President Bill Clinton accepts the traditional Waterford glass bowl of St. Patrick’s Day shamrocks from Prime Minister Bruton in 1996.

Even if it took a century and a half, there were hopes to make the White House green from the start.

Jefferson had been a guest at the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick dinners and welcomed a delegation of Irish-Americans to the White House.

Just two years after George Washington took his oath of office as the nation’s first chief executive, there was an effort to at least make the President something of an honorary Irishman, for he was noted as having previously attended the annual St. Patrick’s Day dinner hosted by the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, a small but distinct group of veteran Revolutionary War leaders who strongly identified with Ireland, their nation of origin.

By the start of the 19th century, however, the organization had given way to the Hibernian Society for the Relief of Emigrants, a new group of immigrant and first-generation Irish-Americans seeking to encourage those on the Emerald Isle struggling in poverty to come to America, and help support them with food, jobs and housing.

One later but scant account claims that during his second St. Patrick’s Day as President in 1802, Thomas Jefferson either welcomed the Washington branch of the Hibernian Society to the White House or reviewed a militia composed of Irish-Americans.

It may be that it was the same group which was mentioned in a letter that day by New York’s U.S. Senator Samuel Mitchill, who recorded, “”As I walked out this morning I observed tho sons of Hiberniahad adorned their hats with the shamrock in honor of St. Patrick, their tutelary saint.”

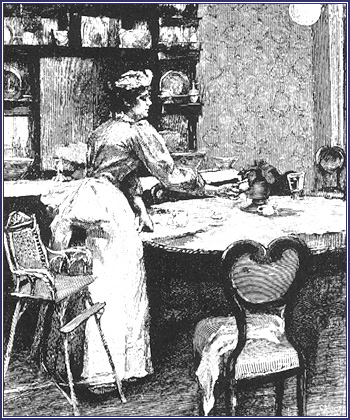

Many 19th century White House domestic staff members were Irish immigrants. (WHHA)

For more than a century afterwards, however, the only Irish pride in the White House was evidenced in the pantries, kitchens, horse stables, storage rooms and servant chambers where generations of immigrants from Ireland were lucky enough to find not only steady but prestigious work as cooks, maids, groomsmen, and other positions of domestic service, waiting on an increasing number of Presidents and First Ladies who could also claim relatively recent ancestry from Ireland.

The difference was that the First Families had parentage from northern Ireland’s Protestant immigrants (some of whom had first emigrated from Scotland to northern Ireland) while the majority of White House domestic help claimed it from southern Ireland’s Catholic immigrants. The first massive waves of Irish Catholic immigrants to the U.S. came in the 1840s. The sudden presence of such large numbers in American cities provoked a virulent backlash focused on the threat to American society.

Mary Todd Lincoln: no friend of the Irish.

The fear of many in the Protestant majority was that the Vatican was secretly planning to overthrow the government, based on the assumption that these immigrants were more loyal to “Rome” than their new homeland, and would carry out a plot hatched by the Pope to seize control of the U.S.

Fillmore later sought the presidency on an anti-Catholic platform. (millardfillmore.org)

While the White House never hung one of the ubiquitous “No Irish Need Apply,” shingles, belittling and disparaging remarks, if not outright bigotry about Irish servants can be found in the letters of First Ladies like Julia Tyler and Mary Lincoln, and the anti-Catholic political platform of former President Millard Fillmore during his failed attempt to regain the presidency.

Proving their patriotism in the ranks of the Union Army during the Civil War and then coalescing tremendous political power within the Democratic Party, however, the Irish in America began to earn the respect of Presidents.

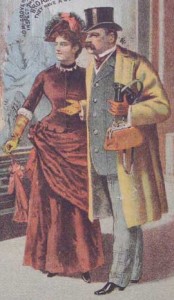

Don’t wear orange when meeting with Irish Catholic Democratic leaders, Frances Cleveland warned her husband.

When one morning Frances Cleveland wisely advised her husband to change out of a tawny-colored suit before his scheduled meeting with Democratic Party leaders, for example, Grover Cleveland immediately realized the wisdom of her sartorial suggestion that orange symbolized the northern Irish Protestants and might offend the southern Irish Catholics among the group.

Ellen Wilson urged her husband to ignore the anti-Catholic lobby and appoint Irish Catholic Joseph P. Tumulty as his Press Secretary, successfully making Democratic Woodrow Wilson recognize the political sagacity in doing so.

Republicans soon responded similarly.

Theodore Roosevelt formed a friendship with Baltimore’s Cardinal Gibbons, and was often seen at public ceremonies with him. William Howard Taft and Nellie Taft invited some of the nation’s most prominent and powerful Catholic clergy and business leaders to their White House Silver Wedding Anniversary in 1911.

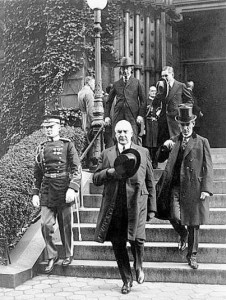

Harding exiting St. Patrick’s Church in Washington.

And in the 1920s, an era when a revived Ku Klux Klan boasted a national membership believed to have been in the hundreds of thousands, based in part on their new inclusion of Catholics as “anti-American,” President Warren G. Harding made the politically brave decision to attend a Catholic mass in Washington.

As he exited St. Patrick’s Church, historically the home parish to Irish-American community of the nation’s capital city, Harding walked out slowly and proud – with enough time for both still and newsreel cameramen to record his visit.

Within a decade, by the early 1930s, the Irish had finally earned the respect and honor from the White House that had for so long been evasive.

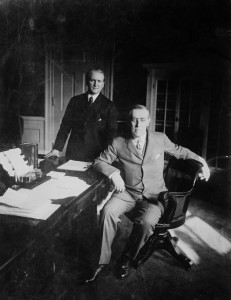

As the former governor of New York State and a close ally of his predecessor in that role, the Irish Catholic Al Smith, as well as an associate of Democratic Party leader James Farley, President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized not only the political power now held by Irish-Americans but also the contributions they had made to American life in one of his radio addresses to the nation.

Eleanor Roosevelt in an affectionate gesture towards her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt on St. Patrick’s Day 1941 in the Oval Office, which was also their 36th wedding anniversary.

St. Patrick’s Day also represented a special moment in his personal life: he had married his distant cousin Eleanor Roosevelt on the holiday in 1905.

When the couple posed together in the Oval Office on their wedding anniversary in 1941, the First Lady brought the President a gift of some shamrocks to mark the holiday as well.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s maternal grandfather Valentine Hall was the son of Irish immigrants and she remembered stories of how, despite the great wealth they earned as import merchants, her great-grandparents stashed great sums of cash in their furniture at home rather than banks, a habit she assumed they brought from Ireland.

Congressional candidate John F. Kennedy walking in south Boston’s St. Patrick’s Day parade. (Corbis)

In 1952, the Irish Ambassador decided to send a small box of shamrocks to President Truman and although he was away from the White House that day, he responded positively.

Seven years later, the first President of Ireland to come to the United States was welcomed by President Eisenhower and spontaneously pinned some shamrocks on Ike’s suit collar as a sign of unity between the two nations. The U.S. Embassy in Ireland has produced a video encapsulating the history of the evolving tradition.

Patrick J. Kennedy playing cards with friends in Boston, second from left. He was the President’s paternal grandfather.

In Boston, however, overtly celebrating St. Patrick’s Day had long been a custom for the United States Senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy, whose father had determined that he would be elected as the first Irish-American President of the United States.

The great-grandson of Irish Catholic immigrants on both sides of his family and the grandson of the famous Boston mayor John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, John F. Kennedy had been leading the march in Boston’s St. Patrick’s Day parades since he had first run for Congress in 1946.

While a US Senator, Jack Kennedy didn’t mind donning a green paper hat for St. Patrick’s Day.

Although loath to indulge in false sentiment about “being Irish,” JFK was proud of his heritage, a fact that seems borne out by the fact that, despite his dislike of ever being photographed in hats of any kind, he was willing to don one of those St. Patrick’s Day green paper hats which became so ubiquitous by the time he ran for the U.S. Senate in 1952.

Starting with the first of his three St. Patrick’s Days as President, John F. Kennedy invited representatives of Ireland into the Oval Office where he began the ceremony of accepting a bowl of shamrocks to mark the day.

In 1961,Kennedy became the first President to accept shamrocks on St. Patrick’s Day, starting a new tradition.

President Kennedy was also eager to learn more about his family’s Irish heritage which, beyond the bare facts, he had grown up knowing little about. For not only the nation’s Irish-Americans but many others with ancestries that were not of the Anglo Protestant majority, Kennedy’s election to the presidency, also marked by the civil rights era, signaled an growing sense that old prejudices barring them from the seats of power were falling.

For JFK as both a public figure and as a private person, there was no more emotional a moment in his presidency than his “homecoming,” the state visit he made to Ireland in June of 1963.

During that trip, Kennedy took time from an official schedule and motorcade to visit the humble farmhouse from which his great-grandparents had left in a state of hunger and poverty to immigrate to the United States.

Jackie Kennedy surprised her brother-in-law, Senator Robert F. Kennedy as he paraded up Fifth Avenue in the 1966 St. Patrick’s Day Parade. (Corbis)

After President Kennedy’s death, his connection to Ireland and pride in being Irish was further fortified by members of his family.

From the terrace of her apartment on Fifth Avenue, his widow Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis who was herself half Irish, watched the annual St. Patrick’s Day parade, once emotionally darting out into the middle of it, in the shopping district, when her brother-in-law U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was striding by.

The late president’s youngest sister, Jean Kennedy Smith would later be appointed the U.S. Ambassador to Ireland and his son, John Kennedy, Jr. always celebrated St. Patrick’s Day as a major holiday, and even got himself a shamrock tattoo on his leg.

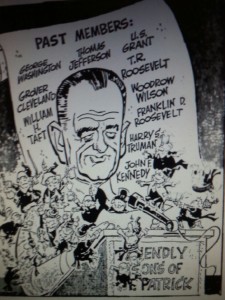

A cartoon heralding LBJ’s participation in a 1964 Sons of St. Patrick’s event.

For Presidents since Kennedy, the symbolism of St. Patrick’s Day also took on greater significance.

Just four months after he succeeded to the presidency upon JFK’s assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson attended a Friendly Sons of St. Patrick’s Day dinner, giving a toast to Irish-Americans, and also continued the tradition of receiving the ceremonial bowl of shamrocks.

As the twentieth century progressed, there was an increasing number of Presidents and First Ladies who claimed Irish ancestry and overtly celebrated it, most now being descendants of that first wave of Irish immigrants who had come to the United States during the potato famine in the 1840s.

Pat Nixon received her own Irish crystal vase of St. Patrick’s Day shamrocks – for her birthday. (AP)

With parental grandparents who were Irish Catholic immigrants, Mrs. Richard Nixon’s formal name was Thelma Catherine but because she had been born nearly at midnight on St. Patrick’s Day her father Will Ryan dubbed her his “St. Patrick’s Day babe in the morning,” and after his death she assumed the name “Pat” as her official name.

Nixon at the Curragh, Ireland

In the White House, Pat Nixon’s birthday was celebrated at annual St. Patrick’s Day parties and with her husband followed in the custom of President Kennedy by visiting their ancestral villages in Ireland.

Gerald Ford on St. Patrick’s Day.

Gerald Ford had to get his shamrocks pinned on him as he was leaving the White House, but Jimmy Carter resumed the formal custom and it has continued ever since.

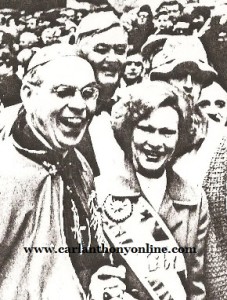

Rosalynn Carter in front of St. Patrick’s Cathedral with Cardinal Terence Cooke and Senator Patrick Moynihan before reviewing the annual parade.

In 1980, Rosalynn Carter, who is of part Irish ancestry, went on to become the first First Lady to serve as a marshal in the famous New York St. Patrick’s Day parade.

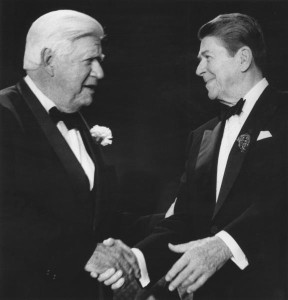

Although both George Bush and his son George W. Bush had very scant Irish ancestry, they continued the tradition of receiving Waterford crystal vases or bowls of shamrocks, Ronald Reagan took especial excitement in the annual holiday, especially proud of his father’s Irish Catholic heritage.

Reagan and Tip O’Neill shake on St. Patrick’s Day.

While he was always in political battle with Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, the two men quickly became good personal friends, bonding over their mutual Irish heritage and especially loved one-upping each other with barbed jokes reflective of Irish wit.

Reagan wearing the green.

When the Speaker decided to host a St. Patrick’s Day luncheon on Capitol Hill, Reagan was quick to accept the invitation to attend. In doing so, Reagan thus began another St. Patrick’s Day tradition followed by his successors.

Reagan enjoys a St. Patty’s Day beer at a local Washington pub.

Reagan also hosted St. Patrick’s Day gatherings among his White House staff, and one year, he was able to be slipped surreptitiously out of the White House by the Secret Service and make an impromptu visit at a local bar to hoist a beer with shocked but delighted patrons after work during “happy hour.”

On the occasion of his Chief of Staff Don Regan’s resignation under pressure, the President wrote him a farewell message quoting an Irish poem.

Reagan, like Kennedy and Nixon, made a sentimental visit to Ireland to visit the town from which his ancestors had immigrated to the United States.

So too did President Obama, after it was discovered by genealogists that he counted Irish immigrants among his maternal ancestors.

Obama would later quip that he’d wished this surprise had been learned sooner, when he was “running for office in Chicago,” where Irish-Americans take particular pride in their heritage, no matter how many generations back it might go.

Importing a famous St. Patrick’s Day custom from his home city, President Obama has had the White House fountains run with water dyed green, as is done annually in the Chicago River.

Among her own diverse ancestors, Michelle Obama also learned there was an Irish immigrant who settled in Georgia. Annually, the President and Mrs. Obama have held a large St. Patrick’s Day party in the White House, where even the lighting has been given a green tint to magically illuminate the rooms of the state floor.

No President seemed to take St. Patrick’s Day more to heart, however, than did Bill Clinton. Although his maternal Irish ancestry is an oral tradition, he always identified as Irish-American.

For Clinton, it was never merely about sentiment, for he determined early in his presidency to translate it into policy, helping to forge a permanent peace in Northern Ireland, where generations of Protestants and Catholics had been engaged in acts of terrorism in a struggle between formally remaining a part of England or breaking to be part of Ireland.

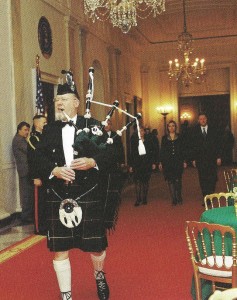

Bagpiper Richard Blair led the President and Mrs. Clinton into their 1998 St. Patrick’s Day reception.

Working with the British and Irish governments, President Clinton employed significant U.S. political and economic resources in support of peace.

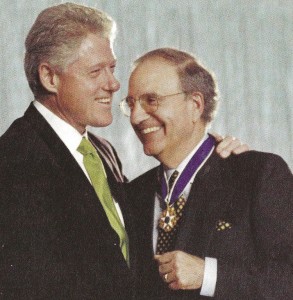

At the 1999 Clinton St. Patrick’s Day White House reception, the President awarded Senator George Mitchell with the Medal of Freedom for his role in the successful Northern Irish peace accord.

His own personal engagement, as well as the involvement of former Senator George Mitchell, who facilitated the multi-party talks, played an instrumental role in achieving the Good Friday Accord in April 1998 and overcoming hurdles to its implementation. The Accord represented the best hope in a generation for a just and lasting peace in Northern Ireland.

Historic progress was made in December 1999 with the formation of an inclusive government in Northern Ireland, acceptance of the principle of consent with respect to any change in the territorial status of Northern Ireland, the launching of new institutions for North/South cooperation on the island and the first steps to address the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons.

Hillary Clinton in a St. Patrick’s Day parade during her 2008 presidential campaign.

Hillary Clinton also played a dynamic role in the historic change, helping initiate and lead Vital Voices, an international organization which gave women a direct voice in the fate of their nations.

In the case of Northern Ireland, women came to play a huge role leading to peace.

In 1995, Bill and Hillary Clinton became the first President and First Lady to ever visit Northern Ireland, just after the case-fire.

It was their first of three visits there during his presidency.

Irish step-dancers lined the Cross Hall as President Clinton made his way to the 1998 St. Patrick’s Day.

In celebration of the evolving peace process during their years in the White House, Hillary Clinton decided to enlarge upon the annual presidential shamrock presentation ceremony.

President Clinton and Irish Prime Minister Albert Reynolds join in song during a State Dinner held in the latter’s honor, the day after St. Patrick’s Day 1994.

Starting in 1994, she began to host St. Patrick’s Day parties which became bigger as the years went by until, in 1999, the reception had to be held in a large tent on the South Lawn.

Bill and Hillary Clinton also invited a wide swath of Irish-Americans to their annual St. Patrick’s Day party.

Each year there was a menu featuring Irish classics like Colcannon potatoes, corned beef, kerry pies, boxty, soda bread and Guinness stout beers.

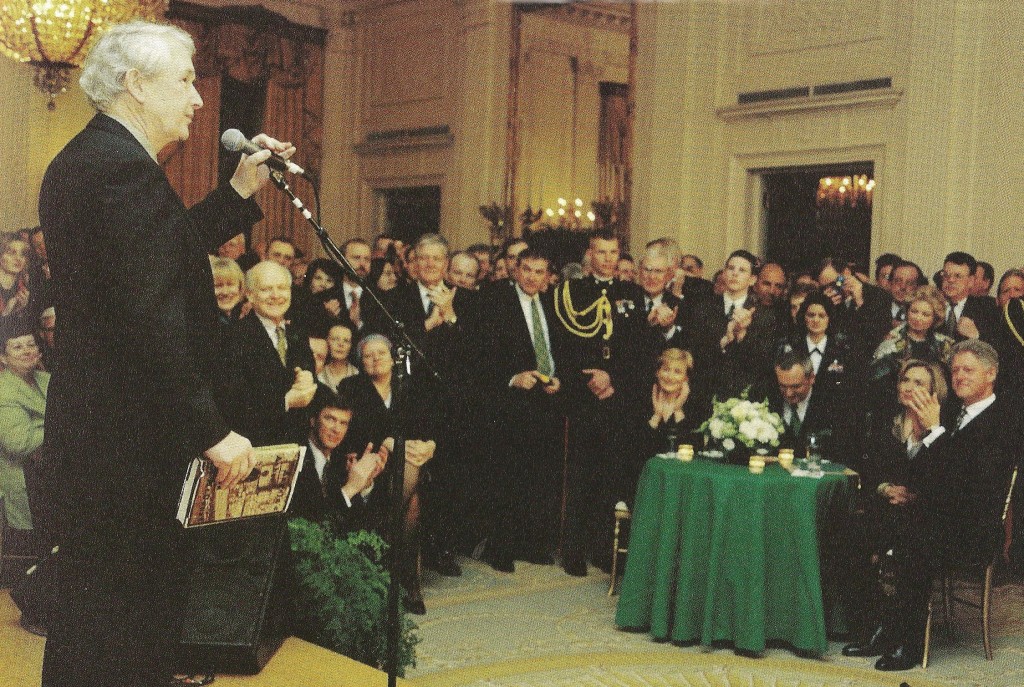

Frank McCourt read from his Pulitizer Prize winning books Angela’s Ashes, tlling of his impoverished lin in Limerick at the 1998 Clinton White House St. Patrick’s Day reception.

The Clintons also offered guests a variety of performing arts celebrating both the Irish and Irish-American experience.

There were choirs, step-dancers, bagpipers, singers and bands.

One year, they invited Nobel-Prize winning poet Seamus Heaney to recite from his work The Cure At Troy.

Another year, it was the Pulitzer-Prise winning author Frank McCourt reading from his work, Angela’s Ashes.

“Every St. Patrick’s Day party leaves us with unforgettable memories,” Hillary Clinton later wrote, “but perhaps the most powerful images I have are from the celebration in 1999. It was there that Claire Gallagher, an aspiring concert pianist who lost her sight in the 1998 Omagh bombing, expressed her dream of peace in a piano tribute she played with Phil Coulter.”

As fragile as history can often be, the peace has remained.

John Kennedy, Jr. with his cousin William Smith on St. Patrick’s Day in 1966.

Categories: Presidential Holidays, St. Patrick's Day, The Clintons, The Kennedys, The Nixons, The Reagans, The Roosevelts, Thomas Jefferson

Tags: Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Jacqueline Kennedy, John F Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, St. Patrick's Day, Thomas Jefferson

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit

Jackie & The Nixons: Mrs. Kennedy Returns to the White House, With New Images of the Visit  All The Presidents’ Birthdays: Dance Balls to Movie Star Fundraisers in 90 Rare Photos

All The Presidents’ Birthdays: Dance Balls to Movie Star Fundraisers in 90 Rare Photos  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part I  Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II

Liz Taylor Meets Jackie Kennedy: Tabloid Fantasy to Chance Encounter & The Only Photos of Them Together, Part II  The Nixon Family’s White House Halloween Parties of the Seventies: Pumpkin Pictures

The Nixon Family’s White House Halloween Parties of the Seventies: Pumpkin Pictures  Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Presidents, First Ladies & February’s Princess: Alice Roosevelt Longworth’s Century of Chief Executive Friends

Leave a Reply