-

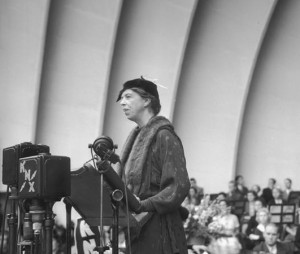

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt delivering her Sunday evening radio show from the White House Broadcast Room on the ground floor, as she did on December 7, 1941.

Terrorism. Refugees. Homeland protection. Fascism. Wartime preparation. Words from the White House.

Two days ago, Sunday, December 6, 2015, President Barack Obama addressed the nation on the burgeoning war on terrorism, following a deadly attack in California.

Seventy-three years ago today, President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers his declaration of war against Japan and its allies, to Congress.

Seventy-three years ago today, December 8, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation on the burgeoning war on fascism, following a deadly attack in Hawaii.

There was one other great difference between the two presidents, beyond the circumstances provoking their speeches.

One of them had First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt leading the way, speaking directly to the American people before the President.

Just hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, Mrs. Roosevelt trashed the text of her weekly Sunday afternoon radio show and wrote a new narrative, one of her most important and certainly one of her most eloquent public addresses.

The text of Mrs. Roosevelt’s Pearl Harbor Day speech.

Since the President did not go to Congress to deliver his declaration of war against Japan until noon the day after the attack, it was the First Lady who was not only the first to speak to the American people about how Pearl Harbor would radically change national life, but to do so in human terms.

There was no Internet. Newspapers could not be issued so quickly as to report the details of the attack. As far as instant news, there was only the radio.

And, on that frightening day many Decembers ago, as millions of Americans clicked on their radio, it was Mrs. Roosevelt who spoke to them as a familiar friend, despite her distinctively aristocratic Eastern seaboard accent.

The First Lady acknowledged the natural fear that citizens would now feel, and the inevitable sacrifices that would be necessary to defeat the rapidly rising global threat to freedom that the attack now inevitably drew the United States into combatting; a day after the President’s war declaration, Hitler and his Nazi Third Reich and Mussolini and his fascist-ruled Italy allied with Japan against the U.S., England, France and the Soviet Union.

She would give as good as she got. Hitler and Mussolini had been criticizing the First Lady for her persistent idealism about the essential fairness of the American people.

Here now is the full recording of her historic broadcast:

Mrs. Roosevelt’s Pearl Harbor speech was also a turning point in her relationship as First Lady with the nation at large.

Mrs. Roosevelt during the Depression, 1936.

During her first eight years as First Lady in the depths of the Great Depression, she was vilified for visibility. All First Ladies are political, but she was overt, expressing her opinion on contentious issues, involved in New Deal economic programs, advocating for greater legal equality between the genders and the races.

Eleanor Roosevelt delivering a speech at the Hollywood Bowl in 1935. (UCLA)

She did all this mostly in writing, through her daily newspaper and monthly magazine columns. It was listening to her voice as she spoke conversationally, however, which made instantly familiar to all Americans.

Even those who ignored her radio show, couldn’t avoid hearing her voice on the news, as she gave one of her thousands of public speech around the country. Her political nemesis and cousin Alice Longworth later confessed that she also tended to listen in, if only to be able to parody that distinct voice.

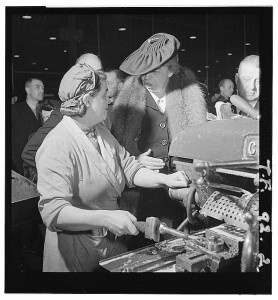

Mrs. Roosevelt chats up a “Rosie the Riveter” in a munitions factory.

Certainly, she seemed far more accessible than the President; his “fireside chats” numbered far less than than her regularly scheduled Sunday radio show broadcasts.

Leading by example, however, she soon became a national heroine in wartime.

In the White House, she kept all operations strictly in line with national rationing regulations, bought war bonds as gifts, started a victory garden and kept her gas mask at hand.

Always mindful of the hypocrisy of fighting oppressive tyranny while American laws kept women and minorities as second-class citizens, Eleanor Roosevelt used the war to advance their status however she could.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt supported the Civilian Pilot Training Program and the War Training Service. She is pictured here in a Piper J-3 Cub trainer with C. Alfred Chief Anderson, a pioneer black aviator and respected instructor at Tuskegee Institute. (U.S. Air Force photo)

She encouraged women to take factory jobs at weaponry factories as “Rosie the Riveters,” supported the formation of the African-American Tuskegee Airmen squads by riding in planes some of the program pilots flew and successfully insisted that wartime contracts must also be awarded to companies run by minorities.

Her words and deeds during World War II were not without controversy.

She visited Japanese-American families interned at camps to at least display her personal empathy with them against a program she considered racist and wrong.

Mrs. Roosevelt at Gila River, Arizona at a Japanese-American Internment Center.

She was an especially outspoken critic of her husband’s own State Department policies which refused to amend strict refugee and immigration quotas and permit those seeking asylum from Hitler’s Third Reich.

Eleanor Roosevelt visiting a rare American refugee camp located in Fort Ontario in Oswego, NY.

What made the situation all the more devastating to her was that she had heard more than a few reliable accounts of Jewish Germans and others being placed in restricted sections of cities and some being sent to “work camps.”

She knew that if they could they could be granted refugee status that their lives would likely be saved.

Mrs. Roosevelt was stunned when a bill permitting children in as refugees was defeated in Congress. That didn’t stop her, however. Instead of waiting for action by the State Department she began working on getting people in on a case-by-case basis.

Despite her work on policy matters, it was her symbolic role as she the traveled thousands of miles and sometimes in active war zones to personally visit American servicemen at bases from the United Kingdom to the South Pacific which won her nearly universal appeal.

Mrs. Roosevelt visits soldiers stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

With all four of her own adult sons on active military duty at the warfront, Stars and Stripes, the U.S. Army newspaper, declared that G.I.’s who met Mrs. Roosevelt felt she represented their mothers and responded to her with welcoming warmth. The First Lady’s visits to World War II servicemen is a large story in and of itself.

It all began, however, with her Pearl Harbor day broadcast. The subtext of her national message spoke up, rather than down, to the common man, conveying a dignified confidence, rather than unctuous pleading, that Americans would “rise above” their challenges and come together to defend freedom on not just the war front but the home front.

Mrs. Roosevelt speaking with migrant workers at the FSA Farmersville Camp, California.

The First Lady’s observations were fueled not by lazy nationalistic chanting but by the disciplined sacrifice of genuine patriotism.

It was about having come to trust their capacity to “meet an enemy no matter wherever he struck,” convinced the United States would win the war, based on “my faith in my fellow citizens.”

With an intensity she rarely expressed, Eleanor Roosevelt dramatically ends by declaring: “Whatever is asked of us, I’m sure we can accomplish….we are the free and unconquerable people of the United States of America.”

Leaving Franklin behind in DC, Eleanor was always on the go, go, go.

It was not naiveté or idealism that led her to this conclusion. With the President’s mobility limited by his infantile paralysis, she had been going and going, nonstop, touring the nation tirelessly for almost nine years before the war had started.

She was startled, awed and very often quite moved by the dedication, motivation and generosity of the people she saw and spoke with as they struggled with hope against the ravages of the depression.

Listening to that speech from three-quarters of a century ago, may also painfully beg the question of whether any president or presidential spouse of any political party could today speak with such conviction about the potential of our collective courage and willingness to sacrifice.

In honor of his birthday, this article is dedicated to my friend Byron Kennard, who met Mrs. Roosevelt and never forgot the experience.

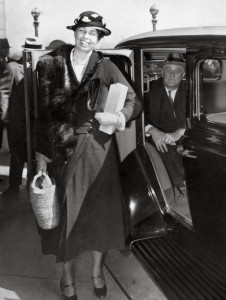

Eleanor Roosevelt smiles out at photographers from a White House limousine. (FDRL)

Categories: First Ladies, The Roosevelts

Tags: Eleanor Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Pearl Harbor, World War II

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders

Jane & Jill, Potential First Ladies: Lots in Common Between the Wives of Joe Biden & Bernie Sanders  All The Presidents’ Birthdays: Dance Balls to Movie Star Fundraisers in 90 Rare Photos

All The Presidents’ Birthdays: Dance Balls to Movie Star Fundraisers in 90 Rare Photos  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History

Melania Trump v. John Kelly: First Ladies & West Wing Personnel, A Brief History  Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health

Melania Trump’ Hospitalization: What the Public Is Told About a First Lady’s Health

Hi Carl!

I am sorry to comment here, but can’t seem to find a way to contact you directly. I just rented Mae West’s apartment at the Ravenswood, and would LOVE to talk to you. My email is [email protected]. I loved your post about meeting her…

Warmest

Kimberly

What a legacy she left us, the likes of which i’m afraid we will never see again. Now more than ever we must all become Eleanor for our children and grandchildren because Eleanor was all about HOPE!!

Wonderful broadcast which I’d never heard before. Thank you Carl for posting such a unique message on the anniversary of 1941’s attack.

I truly believe that the radio as the primary source of instant news was vastly more impressive than the 24/7 repetitive news cycles we have now. My parents and grandparents had photographs of them gathered in front of their big radios listening intently to broadcasts, both news and entertainment. I remember them saying after a broadcast, they would often sit and discuss it, and then return to their home life. Now, our tv’s are on all the time with background noise and soon we become numb to the words.

As a child of the tv era, I still remember the reverance of a radio report over the awkwardly produced television reports.

Somehow the radio made it ‘officially valid’. I often think we’d do better to return to that venue to filter out all the chaff!

thanks again Carl.

David Harris

Dear David – thank you very much for this. I apologize for the delay and the fact that many comments are being marked as spam and thus I only found yours and several others by looking there – I agree with you – there was something about the use of the imagination by hearing a news story read – by word only, without an image to cast a preconception. There was also something – as you suggest – very authoritative about that legendary “radio voice” of announcers – the way they stated the facts first, date, place, time, etc. Then again there were those in the 1920s who thought radio would signal the end of reading newspapers or promote illiteracy!