Liz Taylor & Jackie Kennedy.

Take a time machine to the Jet Age, that sweet thin spot in the 60s and two brunettes stare you down from every corner newsstand or grocery checkout line.

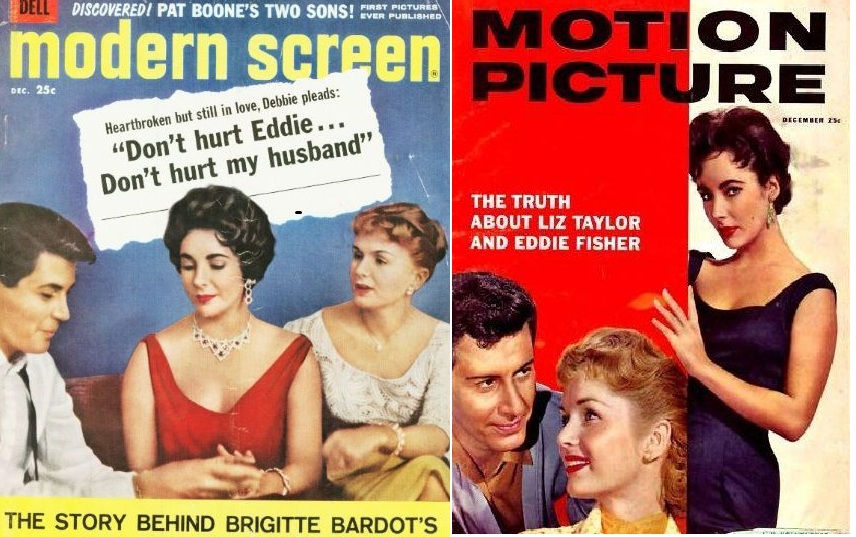

For every Khrushchev, or John Glenn, Ringo, George, Paul the new Pope or Princess Grace on a magazine, there were five of “Liz” and “Jackie” on a tabloid. If it wasn’t a cover story comparing and depicting Actress Elizabeth Taylor and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, it was an artful blending of a headline about one with the image of the other, subliminally planting their relationship in the public imagination.

Which is the only place where it ever existed.

With Taylor’s death last week the revelation that she was a great-grandmother will disconnect from collective memory, but only briefly. In the decades after her nadir of fame and that of Jackie Kennedy the mortal lives of both continued to occasion squibs and snapshots for the public, from Liz going bald after chemo to Jackie walking grandkids.

But the impression of even Liz waiting patiently in a wheelchair or Jackie getting hot from jogging prove ephemeral after prompting back the indelible half-century vision of tawdry and tragic times shared by the tempestuous Actress and cool First Lady.

Rumor dies hard. Persona never does.

Knowing this, tabloids boldly grasped at stars, giving them secret lives that made them familiar to anyone waiting for a root canal or under a beauty parlor dryer, if not to themselves.

By the end of the 50s, the last throes of the Hollywood studio system meant the end of contract actors and protection of their reputations as property. As arranged by in-house publicists, upbeat fan magazines like Photoplay, dominated the genre, posing well-lit swells as paragons of purity. There was also the other end of the spectrum.

Those actors who faced legal charges of adultery or drunk driving might find unflattering candid snapshots of themselves emerging from the police station in Confidential, unless a studio head suggested ditching the dirt would prove penny-wiser than dishing it. While the few publishers of movie star magazines would find a more open market by no longer being constricted to withhold the truth, they had to tread artfully, mindful to spin provocative facts that kept stories just legally short of libel.

The ad revenue potential from the lucrative market demographic of housewives, however, remained irresistible. Juicy stories always concluded on the back pages beside cosmetic, diet aid, wig and sexual enhancement ads, placed there to capture the aspirations of women emulating the “stars” they envied or worshipped in the front pages.

What emerged was a new hybrid tabloid with stories on stars who symbolized both virtue and vice drawn neither too naughty nor nice. To hook readers into buying the magazine serially a running conflict was best. Before the summer of ’58 was over, a scandal rocked Tinseltown that drove itself to the bank.

Until that point, 26 year old strawberry-blonde actress Debbie Reynolds, a “girl next door” type was sweetly wed to crooner Eddie Fisher who publicly referred to her as “my princess.” It kept the romance crowd purring but proved tough on reality. A tad lonesome with her Eddie on tour, Debbie phoned to perk up a true-blue pal alone in her hotel room, just then down-in-the-dumps, recently-widowed Liz Taylor. Debbie had been bridesmaid for Liz when she wed third husband Mike Todd, Eddie’s best friend and best man. Liz didn’t answer the phone. Eddie did.

By October, the earliest possible printing once the story hit, love triangle tales dominated the supermarket aisles.

Quickly detecting that catfights sold better, the tabs got fatter months with leading headlines and superimposed images of double-crossed Debbie versus home-wrecking Liz. On May 12, just when they felt dry, the tabs tapped a gusher: three hours after Eddie divorced Debbie in Reno, he wed Liz in Vegas.

If a solid year of the story sold tabs, it also soiled Liz, morphing her persona from professional working mom into low-cut siren. In April of 1960, making her first big public appearance with Eddie at the Academy Awards, she failed for the third consecutive year of being nominated to win Best Actress.

Industry tipsers were soon abuzz over how badly Eddie was beating her image. Debbie predicted Liz would soon dump him but in announcing her own Mr. Next, the former Mrs. Fisher bailed from the game. Their gravy train nearing its last station, the tabs could hardly realize there was another station just over the horizon ahead, in Washington.

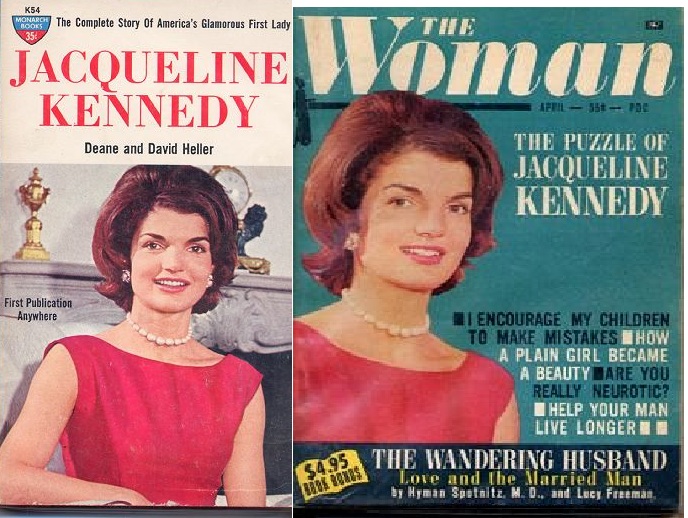

The greater battle that fall was the presidential election between Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy and Republican Vice President Richard Nixon; within it, a smaller one of seemingly inconsequential currency was burgeoning into an issue fraught with political symbolism that could potentially influence perceptions to tip the tight race.

Detecting a Parisian influence on clothes worn by Kennedy’s mother and wife, Women’s Wear Daily printed its investigative conclusion that they spent some $30,000 on their annual wardrobes. When a political reporter cornered Jackie on it, she quipped, “I couldn’t spend that much money on clothes “unless I wore sable underwear.”

Annoyed, the ex-reporter moved on to talk about nuclear arms, but not before firing her own missile by adding the fact that Pat Nixon bought pricey numbers at the little dress shop in Elizabeth Arden’s salon. The War of the Wives was officially declared by the Washington press using the Hollywood tabloid Liz-Debbie strategy. Sideshowing the Kennedy-Nixon debates were now cartoons, talk-show jokes, a newspaper interview that put former Democratic President Truman in the position of defending Nixon’s wife, and a Newsweek cover looking more like Photoplay than Time.

Before Debbie could say “I do” to her second husband on November 25, Jackie’s first husband was elected president.

Monarch Books rushed out a quickie paperback to hit the drugstore racks by the January 1961 Inauguration, regurgitating facts already known. Using the same picture of her, “The Woman,” a monthly self-improvement pulp magazine put her on their April issue with more questions than answers in the article, “The Puzzle of Jacqueline Kennedy.”

With lead times up to three months, the tabs stood by helplessly as daily papers and news weeklies scooped them. Jackie’s quick-jelling persona of graceful motherhood, marital bliss, and tasteful trendsetter had a better chance of flattening sales from reader boredom than boosting them.

Jackie was too good for the tabs. She needed a foil.

Three months after the Inaugural, shimmering on the opposite coast Liz finally won the Best Actress Academy Award (for Butterfield 8) on April 16. If Miss Taylor’s star power was affirmed and respect for her work restored by her Oscar, her Eddie had cast her as bad girl. Not even being a good mother mitigated that.

The klieg lights turned back brighter on Jackie in May. Joining the President in their first overseas trip, she caught the globe’s attention as she glamorously glided through Paris, Vienna and London in glamorous gowns and chic suits, wittily charming world leaders.

When the President went home, however, she stayed with her sister, a “Princess” by marriage to a deposed Polish noble to party with her Jet Set crowd in Greece. Indulging in the high life and letting the nanny continue to watch her toddler and infant at home was just enough to shade Jackie’s glow.

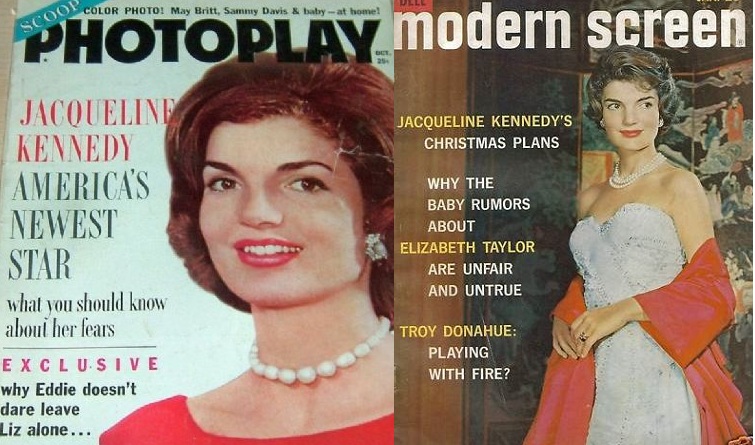

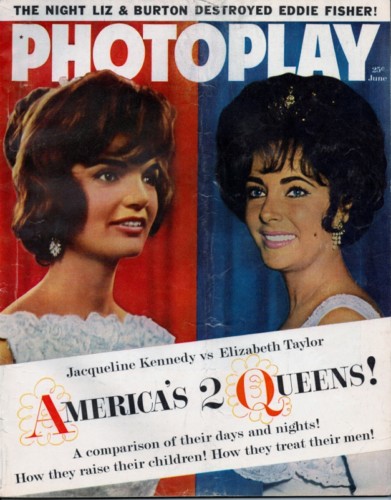

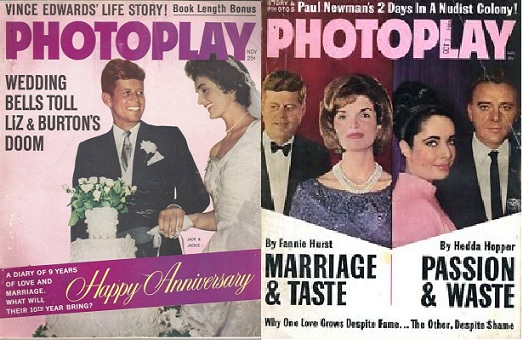

In an era when Presidential families were still treated reverentially, the tabs had to tread lightly in covering the First Lady to avoid an indignant backlash. Oldest and gentlest, Photoplay broke the ice in late August, releasing their October issue, with the lead story of “Jacqueline Kennedy: America’s Newest Star,” a happy proclamation of why her fame put her in league with young and pretty movie stars, but with a brush of dark prurience, offering “what you should know about her fears.”

Photoplay was thus justifying its open season exploitation of the wife of the President of the United States as something of a public service to keep citizens informed.

Even more intriguing was the “exclusive” headline below it in red lettering: “Why Eddie doesn’t dare leave Liz alone…”

Liz, it would seem, had demons, not unlike Jackie’s fears. Liz got a new Debbie, of sorts; Jackie, her foil.

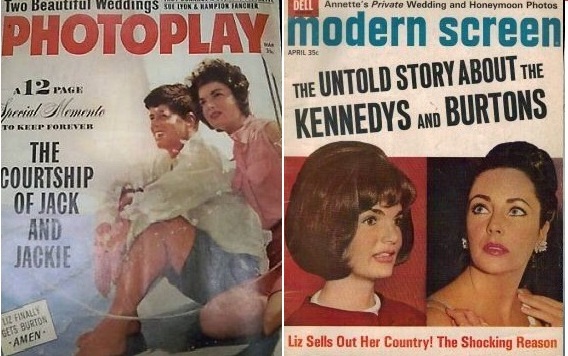

Tentatively, the formula worked. Imitation being the highest form of flattery, Modern Screen put out its January 1962 issue early, Jackie baring shoulders on the cover to advertise a tame tale on her “Christmas plans.”

Perhaps the holiday spirit hit the tab which offered a sympathetic headline beside Jackie’s picture: “Why the Baby Rumors about Elizabeth Taylor Are Unfair and Untrue.”

If the “mom angle” on both women smacked of pablum, at least it would let the ladies at home raising new children of the Baby Boomer subset, “Generation Jones” (born between 1958 and 1964) relate to them. The year 1962 saw a rise in cover stories selling maternal Liz, albeit while simultaneously suggesting that some believed her to be an unfit mother and that her kids might be taken away from her. Even a valentine piece on Jackie’s daughter used the First Lady’s image (but not her name) to promote a cover headline banner of Liz-as-Mom, announcing adoption plans they made up for her.

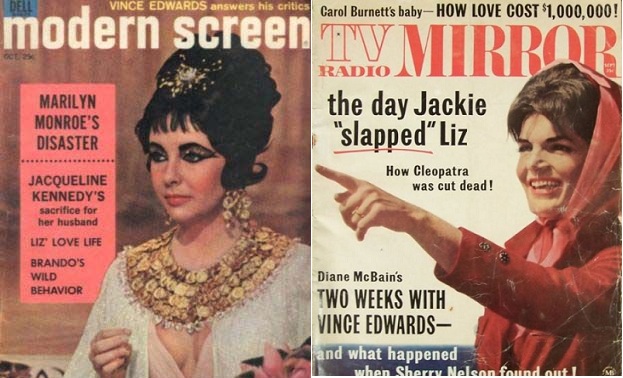

Besides motherhood and their dislike of being addressed by their popular nicknames, Liz and Jackie were also both depicted as being gaga for diamonds, the latter having worn an eye-popping sunburst pin of the jewels in her uniquely shaped hairdo a year earlier in Paris. In February, Modern Screen used it to try the first reverse the new tab duo, with Liz on the cover in the same coiffure and similar diamond, alongside the headline, “Hints from Jacqueline Kennedy’s Paris Hair Stylist,” proving that the tawdry Movie Star was now copying the classy First Lady.

Not so fast Liz!

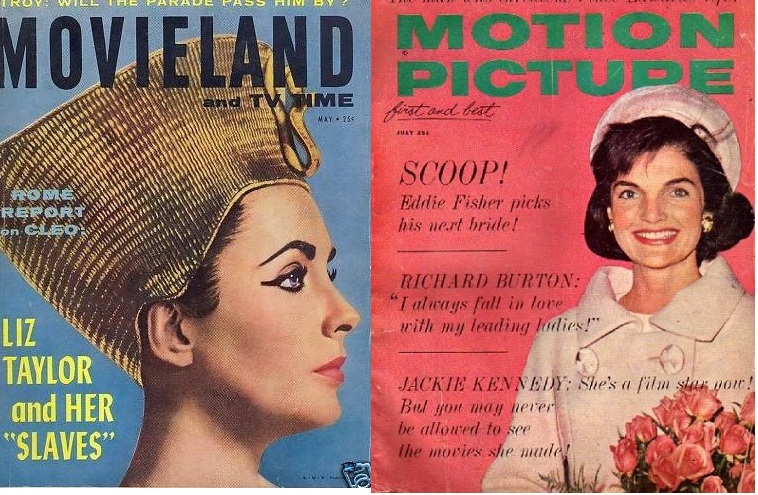

So Motion Picture would soon point out on Jackie’s behalf.

\The First Lady was copying the Movie Star – by becoming one herself! Balancing emphatic fact with vague suggestion, Jackie was indeed slated to be a “film star,” even though readers “may never be allowed to see her movies.”

Her visit to India and Pakistan that March had been filmed by a crew from the US Information Agency and edited into a full-length feature documentary intended for free distribution in commercial theaters – until Republicans killed the idea as Administration propaganda.

Although that July issue of Motion Picture put Jackie on the cover without mentioning Liz, the implication of a potential rivalry between the women was suggested by the other male name beside Eddie Fisher who got a headline, and this guy’s quote that, “I always fall in love with my leading ladies,” seemed targeted at Jackie, smiling in shades of girlish pink. The actor in question? Richard Burton.

The duo interchangeable, tab heaven was reached. Once-modest Photoplay was ready to now formally coronate the two women who were making them the most money, creating the first cover with both Liz and Jackie together in June 1962.

The First Lady being paired with scandalous Liz hit a nerve with many Americans, some of whom wrote the White House, outraged in the belief it had cooperated. In the Kennedy Library archives, a paper trail involving presidential advisor Ted Sorenson had him contacting the Better Business Bureau, urging them to dictate some control over the fan magazines.

The images and depictions of Presidents and First Ladies, however, are public domain; at best they could be shamed for breaching taste – hardly a concern of the tabloids.

While Jackie had been visiting India, Liz was in Italy, filming the motion picture spectacle of the era Cleopatra, starring as the legendary Egyptian Queen and becoming the first actor to earn a cool one million for a movie.

Not long into shooting, she fell in love with her married co-star and rogue Welshman, Richard Burton and a passionate affair began. Eddie was over.

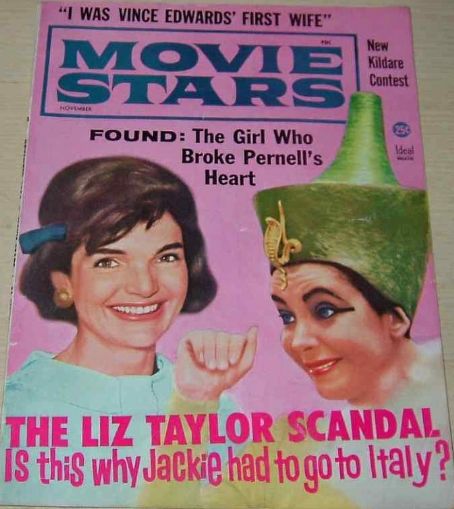

While the news that Jackie was heading there too, that summer did not eclipse the new Liz-Dick saga, pictures showing the First Lady motorboating the Amalfi Coast, hanging out at cafes, going to nightclubs with men other than her husband, like Fiat tycoon Gianni Agnelli, the tabloid Movie Stars emitted the first whiff of scandal, suggesting Jackie had looked at the fun Liz had and said, “Give me what she’s having!”

If Liz was temperamental and Jackie was cool, neither could be predictable. With a touch of assured saintliness, that show-biz gal so loved her kids, they came before even Burton! And that Sunday afternoon in sunny old Italy?

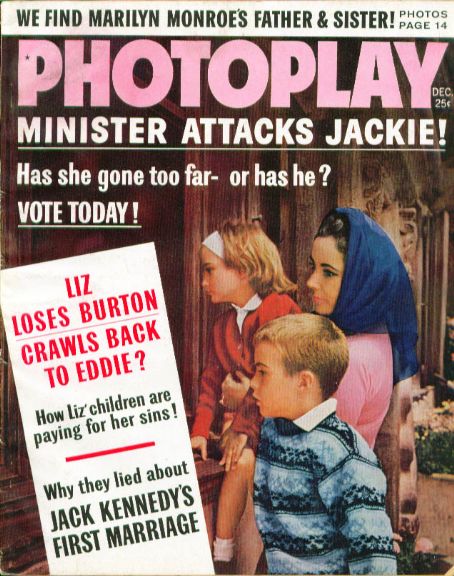

The society-dame ditched her veil after church to slip on a skimpy swimsuit and then went- swimming, sure making her a sinner! At least according to an obscure Baptist preacher, “Reverend Ray,” who soon attacked Jackie for being seen that way on his weekly radio show.

Now Photoplay went all out, using this to banner its December 1962 issue, daring to ask if it was Jackie who “went too far,” and offering readers a chance to vote on the matter…if they bought the magazine and cut out the ballot inside to send in.

With a picture of Liz with her children and wearing a headscarf against the backdrop of a church interior, she looked like a reformed sinner pondering the deeds of a reformed saint.

Not every tab followed this emerging narrative. While the interchange of face and headline between the two prevailed, some like Modern Screen and TV Mirror continued to depict Liz as sexually promiscuous while Jackie – as one headline next to Liz’s picture put it, made a “sacrifice for her husband” (turns out it was public life, not intimate matter).

With the release of Cleopatra, Jackie was cast as moral arbiter and claimed to have “slapped” her bad girl counterpart, a euphemism for the story’s revelation that she was a no-show at the movie’s premier. Actually, not only do the Kennedy archives show that Jackie wasn’t invited, but when a crusading group called “Concern” wrote the First Lady asking that she join in protest against the “barnyard morals” of Cleopatra, Jackie refused.

Under the signature of adviser Arthur Schlesinger, she spoke out against censorship, citing examples of fine literature such as Huck Finn and Catcher in the Rye that would have been lost had calls to ban those works taken hold.

As long as Liz was loving Dick both were living in sin, each married to other people. It was the great leading difference between the two tab stars, and a point Photoplay emphasized in November 1962 and November 1963 to mark the wedding anniversary of the Kennedys.

And yet again, employing the most overt demonstration of subliminal advertising, the first of these used an image of Jackie as a bride with a cover headline about Liz as a bride.

The latter one was still on some magazine racks when the news from Dallas came on November 22 of the President’s assassination. Luckily for the tab what proved to be the last time Jackie appeared on their cover as the First Lady its description of her praised her “taste” in contrast to Liz’s “waste.”

In a matter of weeks, Liz would join Jackie’s side of the marital fence, her divorce from Eddie made legal on March 6, 1964. There proved little time, however, to tinker with the new narrative, however, and begin pitting both women against each other for the same man.

On March 14, Liz the siren finally married Dick the rogue. In the shadow of the President’s death, however, and a sentimental commemorative of the Kennedy courtship, Photoplay dismissed it with a small banner “Liz finally gets Burton. Amen.”

Just one month later, however, the tide would begin to turn, starting with closer comparisons between Jack and Dick and Jackie and Liz.

And as the young widow soon entered the hipper 60s as a swinging single while the raucous newlyweds were swinging champagne bottles at one another, the tabs took Liz and Jackie down roads of shock and scandal unimagined in the Jet Age.

Categories: First Families, Hollywood, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Myths, The Kennedys

Tags: 1960s, Bobby Kennedy, Cleopatra, Jackie Kennedy, John F Kennedy, Liz Taylor, Richard Burton, tabloids

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  The President as King: A Political Cartoon History

The President as King: A Political Cartoon History  The First White House Valentine’s Day Dance: the McKinleys, Ragtime, Racism & The Romance of the “Ghost Girls”

The First White House Valentine’s Day Dance: the McKinleys, Ragtime, Racism & The Romance of the “Ghost Girls”  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Leave a Reply