Seven days after her husband’s presidency began, First Lady Barbara Bush was in the Oval Office reviewing and signing documents on the President’s desk.

At a press round table in March of 1989, the new First Lady Barbara Bush declared to the press corps who covered her activities:

“Yes, I’m a liberal. I don’t mean that as knocking the Republican Party, because I think of the Republican Party as liberal on social issues….You may not look at me that way….[but] you have to look at the big picture like what will help people most….I don’t mean that conservatives don’t care.

Labels are for cans.“

Her self-description was accurate. Born in an era when that was the party which led the fight for a woman’s right to vote, and sponsored the Equal Rights Amendment for women, maturing at a time when the “party of Lincoln” combatted the institutionalized racism of the Democratic “solid South” and, at a time when she was a young wife and mother, it was the party that initiated civil rights legislation.

Barbara Bush was indeed among the last of the nation’s outspoken Liberal Republicans.

Barbara Bush leading Hillary Clinton by the hand into the White House during the 1992-1993 transition.

Most recollections of the former First Lady following her death last week, pointedly categorized her as unpolitical since she hadn’t overtly involved herself in policy as would her successor Hillary Clinton. She didn’t craft executive legislation nor lobby congress for passage of any.

Instead, Barbara Bush focused on the human beings who could be affected by policy, as well as charitable support.

And she also did lobby on pending legislation, in private. Publicly, she focused on symbolic gestures, knowing this covert route could still have a political impact, if just not as immediately as policy.

It’s true; symbolic gestures don’t have the impact of sweeping federal legislation. And by having a presidential spouse give voice to views at odds with the changing nature of her husband’s political party, a fair question arose: Was it merely a way of suggesting to those who opposed Republican policies from 1989-1993 that it had a supportive voice within the presidential family, dangling the promise that she would do all she could to influence legislation – yet without the intention of ever doing so?

For a person who embodied a practical reality, there was no such machiavellian intention.

Barbara Bush’s agenda, however, was far more complex than changing legislation.

Her agenda was, in some ways, more difficult. It was about changing attitudes and opinions on the most basic humanitarian principals, about making individual citizens use their minds to look into their hearts.

In 1991, Barbara Bush listens to one side of her husband’s conversation with Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev as the Soviet Union’s communist government was collapsing. Although she was known to be kept in the loop, even on top secrets, she offered her political opinions strictly in private to him.

In the long run, she believed, that shifting attitudes would create as much if not more of a more indelible change in the lives of everyday citizens than federal legislation could.

And in that belief, she adhered to two core “liberal Republican” principals: justice and dependance on the private sector.

If Mrs. Bush was known by her tart tongue, she also disseminated a plain and sensible compassion when it came to focusing attention on those hit hardest by the nation’s larger social problems.

To change thinking, she believed, the first step was to change comprehension.

In reviewing national statistics at the time, she saw a connection. She thus used the issue of adult illiteracy (a distinction from teaching children to read) as a way of addressing social problems that saw a sharp increase in the 1980s, from homelessness to unplanned teenage pregnancies. About 35 million American adults couldn’t read above the eighth-grade level, and some 23 million were “functionally illiterate” unable to read or write beyond the fourth-grade level.

Her political loyalty was more Bush than partisan.

While she knew the task of eradicating ignorance on matters involving self-responsibility was both nebulous and overwhelming, she also knew that both formal education and self-education were necessary to at least begin addressing it. “There are many types of slavery and education is the key to freedom. I can’t tell you all the people I’ve known who have escaped the bondage of ignorance,” she stated in her 1989 commencement speech to Bennett College, a small African-American women’s school in North Carolina.

Barbara Bush effectively used both her appearance with white hair and wrinkles and her family status as a mother and grandmother to adopt the persona of, as she put it simply, “everybody’s mother.”

Mrs. Bush did not hesitate to use hot-button expressions like “racism,” “affordable housing,” “catastrophic health insurance,” and “gun control” not by issuing dramatic public statements, but in the natural, even casual course of her conversation with the press. At the same time, she avoided social issues that would quickly lead the conversation into her being asked to even simply re-affirm her earlier known support of the Equal Rights Amendment and Roe v. Wade. It wasn’t that she had lost her opinion; it was that she didn’t want her opinion to garner headlines that would eclipse or complicate the President’s opinion.

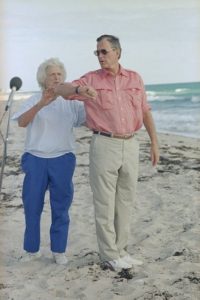

The Bushes during a beach front news conference in 1988, Florida. She knew her own tendency to blurt out her opinions and once her husband was elected president, she tried to watch what she said.

If often acerbic in expressing the opinions that she did, they genuinely stemmed from her maternal instincts of warmth and strength.

Still, despite the limits she placed on her political opinions, she often didn’t think through how to best express what she did intend to say – before just speaking out. Repeatedly, her words came out garbled or insensitive, or confounding. Sometimes, she did slip, blurting out her views in a way that seemed at odds with Administration policy and, as Washington Post reporter Donnie Radcliffe put it, “she’d realize it about halfway through and then began to backpedal, contradicting herself.”

Her unfiltered assessment of the facts as she saw it, however, could be seemingly contradictory, and read as blind insensitivity or spoken for the sake of shock value. The best example of this were her flippant remarks as a former First Lady about Hurricane Katrina victims being largely poor and suggesting that accommodations in the Houston Astrodome might be better than what they were accustomed to. She made such a mess and experienced the first real mass criticism for it that she didn’t even attempt to later explain what she might have meant to say.

I have my own personal experience with this. When I introduced them at a large 1994 gathering, my mother piped up, “Oh we have some things in common,” to which Mrs. Bush said, “You mean we could both lose a little weight?” My mother held her own. “No, we both have four sons and one daughter. And suffer from Grave’s Disease.”

To her credit, Mrs. Bush later secured my address and wrote an apology, explaining herself. One thing true about Barbara Bush that is uncommon among political figures, she was always the first to admit her mistakes and apologize for anything hurtful she said.

And, if you were on solid factual ground, once you snapped back at her to say she was wrong, she not only enjoyed the repartee but would concede if you were correct. I did so on three occasions.

George and Barbara Bush visiting with children who had to find shelter in the Houston Astrodome during Hurricane Katrina.

There was further context for her remarks about Hurricane Katrina victims. She had been walking through the thousands of people, followed by a reporter who carried a tape recorder and made a number of abbreviated observations in response to questions he managed to get to within her earshot, none of the dribbled phrases seeming to be connected. Also never mentioned is the fact that it was not her expected responsibility to even visit those sheltered there or answer press questions. She was no longer a president’s wife but technically a private citizen. If her being mother of the president somehow obligated her presence and observations, it was certainly a first. None had expected presidential mothers Lilllian Carter to meet with Indochinese refugees in 1979, or Rose Kennedy meet with freed Cubans in the Bay of Pigs aftermath in 1961. Why had Mrs. Bush come in the first place? Because she actually did care.

In the White House just before the Internet forever altered the world, Barbara Bush also effectively used the media to convey her views, posing for thousands of “photo ops” at a time when national newspapers were finally able to print the photographs it published in color. Thus, Barbara Bush’s symbolic gestures were important not just as a bellwether of an era but in their value as a tool to at least get people’s attention and perhaps awake awareness of suffering, if not entirely change their thinking.

Technology may have killed 21st century society’s familiarity with nuance, but to accurately assess the impact of Barbara Bush on the nation over which she was granted a position to offer commentary upon, nuance is necessary. There was, in fact, nothing but nuance when it came to determining her partisanship.

While she was dogged in helping her husband pursue the presidential nomination three times (1980, 1988, 1992) and election twice (1988, 1992), it naturally committed her to a Republican Party. Yet it was a party that was just then accelerating from a fluidly progressive philosophy on social issues to an rigidly exclusionary one of “litmus tests.” Barbara Bush remained unapologetically a proud Liberal Republican.

While she campaigned for her son’s pursuit of the presidency, she also disagreed with him on several social issues and grew increasingly public about that fact, he respecting each of their own right “to agree to disagree.”

There is no greater way of grasping this nuance than to look at how she viewed the presidency of her son, George W. Bush. She loved and supported him as thoroughly as she had her husband – but she also didn’t care if it publicly leaked that she did not agree with his policies on issues from stem cell research to limiting a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

In truth, Barbara Bush would always identify as Republican because she was committed to the leadership of her husband. What that really meant to her, however, was just continuing her earlier commitment to social justice, to fairness.

There’s no greater proof that she was more loyal to principals she once considered analogous to republicanism than she was to blind partisanship than the fact that she made it clear she wasn’t voting for the 2016 Republican presidential candidate. Her other son Jeb had already been beat and, as tradition always had it, a person with her partisan history would usually then offer at least a word of support to the final nominee in the general election. Further, Barbara Bush refused to deny that she had voted for the woman she “ran against” in 1992, Hillary Clinton, the 2016 Democratic presidential candidate.

It is too easy to write Barbara Bush off as simply an adherent to the old principal of noblesse oblige “to whom much is given, much is expected” for there’s always been a hell of a lot of very rich people who didn’t give a damn about anyone in need. She didn’t have to. But she did.

Here are some encapsulated examples of those words and deeds spoken and carried out by Barbara Bush as First Lady.

African-Americans:

With Rosa Parks in the Lincoln Bedroom, looking at a portrait of the late president; she also showed the civil rights leader an original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation, February 1990.

Barbara Bush witnessed racism first-hand. In 1957, when she made her first long drive with three of her young sons from their home in Texas to her husband’s family summer estate in Maine, Barbara Bush was joined by a young woman her husband had hired to help her make the trip. She happened to be black. George Bush had specifically planned their stops at places “to avoid racial incidents.” They weren’t so lucky on the way back. The African-American woman was denied entry into restaurants and motels.

“That was unacceptable to me,” she later admitted. Instead, she bought food for all of them at rest stops and they all picnicked and slept in the car until finally spending a night in a Howard Johnson’s that would accommodate both black and white. The women had “long, interesting conversations” about racism, and Mrs. Bush admitted, “my eyes were opened to an aspect of life that was inconceivable to me. I was so ashamed of our system that could tell this fine woman she was not equal….I’m not sure if I really appreciated how protected my life had been – and always had been – from such ugliness.”

Barbara Bush did not get involved or influence any legislation but she again used the powerful symbolic role of First Lady to send a message of her support to the African-American community, once again – largely through education. Besides this, however, she focused on African-American history, a subject she became particularly knowledgable about, as a way of pointing out those from earlier times who had faced not just societal but institutionalized bigotry and yet rose to achieve.

Mrs. Bush and Mrs. King at the 1998 Republican National Convention.

During the 1988 convention that nominated her husband, Mrs. Bush knew that live cameras were also focused on her during the proceedings. Learning that the widow of slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was at the event, she asked that Coretta Scott King be invited to come sit with her. If it obviously helped the Bushes appear more empathetic to African-Americans, it also was an act no previous presidential candidate or their spouse, or incumbent ones seeking another term had done. In fact, after the election was won and there was no cynical need to win by employing helpful optics, Mrs. Bush made certain that Coretta King was also invited to all the Inaugural events. They remained friendly during the Bush presidency as well.

Upon her husband’s election, Ebony magazine declared that Mrs. Bush was “politically and personally committed to equal rights for Black Americans,” and predicted that “she will not hesitate to use her highly visible role to prove it. ” It was already whispered that, however unsuccessfully, she had voiced her anger against the racist Willie Horton television advertisement her husband’s campaign manager Lee Atwater had pushed through to help Bush among white voters.

Her sense of justice did manifest immediately as she specifically sought to hire an African-American for “the most visible person on my staff,” making Anna Perez the first black woman to serve as Press Secretary to a First Lady.

Anna Perez and Barbara Bush watching TV together in the White House family quarters.

Mrs. Bush’s efforts on raising awareness of African-American history and issues, as well as racism were largely confined to public statements and appearances she made.

She became the first First Lady to publicly celebrate Martin Luther King Day, heading to a local school and joining a line of participants in linking hands and singing “We Shall Overcome,” and then taking part in an early Black History Month celebration. She brought national attention to a photography exhibit, “I Dream A World: Portraits of Black Women,” by visiting the museum where it was on display and meeting there with African-American curators and photographers. She had no hesitation in naming Texas liberal Democratic congresswoman Barbara Jordan as one of four African-American women she considered a national leader and went on at length about the importance of abolitionist Frederick Douglass by detailing his accomplishments in an interview.

She never had any false sense of her influence as a “white-haired white lady,” among African-Americans but she would address racial issues as they arose, calling on those black men and women who’d forged successful careers for themselves but “don’t go back to help” to serve as the best role models. She was “not naive enough” to believe other white people were as interested in African-Americans and admitted to noticing how other whites stared at her press secretary as “the only black person in the room.”

She never avoided discussing the reality of incidents and problems that beset some of the African-American community.

After a black male was falsely accused of murdering a pregnant woman and killing her husband in Boston, the First Lady stated that, “it made me sick. And it isn’t just in Boston. We have racial in our country and we’ve got to do away with it. I will continue to speak out like I am right now.” And when Black Muslims began to patrol an inner-city neighborhood development plagued by drug violence, she supported the effort of the controversial group and pointed to their apparent success, quipping, “Right on.”

George and Barbara Bush with their friend Louis Sullivan, named Secretary of Health and Human Services with the influence of the First Lady.

Barbara Bush had been a supporter of the United Negro College Fund and was a close friend with its president William J. Trent, Jr. for some forty years. From 1983 to 1989, she was a committed trustee of Atlanta’s Morehouse School of Medicine, the only four-year predominantly African American medical school founded in the United States in the 20th century. She wrote the foreword to The Morehouse Mystique, the history of the medical school,

She is credited with having successfully lobbied for her husband making Louis Sullivan as his Health and Human Services Secretary, the only African-American in the Bush Cabinet.

Sullivan said, upon learning of her death, “Barbara Bush was committed to the concept of equal opportunity for all Americans.

Gay Rights:

At the wedding of friends, 2013.

“I appreciate your encouraging me to help change attitudes…I firmly believe we cannot tolerate discrimination against any individuals or groups in our country. Such treatment always brings with it pain and perpetuates intolerance.” So wrote First Lady Barbara Bush to the president of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays – with the added granting of permission for her letter to be reprinted by any publication that wished to.

Barbara Bush’s support for acceptance of gay and lesbians in American life began literally on her first day as First Lady. Included among the members of both her own and the presidents extended families, she invited her gay niece and her woman partner.

Some point to Barbara Bush as being the successful inside advocate of the President signing the Hate Crimes Statistics Act, which covered homophobic acts of violence and intimidation. And at the public bill-signing ceremony of the HCSA, she invited the first openly-gay and open-lesbian individuals to such an event.

As a former First Lady, she expressed love and support for her husband’s chief of staff when he disclosed that he was gay. In 2013, with her husband signing as witness, Barbara Bush attended the wedding of their two women friends Bonnie Clement and Helen Thorgalsen in Maine.

It has been mistakenly suggested by some that all she did was attend a “family wedding.” The couple, however, were not related to either of the Bushes and they also had no problem in photographs of themselves posing with the women being disseminated in the media.

In what may be the most important statement she made, in her 1990 Wellesley College commencement speech, Barbara Bush addressed what she viewed as an elemental necessity. It was a remark that some believe was “coding” for her support of LGBT Americans:

“Diversity, like anything worth having, requires effort. Effort to learn about and respect the difference, to be compassionate with one another, to cherish our own identity, and to accept unconditionally the same in others.”

During her husband’s 1992 renomination at the Republican National Convention, Barbara Bush had a visceral reaction to right-wing radical commentator Pat Buchanan’s speech, laced with homophobia.

She said simply: “I hate gay bashing.”

Gender Equality & Women’s Issues:

Barbara Bush directs her husband in a task as they help clean up a land site for reclamation, four years after they left the White House. She made clear that beside being a wife and mother, she had worked her whole life, as an unsalaried volunteer.

There were a host of gender equality and women’s issues that Barbara Bush addressed as First Lady. While she herself made clear that apart from her work as a mother and wife, she had worked her whole life as an unsalaried volunteer, it was through her daughters-in-law and women staff that she became increasingly enlightened to the struggle for balance that women who pursued a professional career while also having a family faced.

While she viewed the role of parent as the most serious one people of their gender could assume, she never suggested women should sacrifice their talents and careers for it, or that it was an either or situation. But the conflict was a problem of middle-class women that was going unaddressed. “I don’t question it, I just say it’s harder. You’ve got to bite the bullet and pretend you’re not [tired] until you go to bed.”

Engaging with women of all ages, following her Wellesley College commencement speech.

Despite having married while still a teenager and then started a family, Barbara Bush did not necessarily advise this. “Im saying to young women, wait, you’ve got years to have a family.” In an era when the “yuppie” archetype arose, she also recognized that even without families, women who’d earned higher education and pursued higher the professional careers faced more challenges than did men.

“In a way, it seems so wonderfully liberated to have a whole world of opportunities so open to you,” she remarked in her famous Wellesley College address. “But it must present immense challenges. You have so many options that it must make it difficult to make choices and set priorities and establish limits. Because today it seems that women are often expected – especially by themselves – to be all things to all people and to be perfect in every role.”

With the president of Wellseley College, Soviet First Lady Raisa Gorbachev.

Again, Barbara Bush was not suggesting any legislation be initiated, she was merely acknowledging the reality of a situation that no political figures had ever addressed. There was nothing partisan about it. In fact, it was none other than the vice president of the liberal organization, the National Organization of Women who supported the First Lady, explaining, “Barbara Bush’s traditional approach is not harmful. It is a reality that many women are burning out now in the workplace….Her idea is that it is a physically impossible task to do it all, is the reality.” The president of the Women’s National Political Caucus concurred, supporting Mrs. Bush’s message that “you have the power to decide who you are and want to be.”

The First Lady made clear her belief that women were as qualified as men to hold any political office. She frequently pointed out the growing number of elected women at the local and state level, especially proud that Texas, “the most macho state” had three women mayors during her tenure as First Lady, but also believed her gender was as capable as males were as heads of state: “I think many women, certainly of my generation, can run the world.”

Secretary Martin watches President Bush sign legislation in the Oval Office.

Making good on her remarks, she went to campaign in Illinois for U.S. Congresswoman Lynn Martin, then seeking the U.S. Senate seat, a fact that raised many eyebrows given that the congresswoman had been one of several Republicans who privately lobbied and publicly called for President Bush to declare himself pro-choice on abortion. When Martin lost, Barbara Bush encouraged her husband to name her to his Cabinet; in 1991, she was made Secretary of Labor.

Long a supporter of Planned Parenthood, Barbara Bush knew that her earlier record of being pro-choice would become an issue raised in the media since it conflicted with the President’s stated views.

She carefully sidestepped the issue, particularly watching her words so that she did not go on the record as First Lady as being in agreement with her husband – or as being pro-choice.

When asked about a large pro-choice rally taking place in Washington, she snapped, “That’s what America is about and it’s great.” The White House soon felt the need to clarify her remark as meaning she thought it was “great” that citizens voiced their opinions.

On abortion, however, the First Lady did say she was “grateful” when a court order permitted an abortion to be performed on a comatose woman when there was hope that it might lead to her recovery. While she also said that she was “pained” by the “number of abortions,” especially knowing the difficulty one of her sons was then having in adopting a child, she also supported abortion when “the life of the mother was at risk.”

While refusing to declare herself anti-abortion to placate conservative Republicans yet focusing questions about whether she was pro-choice on the larger impact to families, Barbara Bush won the praise of the executive director of the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), saying the First Lady was “thoughtful, caring, concerned and compassionate not only about children’s lives and the quality of the family but about the role of women in the society and the world at large.”

And Barbara Bush also spoke out in favor of equality in the U.S. Armed Forces: “I’m not opposed to women in combat – if they are capable of doing exactly the same thing the average man can do, like throw a hand grenade.”

HIV-AIDS Awareness:

In 1989, at a Whitman-Walker Clinic ceremony, First Lady Barbara Bush hugged a gay man with HIV-AIDS, after her famously holding a baby with HIV-AIDS.

Barbara Bush became the first political public figure to insist on being photographed with people with HIV to help break the misperception that one could “catch” it simply by human touch. Just three months after becoming First Lady she visited “Grandma’s House,” a local Washington care center for children. There, she asked to hold a baby born with HIV and posed for photographs that were transmitted around the world.

Barbara Bush and Laura Bush holding children with HIV-AIDS at Bryans House in Dallas, Texas

But she also embraced and advocated for those adults, specifically the largest demographic of those Americans with HIV-AIDS, gay men. After visiting “Grandma’s House” she went to Washington’s Whitman-Walker Clinic, which served the gay community and was at the forefront of care for men with HIV-AIDS. There she made the gesture of also hugging gay men with HIV-AIDS just as she had done with the baby, who had contracted it at birth.

“You can’t imagine what one hug from the First Lady is worth,” said the clinic’s director, “Here, the First Lady isn’t afraid – and that’s worth more than a thousand public service announcements.”

It wasn’t heroics or historic to her. It was human. As recounted in her memoirs:

“I especially remember a young man who told us that he had been asked to leave his church studies when it was discovered he had AIDS. His parents had also disowned him, and he said he longed to be hugged again by his mother. A poor substitute, I hugged that darling young man … But what he really needed was family.”

In the White House Map Room, First Lady Barbara Bush listens to a woman describe the symbols in a portion of the larger AIDS quilt made to memorialize a family member.

Mrs. Bush made a second visit to children with HIV-AIDS, at a Dallas, Texas clinic joined by her daughter-in-law Laura Bush. She became the highest profile figure to attend the funeral of young Ryan White, who had suffered not just with the disease but the stigma and became a brave, young voice for those living with AIDS.

She and the President went to the National Institutes of Health to visit gay men with HIV and had photographs taken with them that were distributed to, and printed in the press. She welcomed a gay man’s family with the quilt they made in the White House, placed candles in every White House window as a public sign of solidarity with an AIDS memorial night vigil at the Lincoln Memorial, where gatherers held candles.

On policy, she successfully advocated that there be a sharp increase in AIDS research in the National Institute of Health budget for 1990, 1991, 1992 and 1993, and that HIV be covered by the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The Death Penalty & Gun Violence:

Just after declaring she would refuse to answer any “politics and policy” questions, Barbara Bush was asked if she thought military assault rifles should be outlawed. “Absolutely,” she snapped right away, “I myself do not own a gun. I am afraid of them.”

Her opinion seemed to contradict the stated policy of her husband. Or at least, what had been his view.

Weeks later, President Bush called for a temporary ban on military assault rifle importations. “Thank God for Barbara Bush,” the Washington, D.C. chief of police declared. “Listen to Barbara,” offered Senator Paul Simon.

And, after considering the increasingly detrimental impact of larger and more dangerous drug sales in the United States, she firmly offered that “proven” drug kingpins should be given the death penalty, “which stuns me because I don’t believe in killing anyone. But one of them kills many more individuals.”

Opposed English as Official Language:

In 2016, Barbara Bush joined daughter-in-law Columba and grandchildren George P. and Noelle, to watch their son, husband and father Jeb Bush announce his candidacy for the Republican nomination.

It was during her life in China, whe”At fifty, I tried to learn Chinese. It wasn’t easy,” Mrs. Bush later recalled.

Through her daughter-in-law Columba, a native of Mexico, wife of her son Jeb, the First Lady was especially sensitive to the literacy problems among the growing Latino and Hispanic populations in the U.S., while also proud of the fact that her three grandchildren through them all learned to speak Spanish first, then English.

Barbara Bush credited her life in China as immersing her entirely in a different culture.

She taped a public-service announcement aimed at them, and assuredly stated that their native language need not be relinquished by learning English as a means of having “the same advantages.”

While she wanted “every child in America to speak English,” she was adamant about it not becoming political. “I’m against legislation that would make English the official language because that has racist overtones,” said Mrs, Bus has First Lady.

Barbara Bush’s especially acute sensitivity to bigotry faced by Latino- and Hispanic-Americans was a direct result of not only the experiences of her grandchildren, but pride in their heritage. As Jeb Bush later explained,”We are very Hispanic, in that we speak Spanish in the house. Columba is a good Mexican, proud of her citizenship of this country, of course, but we eat Mexican food in the home. My children are Hispanic in many aspects. We don’t talk about it, but the Hispanic influence is an important part of my life.”

She later credited her years in China as teaching her not just to adapt to a new culture but to both recognize and seek out those human attributes that knew no barriers.

Homelessness:

Barbara Bush helped prevent the shutdown of Salvation Army fundraisers during the holiday season, 1989.

In her first weeks as First Lady, Barbara Bush made a visit to a local Virginia homeless shelter, both to donate used clothing and to meet with some of the residents, seeking to discern the causes of their being there. It was hardly her first visit to such a shelter, having taken a personal interest in the growing problem of homelessness during her eight years as Second Lady.

Among the ignored problems of one demographic she sought to address through literacy were those faced by single, working mothers – those who had no choice but to work in order to survive and support their children. “Many of them have babies without husbands, which makes it a tough row to hoe for them. And many of them are young, teen-age women who never had a chance to learn an occupation,” she put it plainly.

With children at a Goodwill event.

Barbara Bush found the challenges endemic to young, single mothers was the poverty that led to them and their children having to become homeless. It was something she had begun to notice during what proved to be dozens of trips, many unpublicized, to homeless shelters: We’ve got to acknowledge the fact – and do something about – thirty percent of our homeless are women with children.”

She also recognized the role of men in the issues of homelessness among such a large percentage of young, single mothers. “Men are not being made accountable for the children,” she declared, “it is absolutely outrageous.”

The First Lady offered her unequivocal support of more stringent child-support laws, a jurisdiction over which state and municipalities were the determinants and not the federal government. “We’ve collected enormous amounts of money and it’s just a drop in the hat for what’s being owned to those children [by their fathers]….They go on and have new families and don’t help the women [with whom they’ve previously had children.”

Reading to children who lived in a homeless shelter.

In considering those women of the working-class or living just above the poverty line who had to work to support themselves and their children, she believed that affordable daycare was a necessity that could help alleviate some of the struggle enduring by working mothers without the means to afford private daycare. Despite calls by many Republicans to gut federal funding for Head Start, created by the Democratic LBJ Administration, Barbara Bush stood up against that. She is credited with successfully insisting that Head Start federal funding not be touched.

As she did in analyzing the problems faced by young, single homeless mothers, she again made clear the responsibility could not all be placed on women. “Men are going to have to take a lot more responsibility.”

“You’ve got to be loving,” she said about the most fundamental aspect of parenting, “Men and women.”

Ringing the bell.

While she sought to ensure that the relatively small federal support that was funneled to homeless families through housing and education programs was not cut, she remained traditionally Republican on this issue, in believing that private charities and churches must assume the lion’s share of responsibility for local shelters. As such she was a lifelong supporter of the Salvation Army.

When a local Washington mall sought to do away with the bell-ringing and money pots of Salvation Army stands at the holiday season, the First Lady jumped in her limousine and headed to the mall, where she posed for pictures dropping some bills in the bucket. The charity was permitted to remain.

She, along with her husband, remained a strong supporter of the Salvation Army and even volunteered with him on some of their projects, including bell-ringing at the holiday season.

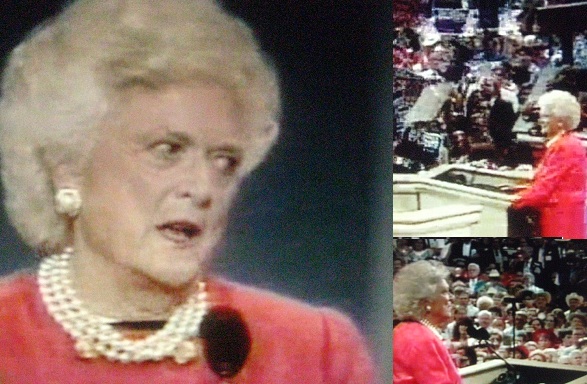

1992 Republican Convention Speech:

Barbara Bush speaking to delegates of the 1992 Republican National Convention.

Perhaps the humanitarian principals that guided Barbara Bush were best illustrated by her lengthy address to 1992 National Republican Convention that renominated her husband for another presidential term. She used it to redefine the concept of “family values,” a popular catchphrase of the era. It read in part:

“I’m here not to give a speech, but to have a conversation, and most of all, to thank hundreds of communities across the country for one of the great privileges George and I have had in the last four years the chance to meet so many American families and be in your homes. We have learned from you, and we look forward to meeting so many more of you with four more years. We’ve met…we’ve met thousands of wonderful families. When we speak of families, we include extended families, we mean the neighbors, even the community itself.

We’ve met heroic single mothers and fathers who have told us how hard it is to raise children when you’re doing it all alone. We’ve talked to grandparents who thought their childraising days were over, but are now raising their grandchildren because their children can’t. We’ve visited literacy classes where courageous parents were learning to read and continuing their education so they could make a better life for their families. And we’ve held crack babies and babies with AIDS and comforted other victims. George and I have seen communities gather around parents with a gravely ill child, helping them take care of the other children, helping them make it through each day. There’ve been many times in our own lives when we, too, couldn’t have made it without our friends and neighbors.

We shared moments with the families where the father and, indeed, the mother were serving in the Persian Gulf and heard stories of how their neighbors saw to it that the family left at home was taken care of, whether it was baby-sitting, helping with emergencies or even cutting the grass. Those yellow-ribboned towns not only wrapped trees and posts, they also wrapped their arms around these young families.

We have met so many different families, and yet, they really aren’t so very different. As in our family, as in American families everywhere, the parents we’ve met are determined to teach their children integrity, strength, responsibility, courage, sharing, love of God and pride in being an American.

However you define family, that’s what we mean by family values. You know, we know that parents have to cope with so much more in today’s world, more drugs, more violence, more promiscuity than when our children were growing up.

…No family is perfect, and no family is without pain and suffering. We lost a daughter; we almost lost a son, and one child struggled for years with a learning disability.

…George and I believe that while the White House is important, the country’s future is in your house, every house, all over America.”

Barbara Bush greets the cheering convention crowd after delivering her speech.

Categories: First Ladies

Tags: AIDS, Barbara Bush, George Bush, George W. Bush, homelessness, sexism

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders

Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health

Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health  Barbara Bush, Early 90s Icon: The Simpsons to The Laptop

Barbara Bush, Early 90s Icon: The Simpsons to The Laptop

Leave a Reply