Her favorite costar Cary Grant canoodles for a kiss from ambivalently amused Mae West in their 1934 film I’m No Angel.

“Love and sex are best together,” said Mae West. “But they ain’t so bad on their own neither.”

A promotional Valentine heart for the Mae West and W.C. Fields film My Little Chickadee.

On Valentine’s Day each year, Mae West could count on getting a heart-shaped box of chocolates, figuratively speaking, from the one person who truly loved her. Love in the sense of patience, devotion, appreciation, respect, and forgiveness. That person was Herself.

In the 1920s, she made the word “Sex” a household word, by using it as the title for her first full-length play, the topic being prostitution and the struggle of one Margie Lamont to get out of it. Sex was but one of the Jazz Age “sex plays” she wrote addressing a wide array of unspoken societal taboos which included rape (and her response to it, which was castration), homosexuality and transsexualism, interracial sexual intimacy, and the legitimized sexual exploitation of women.

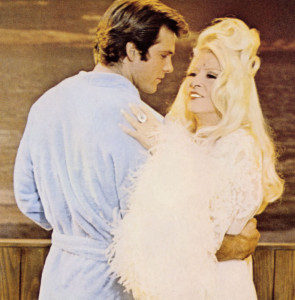

Giving the Frost: Mae West with 1936 co-star Randolph Scott. (Corbis)

In the 1930s, she touched a national nerve by subversively contradicting the masculine hierarchy when she cast herself in screenplays she wrote as the sexually provocative protagonist. As with all of Mae West’s characterizations, there were layers and layers of societal provocation tucked within her distracting use of comedy.

She used a pattern in these films.

In each, with handsome, gentlemanly costars including Cary Grant (She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel, both 1933), Roger Pryor (Belle of the Nineties, 1934) Paul Cavanaugh (Goin’ To Town, 1935), Phillip Reed (Klondike Annie, 1936), Randolph Scott (Go West Young Man, 1936) and Edmund Lowe (Every Day’s A Holiday, 1938) who become passively but hopelessly in love with her.

Oh yeah? Mae West with Edmund Lowe, 1938. (alamy)

She loved the attentive flirting, but she never entirely loved the men without a vast dose of skepticism. She never lost her head giving away her heart.

As each of her seven Paramount films nears its end, Mae West is looking ahead, but she’s not so sure where all their need for kissing will end up. Maybe she’d hang out some with them a bit longer, for the sex, because she was having fun. Maybe not. Maybe she’d stick around for good, for the love, because she’d fallen. Maybe not. She knew how they felt about her; she’d let ’em know how she felt in her own good time.

Looking him over something good: Paul Cavanaugh and Mae West, 1935.

Her Paramount films start with her being or becoming involved with one certain type of man: crude, thuggish, corrupt, jealous, shady, dishonest, deviant, aggressive and hot-tempered.

They were physically of either a brutish masculine character type or a meddling, troubled one. The dialogue and scenes make clear she’s having some kind of sexually intimate relationship with these chauvinists who serve her purposes for the moment, in some cases allowing herself to being a “kept” woman.

She could take him or leave him: Victor McLaglen, the rough sea captain and Mae West, 1936.

Looking out for herself is the priority, not living to some behavioral standard. The suggestion is that having sex to get what she needs wasn’t a problem, that sex was merely “an act” if it merely involved the physical.

Passionate kissing, however, involved the mind and that could get dangerously close to something entirely different. Love.

The more suggestive her movies felt to Hollywood censors, the stricter they became in forcing her adherence to the Hays Office code. While the power of her messages were buried deeper and deeper as the censors filtered her words and movement until her characterizations lost their bite, the rule insisting that kissing on film last no longer than three seconds and never be”passionate, lustful, or open- mouthed,” actually only helped her to more distinctly separate love from sex.

Cheek to cheek: Phillip Reed was one of Mae West’s sweet gents in 1936’s Klondike Annie.

And her kissing scenes follow a pattern. While it is the men who approach her for the kiss seemed to pass traditionalists as acceptable, her greater subtlety is seamless, typical of the brilliantly executed writing and performance of Mae West to telegraph an indelible yet subliminal message.

She might kiss with gusto, or kiss slowly – but she’d always glance with skepticism at the guy first. Sometimes, she physically pressed her arms against him, in initial resistance. If the kiss didn’t cut within three seconds and the scene would continue, she’d either pull away or more artfully use a prop to conceal what continued in private.

Kissing seemed a bit too sentimental and squishy for Mae West, a rather silly ritual that was alright for kids and old ladies. In her kissing scenes, she physically conveyed the act of a man stealing a kiss as a metaphor for being pinned.

Hang on buddy: Joseph Calleia tries to squeeze a kiss out of Mae West in 1940’s My Little Chickadee.

Mae West never got pinned, she was always on the go, always on for what lay ahead and she would either be in the process of moving on from a guy she’d gotten real sweet on, or would suggest she’d have no problem retaining her independence or would be up and out on her own just fine. Thanks, but no thanks. She didn’t need the commitment that a kiss from a man represented in that era.

And that’s also the premise of her most bitingly witty quips. In I’m No Angel, a maid observes that Mae West seemed to be a “one-man woman.” She agrees – “one man at a time.” When Cary Grant asks if she’d ever met the one man she could love. “Sure,” she smiles, “Lots of times.” She cracks in Every Day’s A Holiday, “Funny. Every man I meet wants to protect me. I can’t figure out what from.”

That no-good bum Ace Lamont: John Miljan gets a little too lovey in 1936’s Belle of the Nineties.

Mae West’s ideas on love and sex were adapted directly from her private life. In the Forties and into the start of the Fifties, as she had done throughout her adult life, Mae West did as she’d done throughout most of her adult life and had a string of physically intimate relationships. She casually made clear that these were driven by sex.

Yet she was extremely cautious to avoid love.

And there seems to have been a primal feminist reason for this, a reaction to the dominating societal expectations dictated by institutional sexism. As she would explain:

She didn’t bake: Mae West at the “Ideal Home Show,” in postwar England, 1946.

Through the years, as soon as I felt myself becoming infatuated, or what you think is in love with some man, then I’d break away from it. I don’t know whether it was that I never gave them a chance, you know what I mean, too long to be with one person. Because that I saw happen with people. You get a habit, you get used to a person, and feel you can’t live without them. I’ve seen women do that.

It goes against me. I can’t stand it! I get all nervous. And then I try to analyze myself and wonder, why? I never wanted to be a mother, never wanted to have a child. I felt that it would change me. It would change me mentally, physically, and psychologically. I would become a different person.

It may have been that I never cared that much for a man in particular to give your all. I’ll give you all – but for the time being. But that’s all.”

During rehearsals of their 1958 Academy Awards Show number, Mae West went in for the kiss more than she ended up doing during the broadcast. She seemed unsure how to react when he came in for a real kiss. (Life)

Even in her private life, Mae West was cautious to remain “in character,” especially when she knew she would be encountering fans and admirers. When she enjoyed a mass revival of fame and celebration in the late Sixties and early Seventies, as news broke that she was returning to the big screen for the first time in two decades, starring in the controversial film Myra Breckinridge, she began honoring a large number of interview requests.

American culture was then undergoing the Sexual Revolution. Men were growing their hair long, women were wearing pants. Many decided to live together without wanting the legal commitment of marriage, some were eschewing the shame of forming relationships of varying degrees with those of their own gender.

Never Too Young: Roger Herren and Mae West, 1970.

Mae West was especially riveted by discussions of the evolving moral codes, eager to provide her decades of acute observations of how love and sex could so quickly change the fundamental nature of human nature. Many journalists were disconcerted by the conservatism her observations suggest she believed in when it came to issues like radical feminism, overt sexuality and pornography.

Before Bond: Timothy Dalton in his first starring film as Mae West’s husband, in Sextette (1979) her last film. She died a year after it was released.

Just as most in the Twenties and Thirties had mistaken Mae West’s subversively expressed examinations of sexuality with the acts of sex, however, most in the Sixties and Seventies confused her conclusions about love with the acts of sex. Sex was necessary for love, love was necessary for marriage, marriage was necessary for permanence, permanence was necessary for family stability, family stability was necessary for all of society.

But none of that was necessary for everyone. “Marriage is a great institution,” she famously quipped. “I’m just not ready for an institution.”

She thought some women belonged there and did just fine, however: “When you see domestic women that married and have their children, that’s their life, that’s what they want to do. And that’s what they’re here for and that’s a wonderful thing. It would be terrible if every woman thought like I do, you know what I mean.”

She’d rather go write.

While her perspective makes her deepest emotional needs difficult to definitively discern, and she never let shame get in her way of enjoying dozens of short-term companions to satiate her healthy sexual appetite, she was extremely cautious about falling in love. Experience had proven to her earlier in her life that the egotistical men who fell in love with her eventually wanted to make her their wife. She feared it would challenge her larger mission of writing and performing for the masses, producing a body of work that is nothing short of social revolution through subliminal wit and suggestion.

That is, until she crossed the bridge of sunny maidenhood and met a man who loved her as much as she loved herself.

A mutual hold: muscleman Mae West and Paul Novak (then using the stage name of Chuck Krauser). She was the woman he loved who would never marry him for 26 years. (maewest.nl.com)

If there is any greater testament to the sacredness that Mae West truly held love it was her own longtime relationship with another gentler, handsome dude, Paul Novak. By the numbers attached to them each, she had twenty-six more than him, but neither cared about such mundane details. They first met when he joined the stable of muscle studs she hired for her 1950s Las Vegas act.

In full gender role reversal, he became dotingly devoted to her, never speaking to the press, gently escorting her to public events but always fading into the background so she could shine as the star at the center, He uplifted, protected and cared for her above all else.

At some point, after the Mae West Muscle Man Act finished a national nightclub tour, he moved into her lifetime home, a startlingly modest two-bedroom apartment.

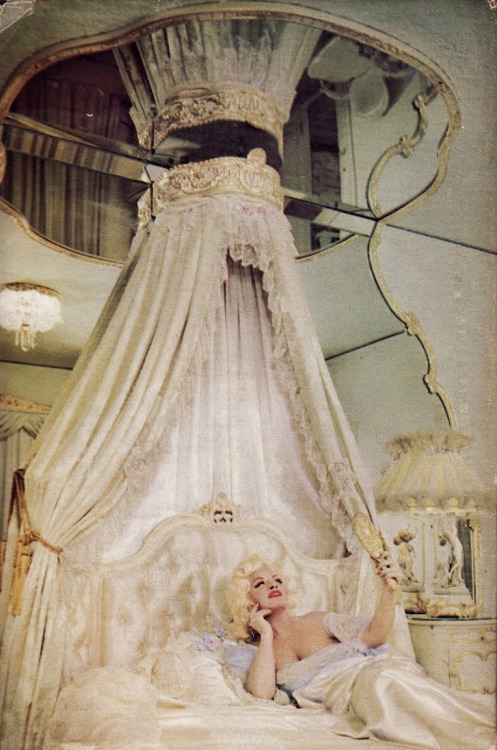

Room for two? Mae West in bed.

Speculation of all kinds wondered whether they slept apart or together, or just how intimate they were in private. Old-school style, neither of them detailed this for anyone else, but while their sexual intimacy remained a matter that was strictly private between them, their emotional intimacy was

Paul Novak would have loaded her with dozens of Valentine’s Day heart-shaped box of chocolates every year until the last one she marked, in 1980 – had it not been what drove him.

Love.

Just a few years after they met, Mae West learned that she had developed diabetes, a fact she did not enjoy acknowledging. It was Paul Novak who ensured that she avoid candy that she loved and other excess sugar, willing to challenge her formidable persona for the sake of her as a healthy person.

That was the kind of difference between love and sex that Mae West not only could understand, but appreciate.

He never kept her back: Paul Novak and Mae West in the late 1970s. (Getty)

One of the few people trusted into the heart of the small, discreet family that Novak and West created, Los Angeles Times writer Kevin Thomas recalled “Mr. Mae West” in a tribute at the time of his 1999death at age 76, as being “content to let the public believe he was merely West’s bodyguard, when in fact he became her husband in everything but name.”

Mae West insisted on keeping the nature of her relationship with Paul Novak a secret. She would only admit to a friend that Paul was “pretty terrific,” but even when making public events, it was clear by her bond with him that they were lifetime companions.

Paul Novak with Mae West at the premier of her last film in San Francisco, 1979. (wikipedia)

As her life went on, Mae West seemed to develop a better understanding of love while it was sex that became more bewildering.

“Love is what you make it and who you make it with…,” Mae West told reporters in September of 1947, as she disembarked from the Queen Mary upon her arrival in London for ten months.

Nearly thirty years later, in 1976, she quipped in her one and only broadcasted television interview four year before her death, “Sex? That’s no so simple.”

Categories: Legendary Americans, Mae West

To Know Mrs. Onassis: Why Jackie Kennedy’s Life as Art Endures

To Know Mrs. Onassis: Why Jackie Kennedy’s Life as Art Endures  Our Speakers of the House: Violent, Drunk, Lying, Cheating, Cursing

Our Speakers of the House: Violent, Drunk, Lying, Cheating, Cursing  Mae West New Year’s Eve, Partying Like It’s 1899

Mae West New Year’s Eve, Partying Like It’s 1899  Joe Namath: The Happy Hipster who Made the Superbowl Happen

Joe Namath: The Happy Hipster who Made the Superbowl Happen  Felix Baumgartner Left Earth Today to Free-Fall Thru the Sound Barrier…And History

Felix Baumgartner Left Earth Today to Free-Fall Thru the Sound Barrier…And History  Mae West Nude, Getting Naked, Fighting Father Time…and Living

Mae West Nude, Getting Naked, Fighting Father Time…and Living

Mae West was really on to something with her strong belief in “self love.” If you love and respect yourself, it is a short leap to extend that concept to those around you. Known not to run in “Hollywood” social circles, West surrounded herself with a fascinating cast of characters she forged strong bonds with, and with whom she enjoyed their loyal friendship in return. While the mention of Mae West’s name may not immediately resonate with young people today, the life lessons she exemplified such as discretion and resect for people from all backgrounds, are still essential character building blocks for people to adhere to. Thank you Carl, for this wonderful tribute to Miss West!

I greatly appreciate you taking the time to crystallize some very essential and important aspects of Mae West’s values and character. And actually I have seen evidence that very young people are discovering her and appreciating Mae West on many levels beyond the obvious one of comedic entertainment.