In a gown of her signature shade of pale blue, First Lady Ida McKinley presiding at the center of the crowd in the White House State Dining Room at her 1901 Valentine’s Day dance. (original artwork, carlanthonyonline.com)

On February 14, 1901, just over three months after he won re-election to a second term and eighteen days before his second inauguration, President William McKinley and his wife, First Lady Ida McKinley hosted the fourth of the five White House dinners of the so-called “social season.”

The State Dining Room during the 1850s Franklin Pierce presidency.

The dinner was a routine annual event. To honor members of the military, the judiciary, the diplomatic corps, the congress and the cabinet, the President and First Lady hosted these formal dinners from the end of November until Ash Wednesday, the religious day that marked the beginning of the Lenten season in the Christian calendar. (These “official dinners” were sometimes called “state dinners,” although the latter term is now used strictly in reference to those held in honor of visiting foreign leaders).

In February of 1901, the McKinleys would host their last social season dinner the following Tuesday, the night before Lent; for several weeks afterwards, there was a calendar of small “musicale” concerts at the White House and in the homes of elite Washingtonians.

The large Harrison clan watched the Easter Egg Roll festivities from the South Portico.

Formal White House entertaining ended with the children’s egg roll lawn party held on the South Lawn the day after Easter Sunday, First Families hosting exclusive receptions for invited guests on the South Balcony, not unlike a royal family overlooking the children of the hoi-polloi frolic in colored-egg games below.

What made the February 1901 diplomatic dinner unusual was that it was the first time that dancing became part of a White House state dinner and the first time that the walls of the one-century old executive mansion echoed with the new type of music known as “ragtime,” and was also the first known event in White House history held to mark the holiday of love, Valentine’s Day.

The event, however, offered a glimpse of many subtextual forces occurring in American society at the time. It can be further argued that such forces continue now, in different forms.

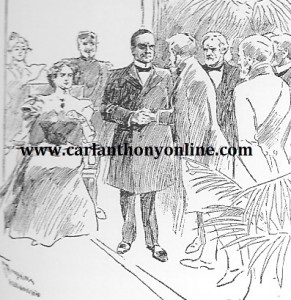

The President and Mrs. McKinley hosting their annual dinner for the diplomatic corps. The space limitations meant that the dining room table had to be set up along the full length of the state floor’s hallway. Mrs. McKinley is seated at left, in a yellow dress, the President beside her in white tie and tails.

To Ida McKinley must go the credit for the modern-day White House official dinner program, with entertainment being provided to guests who, after the meal, were joined by several dozen others invited for the show.

The table set for a McKinley official dinner, in the White House cross hallway.

It came as no surprise to those who knew her well. Whether it was a classical music concert, theatrical performances of drama, comedy and vaudeville, or singers of opera or popular music, this First Lady was passionately devoted to live performances.

Elsie Janis, later a famous actress, credited the McKinleys with launching her career.

Often inviting artists to come visit with her back at the White House after their shows she also collected, framed and displayed their autographed photographs and helped to make the career of at least one woman singer, the young Elsie Janis.

Mrs. McKinley might never appear alongside her pious husband at church on Sunday mornings, but she certainly had no problem appearing at matinees and evening performances later in the day.

Starting with the March 24, 1897 state dinner for the Cabinet, when she had prima donna Ella Russell provide the entertainment after a state dinner, she made music a permanent part of her White House style. That dinner entertainment had Miss Russell, accompanied by violinist Frank Wilczek, sing arias from Listz’s Lorley and, for the President who was of Scotch-Irish ancestry and favored the songs of his ancestral land, the Scottish ballads Robin Adair and Within a Mile of Edinboro Town.

The February 14, 1901 dinner entertainment music was very different; it was specifically intended for dancing.

Ida McKinley received guests seated next to the standing President.

This was also a First Lady who loved to watch people dance and, when she could force herself to muster the energy and master some pain, loved to dance if she could. That was not at all the way she was perceived by the public, however.

At White House events, she typically remained seated in a large blue and gold chair while guests made their way to her and the President on receiving lines. When the general public glimpsed her, she was almost always leaning on a cane and sometimes, struggling to walk independently, depended on the strong arm of an escort.

Mary Barber.

The reality, however, was that for nearly the entire first half of her husband’s presidency, from March of 1897 until June of 1899, Ida McKinley enjoyed strong health without any reports of the dramatic seizures marking the latter part of the presidential years (she did suffer from a mild form of epilepsy) or the flaring of nerve damage that could limit her mobility.

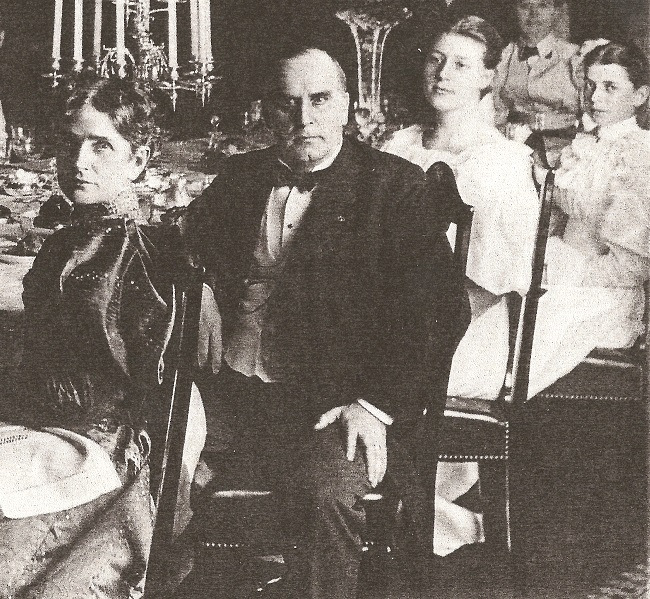

The McKinleys seated at a dinner with her nieces Mary and Ida Barber.

During that period, she had not only hosted an 1897 holiday season dance party in honor of her visiting niece Mary Barber, and even joined in a quadrille and waltz herself.

She had likewise hosted and joined in an 1896 holiday dance party just before leaving her Canton, Ohio home to move into the White House. One newspaper reported on the “graceful ease with which Mrs. McKinley was able to go through the figure” of “an old-fashioned cotillion.”

Ida McKinley in a newspaper illustration which showed her using a wheelchair.

Those dance parties were private, despite the presence of reporters. The national media persisted in depicting the First Lady as a failing invalid, the Victorian lady always on the fainting couch. It was no accident.

In fact, it was the President who saw that public perception of his wife as needy helped elevate his own calculated image as a “saintly martyr” to her every whim.

McKinley speaking from his front porch, Ida McKinley listens at far right.

He used it as an excuse for keeping his campaign based at their Ohio home, rather than make a railroad whistle stop tour and even try to compete with the powerful speaking skills of his opponent William Jennings Bryan.

More menacingly, he naively ensured that she never suffered a seizure at a public event by dangerously increasing the dosage of bromide powders, which deadened her nervous system but came dangerously close to destroying it. In this condition, it left her dazed and listless, unable to respond normally and only furthering the Invalid Ida image.

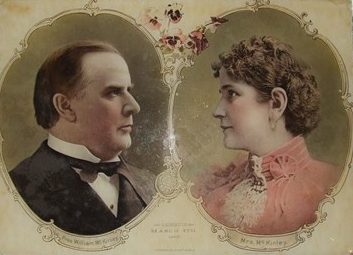

The First Lady never cared about her public image but was obsessive in wanting others to adore her husband as much as she did. Her blind worship of him romanticized his every word and deed. For his part, McKinley spoke about her with rapturous adoration, declaring that all she saw when he looked at her was the timeless young woman with whom he’d first fallen in love.

McKinley’s sacrificial devotion to Ida was a calculated centerpiece of his own carefully crafted public persona – but it was based on his true love for her.

While his ruthless ambition sometimes trumped his devotion to Ida, the President would leave a Cabinet meeting to hold her hand or find her knitting needles. Every day of their entire married life was Valentine’s Day, filled with kisses, hugs, swooning and declaration of Victorian romantic love.

If often a cloying codependency, the McKinley loveliest captured the public’s curiosity and became a permanent part of his political schtick.

While their February 14, 1901 dance was ostensibly just the after-dinner music provided by the Marine Band, which stationed itself in the old greenhouses that adjoined the State Dining Room, the McKinleys wanted to mark Valentine’s Day, intending to spark romance among the young and single guests who they invited just for the dance.

Ida McKinley seated inside the White House greenhouse, which opened into the State Dining Room.

With a cloth “crash” placed over the State Dining Room floor, the music began promptly after dinner, at about eight-thirty that night.

That night’s dance program was divided into two halves, each part representing a distinctively different type of music. There were the romantic waltzes, evoking the grandeur of European capital society, familiar and intended for older adult guests to enjoy.

The other type of dance known as the “two-step,” conducted with the new sound then raging across the nation known as “ragtime,” was a livelier, faster sound especially popular with, and intended to appeal to the younger generation.

The Marine Band, which provided all the music for White House entertainments, was stationed just inside the doors of the mansion’s old greenhouses, which opened into the State Dining Room.The dance pieces for the “two-step” portion opened with a formal promenade, “The Admiral Dewey March” written in 1899 to commemorate the American naval admiral hailed as the hero of President McKinley’s victorious Spanish-American War. The song’s composer was the legendary retired Marine Band conductor John Phillip Sousa, who was ironically the son of a Spanish immigrant.

Crowds cheering on Sousa in a painting by Howard Chandler Christy.

Also played was his 1900 composition “Hail to the Spirit of Liberty March,” hardly the sort of music that lended itself to any kind of dancing, although apparently adapted by Sousa and his band for it.” Another piece, “Lanciers, Foxy Quiller,” was also relatively new music, adapted from a comic opera that had opened on Broadway three months earlier.

Kerry Mills.

Abe Holzmann.

Harry Zickel.

There were four ragtime compositions for the White House Valentine’s Day dance: “Whistling Rufus” written by Kerry Mills in 1899, “Bunch o’ Blackberries” written by Abe Holzmann in 1899, “Goo-Goo Eyes,” written by Hughie Cannon in 1900, and “Black America: March & Two-Step, A Negro Oddity,” written by Harry H. Zickel in 1895.”

Two of these composers would later be incorrectly identified as African-Americans. In fact, all four of them were not only white men, three of whom composed other pieces that were set to overtly racist lyrics and sold as sheet music with racist stereotypic imagery.

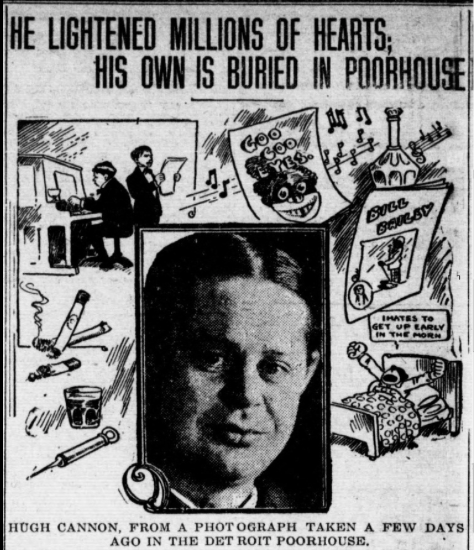

Hugh Cannon’s 1910 Tacoma Times obituary used racist cartoons to reference his ragtime song “Goo Goo Eyes” played at the White House Valentine’s Day dance.

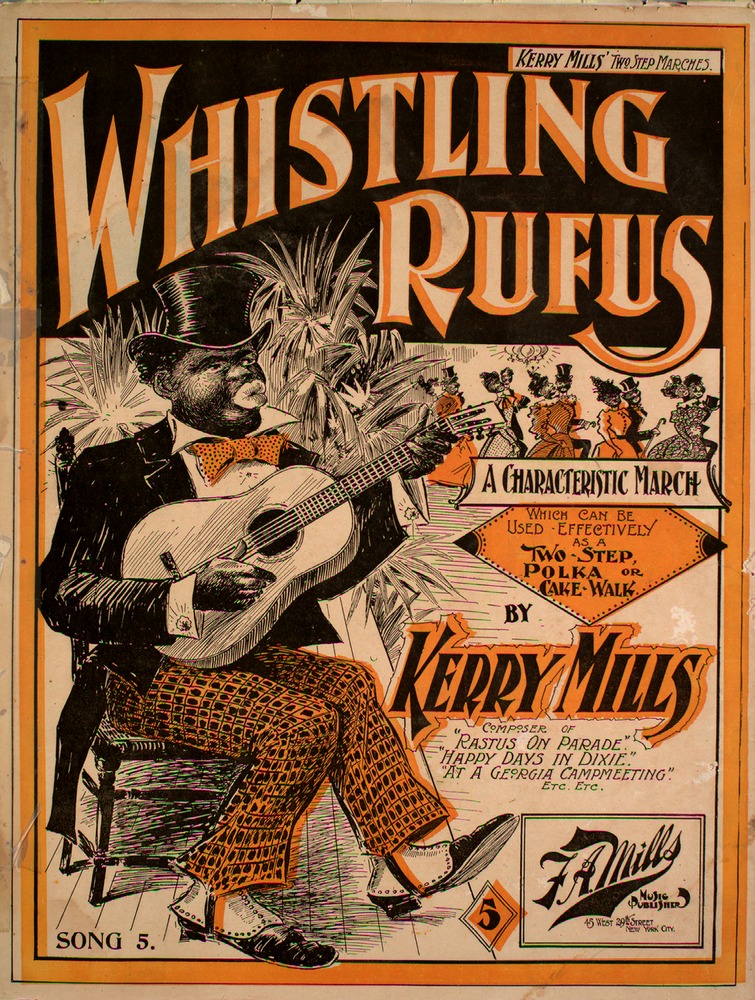

Kerry Mills (“Whistling Rufus”) was a ragtime composer and music publishing executive during the Tin Pan Alley era; athough the art for the sheet music of “Whistling Rufus” reflected the derogatory image of black Americans, there is no suggested he had anything to do with its design or approval. None of his other works reflected ethnic stereotypes. Not so for the other three ragtime composers.

Abe Holzmann (“Bunch o’Blackberries”), son of a Hungarian immigrant, composed a number of racist pieces including “Smokey Moke,” “Alagazam: A Song With Humorous Darky Text,” and “Uncle Sammy.”

Hughie Cannon (“Goo-Goo Eyes”), began his career as an singer dancer and piano player as part of Barlow’s Minstrels in the 1890s. Best known for composing “Won’t You Come Home Bill Bailey” (and “Frankie and Johnnie” Mae West’s Gay 90’s evocation theme song), he also wrote pieces that employed the racist black dialect of minstrel shows, including “For Lawdy Sakes, Feed My Dog,” “I Hates To Get Up Early In The Morning,” and “Possum Pie.”

Among his many compositions, Harry Zickel (“Black America”) also wrote the overtly racist “Belle of Koontucky.”

Here are those four ragtime numbers first played at the White House at the first known Valentine’s Day event hosted in the presidential mansion:

Ragtime was a distinctly African American form of music; it evolved from early black march band music used for dancing a “jig” and “rag,” with distinct syncopated rhythms that originated in Africa. It was also used for a highly animated type of dance known as a “cakewalk.”

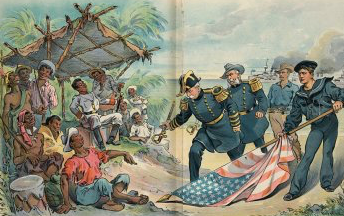

A scene depicting white Americans watching black Americans dance the cakewalk, which had been appropriated from them – and which they would then appropriate in its new form.

The “cakewalk” began when enslaved black people humorously imitated the formal dancing style of their white owners. These owners were fascinated by the adaptation of their own mannerisms and hosted dancing contests for the slaves, the prize of which was cake. Soon enough, white Americans appropriated the black American cakewalk, blending a racial cultural legacy.

It wasn’t long before the “syncopated sound” was set to mocking lyrics, composed with all of the worst racist 19th century stereotypes of African-Americans; these were dubbed “coon songs.”

With a new sound of music, but with sarcastic caricatured lyrics about African-American life, “coon songs” became sensationally popular with Americans both white and black, native and immigrant, some published sheet music selling by the millions. Many composers even took previously published ragtime music and wrote new lyrics with “add[ed] words typical of coon songs.”

One of the “coon songs” performed at the White House Valentine’s Day dance without the offensive lyrics and only the ragtime music.

Starting in 1880 with “The Dandy Coon’s Parade,” these “coon songs” were the rage, hundreds published each year well into the new century. The terminology had begun in reference to the anti-slavery Whig Party’s animal mascot of the raccoon, in the manner of the Democratic donkey and Republican elephant. Thus, those white Americans sympathetic to black-Americans were nicknamed “coons,” with the phrase eventually being applied just to African-Americans.

Coming as it did just as the popular music business exploded across the country, thousands of such songs being generated by “Tin Pan Alley” composers, some academics later suggested that the depiction of black Americans as unruly and dangerous in the lyrics of “coon songs” served as a “mechanism for justifying segregation and subordination.” Food references, gambling, ignorance and dishonesty were elements all derived from the pre-Civil War minstrel show depictions of enslaved people.

The songs reinforced the stereotype of promiscuity with references to a person’s “honey” which meant the person they lived with but didn’t marry, a legacy of slave families being sold apart from each other. Since any new “coon song” practically guaranteed sales, almost all popular songwriters at the time composed its music and lyrics, including Irving Berlin and one of Sousa’s assistants, Arthur Pryor, who supplied them for Sousa to perform. Social critic H. L. Mencken blamed the popularity of the songs and use of the term “coon” in most of the sheet music titles for establishing the derogatory term.

Scott Joplin is best known as a father of ragtime music, but also wrote the lyrics for at least one known “coon song.”

It was a complicated reality, however, for if it was true that white Americans seemed to most enjoy the often grotesque parodies that the songs entailed, many black American composers wrote the music or lyrics and benefitted from the craze, some later making the case that the “coon songs” had opened up their chance to make the rich heritage of African American music a predominant factor in the changing sounds of the nation.

Even the most legendary of African-American ragtime composers, Scott Joplin wrote one. In fact, many of the most successful “coon song” composers were black Americans, including Sam Lucas, Sidney L. Perrin, Bob Cole, George Walker and Bert Williams.

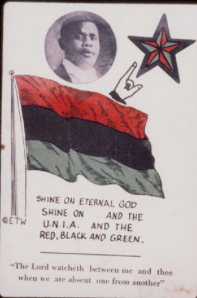

Marcus Garvey, African-American leader and the flag created in 1920 in reaction to a song claiming that black Americans had no flag of their own.

The eventual backlash against the racism did result in some emerging sense of racial pride. In response to the song “Every Race Has a Flag but the Coon,” the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League created a red-black-green flag in 1920.

In spite of the racist damage caused by the “coon songs” they also led to widespread popularization of all black music for all Americans.

The lyrics came to influence the popularity of the blues as a new form of music derived from African-American tradition.

They also helped introduce and make authentic black music appealing to the entire nation. Black “coon song” songwriters and performers became wealthy enough to support their new works developing African-American musical theater, which drew on their authentic experiences and those of their parents and grandparents.

Some African-American composers who found enormous professional and financial success from their “coon songs” later apologized for the harm such songs generated. One, Bob Cole, declared in 1905 that the “day [of writing and profiting from coon songs] has passed with the softly flowing tide of revelations” about the increased racial segregation and violence against black Americans.

Ernest Hogan not only performed in minstrel shows and wrote “coon songs” but was the first African-American to produce and star in a Broadway show.

In 1895, African American composer and performer Ernest Hogan published “All Coons Look Alike to Me” and it broke all records, selling over a million copies of sheet music. While later regretting what he called his “race betrayal” he pointed out that the song helped launch the sound of ragtime around the world:

“(That) song caused a lot of trouble in and out of show business, but it was also good for show business because at the time money was short in all walks of life. With the publication of that song, a new musical rhythm was given to the people. Its popularity grew and it sold like wildfire… That one song opened the way for a lot of colored and white songwriters. Finding the rhythm so great, they stuck to it … and now you get hit songs without the word ‘coon.’ … [Ragtime music] would have been lost to the world if I had not put it on paper…”

How could a President and First Lady permit a performance of music that included “Negro dialect” and lyrics that were sarcastically demeaning of African-Americans, playing on old southern stereotypes?

White American performer Lew Dockstader in 1900 appearing in blackface. Three weeks after becoming President, William McKinley watched a blackface performance by white actor George O’Comnor.

President William McKinley long enjoyed the famous blackface minstrel performances of white comic actor George O’Connor, who performed “Mammy’s Little Alabama Coon” on March 27, 1897 for the President. McKinleys favorite musical number, “Louisiana Lou,” was a famous “coon song” written in 1894.

If the lyrics and sheet music art of the “coon songs” were racist, the mere sound of it to ragtime music was not. In fact, at the White House Valentine’s Day dance all of the ragtime songs were performed without lyrics, the must intended solely for dancing.

None of the offensive words associated with the ragtime songs were heard in the White House.

Trying to cast the early 20th century William and Ida McKinley as racist white supremacists by their permitting to be played in the White House what would have been wordless music then associated with “coon songs” would have left them bewildered and clueless to the more literal and less racist standards of the early 21st century.

Certainly their wealth afforded them the “white privilege” of blindness to just how traumatically affected the entire national population of African Americans was impacted by the increasing rise of lynchings and hangings of black citizens. And yet, by the lower standards of that era, the McKinleys were more progressive – if not always in his polices, then certainly in their personal lives.

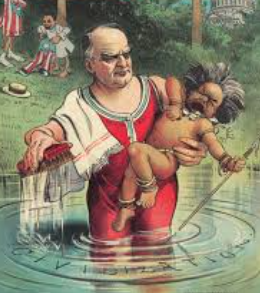

A cartoon of the era satirizing President McKinley’s paternalistic racism towards the mixed-race Filipino people.

By today’s standards, for example, McKinley’s decision to hold the Philippine Islands after the Spanish-American War on the premise that the native people first needed to be “uplifted” before they could be given control of their own nation is seen as the very worst of paternalistic colonialism, a spreading of white American racism towards people of color in other nations.

However, in the context of that era, this view becomes complicated. Those “anti-imperialists” like Mark Twain who opposed McKinley retaining the Philippines are today often held up as being enlightened and seeking to combat the inherent racism in the decision.

Another racist cartoon showing Filipinos staring at Admiral Dewey as he arrived in the Philippines.

In reality, there was a far deeper and darker racism running beneath the thinking of many leading anti-Imperialists: they believed it was not worth the time and money to assume control and responsibility for the Philippines because the Filipinos were racially incapable of ever running their own country.

President McKinley never bought into such thinking. In a presidential era of eugenics, when Theodore Roosevelt judged the intellectual abilities of Asian, African, Native-American, Latin and also European races by their origins and Woodrow Wilson imposed his white supremacist “Jim Crow” segregation on the federal workforce, William McKinley stands apart.

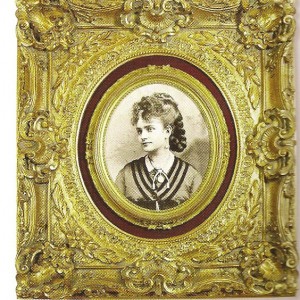

Young Ida Saxton was raised in a rabidly abolitionist family.

Ida McKinley, however, felt even more intensely about eradicating racism, and using education to do so.

She had been inculcated with a radical abolitionist belief by her family; her grandfather’s home had even served as a safe house for escaped enslaved people seeking freedom from slavery in the south, part of the Underground Railroad.

She was educated in grade school and then boarding school by an extraordinary mentor, the Ohio abolitionist and suffragist Betsy Mix Cowles, a colleague of African-American writer Sojourner Truth.

Abolitionist and suffragist Betsy Cowles was the future First Lady’s mentor.

Together with Cowles, young Ida Saxton abandoned the Delphi Academy in upstate New York when they detected the strong support there for slavery.

Through word and deed, First Lady Ida McKinley not only demonstrated her belief in the need for equal access to education of the races – but also the genders.

Ida McKinley sat outside to review Tuskegee Institute’s African American women students in a public parade.

When she decided to underwrite the full college educations of her African-American laundrywoman’s children, she did so on the condition that the woman’s daughters be given the same quality of schooling as the sons.

When she joined the President on a visit to Booker T. Washington’s famous trade school for young black Americans, Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, she toured the separate school for African American women students and then, despite her weakened immune system and susceptibility to colds, sat in frigid temperatures in an open carriage to review them in a public parade.

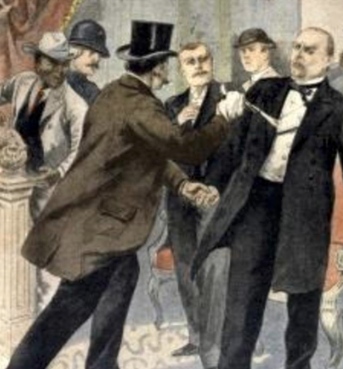

Ben Parker was depicted in many of the first sketches of McKinley’s assassination but his effort to prevent the murder was later expunged from the official record by the Secret Service.

When her husband was shot and killed seven months after their Valentine’s Day dinner, the president’s widow learned that an African-American Ben Parker, waiting on the reception line to shake hands with McKinley was the first to detect the threat posed by Leon Czolgosz, who stood in front of him with a bandaged hand disguising the gun and attempted to stop the assassin

Ben Parker.

The negligent Secret Service expunged the incident from the record but Ida McKinley learned the truth.

She then insisted that the government reward Parker (who had lost his job as a waiter) with a federal job and called on friends to contribute funds to outright purchase a home for the man.

Her most dubious act of political power, however, was her influencing the President to retain the Philippines, a decision viewed with a subtext of racism towards the largely mixed-race population, descended from both Asian and Spanish settlers. The President’s telling a group of Protestant minister that he was motivated by a desire to also “Christianize” the native people added another element of bigotry, anti-Catholicism, since the population was largely Catholic and thus already Christian.

Ida McKinley had an unconventional and far more mystical mission in mind.

Katie McKinley.

The trauma of having lost her two young daughters, three and a half-year old Katie in 1875, and four-month old “Little Ida” in 1873, led her to reject most tenets of her Presbyterian faith yet blend a belief in essential belief in the necessity of Christian baptism with the hope of reincarnation promised in Hinduism.

She insisted he retain the islands because she believed that her daughters might have been re-incarnated as Filipino babies.

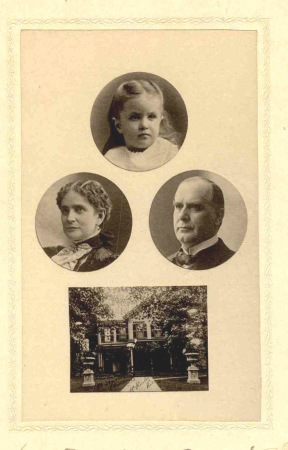

An 1896 campaign souvenir card showed not just William and Ida McKinley but their long-dead “ghost girl” Katie.

William and Ida McKinley spoke openly of their daughters, especially Katie who had matured enough to the point of developing her own personality. Newspapers about the romance of the couple always included reference to their daughters, along with great detail about them, provided by the First Lady.

During the 1896 campaign, Mrs. McKinley had even insisted that a souvenir card depicting her and the candidate printed and sold to those attending his speeches and rallies also include one of the only two known images of Katie.

By the time the McKinleys were in White House, the American public had become fascinated with the tale of their “lost girls,” or “ghost girls” as one reporter called them.

A tourist poses with the markers for Little Ida and Katie McKinley.

Back in their old hometown cemetery, the gravesite of Katie and Little Ida McKinley became a tourist stop. With the white marble Victorian angels topping their resting place, the rather ghoulish scene was even sold on postcards and stereo-optical cards.

A friend gave Ida McKinley a diorama Easter egg showing Katie and Little Ida on the White House South Lawn.

The First Lady never discouraged strangers from speaking or asking about her “ghost girls.” On the contrary, she loved speaking about her daughters – or what she imagined they would now be like.

Among the many trinkets and gifts she received from the public, for example, none was more valued and precious to her than the candy egg given to her at one of the annual White House Easter Egg roll events. Inside a small opening was a diorama of the South Lawn, showing Katie McKinley and Little Ida McKinley walking up to the mansion, to be united again with their parents.

And curiously, the trauma of having lost her daughters may have even factored into the McKinleys decision to host their Valentine’s Day dance.

The composition of this guest list may reveal even more about the Valentine’s Day event. The extra guests invited for the dancing were almost exclusively composed largely of young adults, all of them single and of dating age.

A Valentine’s Day card from 1900.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, it wasn’t just white elite families of Washington but all classes and races across the country who had begun celebrating what began as the feast day of St. Valentine’s as a wintertime holiday most often marked by dinner dances. Ever since the 1860s, both men and women in the United States had been sending red and pink heart cards to their sweethearts or those they hoped to date or even marry.

A mid-winter harlequin masked ball, usually held the night before Ash Wednesday.

The Victorian Age may have been receding but the high drama it placed on romance had left its mark. Coming as it did just before the solemn Lenten season, mid-February also marked the last chance to enjoy socializing for several weeks and dance balls on the eve of Ash Wednesday, often with guests required to disguise their identity in harlequin masks or full costume but were eclipsed by the appeal of Valentine’s Day.

For the highly-sentimental First Lady of the land, there could be no better time to encourage romance among young people.

Considered young to appear at the McKinley Valentine’s Day dance, Alice Roosevelt nevertheless attended.

In the years since the death of her infant and toddler daughters, Mrs. McKinley had been imagining them maturing as time went on so that when she encountered young women of different ages she would look deeply into their faces, as if searching for some imagined evidence or resemblance to her “ghost girls.”

The First Lady composed a guest list chosen from the sons and daughters of the capital city’s social and political elite.

Alice Roosevelt, the eldest daughter of the new Vice President, was even permitted to appear at the event, despite the fact that she had made her official “debut” to elite society but would do so at a ball that would be held in the White House for that purpose a year later.

Press coverage of the event was routine, in the social columns, reported as just another McKinley official dinners.

A poem published during the McKinley presidency longing for a return of dancing to the White House.

Still, in the history of the White House, dancing it was a relatively rare event.

Anecdotal history suggests that Dolley Madison hosted a dance. John and Julia Tyler held a large ball as their grand finale before leaving the White House – but it was considered immoral by many newspaper critics at the time. Mary Lincoln held a February ball in 1862 and was severely criticized for doing so in wartime; that night her son Willie succumbed to the fever that killed him. Another White House dance did not take place until 1889, hosted by Mary McKee, the adult daughter of President Benjamin Harrison

Despite the rarity of such a social event and even the risk of irritating moralists who opposed dancing, the presence at the White House of her favorite cousin Mary McWilliams’s daughter that seemed to have prompted Ida McKinley to conceive of such a party at all.

The fact that the “delightful innovation” of dancing that took place on Valentine’s Day might appear to be a seeming after-thought. There were no mentions of any special red or pink desserts, heart-shaped souvenir favors or other elements that marked it as a holiday event. But there was one good indication it was quite intentional.

Ida McKinley chose a variety of pink and red primrose, carnations, orchids, roses, trumpets and azaleas to be displayed on the White House state floor for her 1901 Valentine’s Day dance, including President McKinley’s trademark red carnation, upper right.

While many a First Lady was known to love flowers, Ida McKinley was especially enthralled with them. She used those grown in the White House conservatory to send bouquets as a sign of her political support to organizations, like Susan B. Anthony’s suffrage convention, or to those she learned were ill or suffering.

While she took no interest and offered no opinion on food served to guests, she was directly involved in determining all the floral arrangements for social events.

And, for the February 14, 1901 dinner and dance, Mrs. McKinley chose to have the rooms and tables adorned with red and pink roses, crimson trumpets, pink primrose, pink carnations, pink orchids, red azaleas and, in a nod to the President, the red carnation – which he famously wore in his buttonhole and which, after his assassination, was made the state flower of Ohio in his honor. The floral hues that night seem to have signaled the romantic First Lady’s intention.

The invitation to so many young adult women guests at the dance was not merely an indication of the potential romance of the night, however. Mrs. McKinley had relied on her and the President’s unmarried nieces to appear at her side in past social seasons as a sort of assistant hostess, taking the place she would have given to Katie – but she never assumed the prerogatives of parenthood over them. Nor did the First Lady think that any of her young women guests might somehow be her reincarnated daughters. It was more her wistful rumination that, had they lived, Katie and Little Ida, would now be leading lives like her guests, dressing, dating and – dancing.

A toddler girl angel intended to represent Katie McKinley was sent as a Valentine’s Day greeting to Ida McKinley.

These young adult women guests who had reached the age where they could attend social events on their own and fall in love with the young men also invited to her Valentine’s Day dance could have been Katie and Little Ida.

In fact, after one White House reception when the presidential couple were both taken with a young adult woman guest, they both retired to their bedroom, musing and imagining how wonderful it would be for them had the young adult woman really been Katie herself.

Hearing the story of her “ghost girls” one of the guests at the Valentine’s Day dance later sent the First Lady a color graphic image of a golden-haired little girl, intended to represent Katie McKinley on a valentine heart.

It is likely the earliest known such greeting card sent to First Lady, but that sort of benchmark had no importance to Ida McKinley.

What mattered was that, beyond her and the President, Katie McKinley was being kept alive in the collective memory of others as well, a somewhat haunting legacy of the first White House Valentine’s Day dance when ragtime first echoed through the old mansion.

Categories: African American History, First Families, The McKinleys, Valentine's Day

Tags: coon songs, Ida McKinley, John Philip Sousa, racism, ragtime, Valentine's Day, White House, William McKinely

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  The President as King: A Political Cartoon History

The President as King: A Political Cartoon History  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Leave a Reply