civil rights bill, pressed in on him as 1963 began.

His immediate response was to host a Lincoln Day reception for a thousand prominent African-American leaders and their spouses, to commemorate the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. The event was organized by Louis Martin, the only African-American executive of the National Democratic Committee.

At the last minute, guests were contacted with instructions to use not the traditional east gate for entrance to the event, but rather the southwest gate.

Davis and Britt.

The reason given by the President was that he wished to greet them in the family quarters; the truth was that he feared the reaction of southerner segregationist congressional leaders to his hosting the largest White House gathering in presidential history for people of color. One way to avoid this was to prevent the reporters waiting to observe and write about guests at the east gate from getting a sense of the event’s enormity. Only White House photographers would be recording the guests on the state floor.

The President’s political sensitivity extended to the presence of one particular guest, entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. who attended with his wife, the actress May Britt, who was white. More than anything he wanted to prevent the inter-racial couple from being photographed together, knowing it would set off a firestorm among Americans in the eleven states where inter-racial marriage was still illegal.

As the reception was beginning on the state floor, the President saw the entertainer’s name on the guest list while still upstairs with Jackie. He told several aides repeatedly, “Get them out of here!” When Davis had sung the Star Spangled Banner during one day of the convention that nominated JFK in July 1960, he had been booed among the southern delegations. Kennedy had thus blocked Davis from performing at his Inaugural Gala in January of 1961.

Jackie Kennedy finally agreed to pose with her husband and the LBJs after refusing to be used in JFK’s effort to separate Sammy Davis Jr. from his white wife May Britt.

Then the President came up with another idea: have the First Lady engage and distract May Britt in conversation, and keep her apart from her husband . Initially, he ordered an assistant to so instruct Jackie.

As historian Richard Reeves recorded, “Jacqueline Kennedy refused. She was so angry at the suggestion she did not want to go downstairs at all.”

Appalled at the idea of such a cynical move, the President’s wife stood her ground while he kept pleading with her to join him, without further delaying their presence at the reception, which was by then in full swing..

Jacqueline Kennedy circulating at the Lincoln Day reception before joining a small group for a photograph.

She finally relented to circulate through there state floor, then sit for a group photograph in the Diplomatic Reception Room on the ground floor, along with her husband, Vice President and Mrs. Johnson and her sister-in-law, the Attorney-General’s wife, and several prominent African-Americans and their spouses.

“Then,” Reeves further chronicled, “she stood up, said she did not feel well, and left in tears.”

In 1966, Sammy Davis Jr. photographed his wife May Britt with Jackie Kennedy.

Jackie Kennedy, however, did not do as her husband wished, making no effort to detain May Britt. Instead, neither Davis nor Britt were invited to join in the VIP photograph that was released to the press. In fact, the President’s caution had been so great that there was relatively no press about the historic event anywhere in the nation’s newspapers over the next few days.

There was a curious post-script to the incident. During a private gathering organized for then-U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, Sammy Davis, Jr. and May Britt had the chance to socialize privately with Jackie Kennedy. By then, she had been widowed three years.

And Sammy Davis, Jr. pulled out his camera and snapped some pictures of her and the other guests, including one of his wife and the president’s widow.

The public may believe the perception advanced in campaigns by candidates that they are electing a marital “team,” but in the presidency there is only one person with the authority to make decisions by which history will judge them.

Consider the first married woman elected to the presidency: no matter how dominant a male culture may still persist at that time or how influential her husband might be, only the first “lady president” will have the right to exercise presidential powers and ultimately be held responsible for doing so.

Melania Trump listens tentatively as her husband takes the mike.

Based on what little is known about the new First Lady’s role within her husband’s presidency, it seems likely that the issues with which she may substantially disagree with him will be more about the style in which he publicly presents himself and his decisions and policies, rather than on the formation of legislation and budgets.

Her reported scorn for his decision to hire Anthony Scaramucci in July of 2017 as a chief of staff, after the latter frequently cursed in a print interview and her reportedly registering her opinion that he immediately be fired, would exemplify this.

If so, she would be more like most of her predecessors.

Eliza Johnson’s firm but silent touching of her husband’s arms was enough to cool him down.

Eliza Johnson was known to shut up her raging husband during his 1868 impeachment trial and admonish him to keep his cool in public, by silently pressing her two hands against his arms.

During her husband’s second term, from 1893 to 1897, when the nation saw a radical increase in immigration and tensions among ethnic groups vying for work, Frances Cleveland ensured that he never wore lapel pins or flowers, or clothes in colors that were known symbols identified with any one particular demographic, helping him avoid any unwitting suggestion he supported one group over another.

Bess Truman making small talk with a Senate wife and a Cabinet wife. (Life)

Perhaps Melania Trump can best relate to a particular First Lady she’s already shown a resemblance to by making her own decisions without regard to media reaction, one known as the “independent lady of Independence,” Bess Truman.

On one occasions, while Mrs. Truman stood with a friend listening to Harry Truman go off-script and make heated remarks about the horse “manure” being shoveled at him by the opposition, the woman expressed to the First Lady her shock at hearing the President of the United States use such an undignified word.

“It’s taken me a long time to get him to use that word instead,” replied Mrs. Truman.

Categories: First Families, First Ladies, The Trumps

Tags: Abigail Adams, Eleanor Roosevelt, Florence Harding, Hillary Clinton, Jacqueline Kennedy, Melania Trump, Nancy Reagan

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders

Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders  The President as King: A Political Cartoon History

The President as King: A Political Cartoon History  The First White House Valentine’s Day Dance: the McKinleys, Ragtime, Racism & The Romance of the “Ghost Girls”

The First White House Valentine’s Day Dance: the McKinleys, Ragtime, Racism & The Romance of the “Ghost Girls”  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Thank you Carl for a wonderful fact filled article on these amazing women who have held this position. For example, I knew nothing about Mrs. Harding and Eugene Debs –

Thank you again and I continue to look forward to reading and learning from your blogs.

David

Chicago, IL