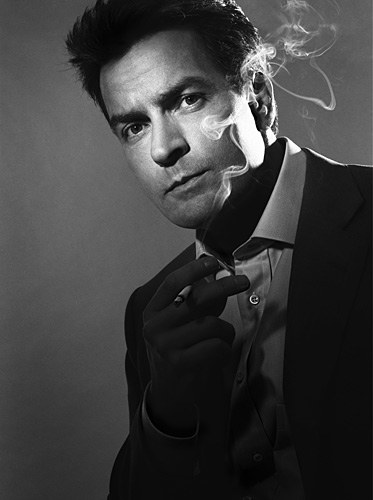

Charlie Sheen

In repossessing his previously successful persona, Charlie Sheen is now tweaking it into a narrative only Hollywood’s long-gone “Rogue” Archetype can play out. Whether search efforts for chards of the original Person have been abandoned only he knows; others only speculate.

Even before Monday’s CBS announcement he was fired from their sitcom Two and a Half Men, Sheen drew in over a million global Twitter followers from his most recent round of unapologetic drinking, sexing, drugging, and ranting. Doing it all publicly, conscious of the media reaction, puts him in league with three other Silver Screen Rogue legends whose eerily similar behavior heightened their popularity. It also taps a primal nerve going back at least to the cult of Dionysus, the Greek God of partying better known in Roman form as Bacchus.

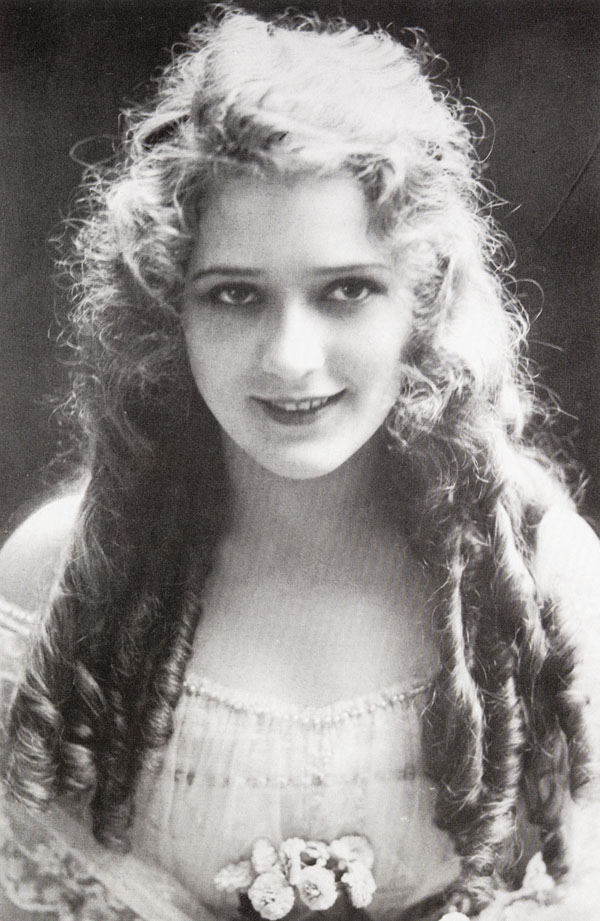

For a century, ever since the savvy little Gladys Smith, given the persona of “Mary Pickford,” was sold as “America’s Sweetheart,” Hollywood has bent a few actor attributes or deficiencies to craft their vaguely similar persona. If that persona busts the box-office, continuing to play to type can earn an actor big fame and wealth, but not without other risks. “I’m sick of Cinderella parts, of wearing rags and tatters. I want to wear smart clothes and play the lover,” Pickford soon enough unsuccessfully protested against her “Sweetheart” persona. “The little girl made me,” she later explained as the reason she quit acting, “I wasn’t waiting for the little girl to kill me.” Those with personas drawn closely from their authentic selves had less trouble adapting it in different roles. Jimmy Stewart, for example, was nearly always a character who reflected his personal warmth and honesty.

In contrast was Charlie Chaplin who developed his own iconic persona the “Little Tramp,” from a childhood spent in a homeless shelter and orphanage that forced him to use wit to overcome adversity. The “Tramp” was the ultimate comic hero; confounding authority to escape oppressive sadness. To working-class Americans, especially millions of impoverished immigrants, Chaplin and the Tramp were one. The hope he offered them wasn’t new. In his 423 B.C. play “Clouds,” Aristophanes gave Ancient Greek audiences the character of broke “Strepsiades” who confuses his money-lenders and slip from crushing debt. He reused the Archetype for a character called “Makemedo” in his play “Bird” nine years later.

Similarly, Mae West consciously created her own undulating and moaning “Diamond Lil” persona, in part to keep fresh the memory of her beloved Gay 90s mother. She found it such a useful armor to slip into for real life that many felt they were one and the same. The first actress (and writer) to subvert misogyny by being sexually assertive, it was no wonder West was called by some observors a modern Aphrodite, the Goddess who wore a magic golden girdle, got every man she wanted, and took many lovers.

The Chaplin and West personas distinctly endure because they came from authentic emotional truth within the real people they caricatured. The public wildly responded to both. Audiences found something instinctively familiar in them, as either “types” they knew or encountered or because they related to some universal truth in their struggle. Neither of them studied mythology to find an Archetype to emulate but elements of The Little Tramp and Diamond Lil, as well as some found in “good boy” Stewart or “good girl” Pickford among numeous other familiar Hollywood personae parallel figures from Greek mythology.

Yet even Gods, Goddesses and the mortals they interacted with weren’t just artificially conjured up by writers. They emerged from oral legends to explain nature’s mysteries, then used as the regular cast of characters in plays by philosophers trying to sensibly codify human nature. Audiences genuinely believed in, worshipped and idealized these Mount Olympus Gods, but also enjoyed the fact that, despite their power and glory, they had weaknesses, prejudices, bad kids, unfounded fears and foot pain. The same relationship exists today between global audiences and those they perceive to at least live like Gods, be they Presidential Families, High Society, Sport Figures or Business Tycoons. No arena, however, more consistently gives the world the full panoply of Archetypes with more dramatic stakes than does Charlie Sheen’s universe of Hollywood.

Too cynically willful to be like the saved, repentant “Bad Boy or Girl” (Colin Farrell, Brittany Spears), and too self-consciously sharp-tongued to be like the lost, doomed “Sad Clown” (Chris Farley, Anna Nicole Smith), Charlie Sheen is the “Rogue,” an Archetype of seasoned leading man whose power derives from talent, narcissism, charm and empathetic manipulation. Bravado convinces him he can both commit to convention as husband, father and hard-worker while indulging his vices, until he’s pressured by societal expectation to sacrifice the latter for the former. His lust for life overcoming his internalized horror of predictable stability, he makes a run for it, to bottle or boob, only looking up to smirk with arch pity at those doomed to die regretful for what they didn’t do. And then he turns his back in search of shinier bottles and boobs. When the indignant societal refrain rises, he sometimes returns to emphatically point out with self-proclaimed sound mind that his body is his own to methodically abuse – and life is meant to be enjoyed however one wishes. Or, as Charlie’s signature line goes, “Winning!”

A large part of the public interest in “Rogue” starring Charlie Sheen is novelty. It’s truly retro. By the mid-80s it proved too costly a production and studios turned it hybrid. The narrative still began as “Rogue” but ended in the new genre of “Rehab,” with a requisite public declaration of remorse for those hurt and a thirty-day cliffhanger ending as the sinner emerged from a recovery center. With Goodtime Charlie’s daily rants and poetic wordplay broadcast globally from his home, or public demonstrations of him waving a machete and swinging a bottle, his resurrection of “Rogue” offers secret relief to entertainment news producers and gossip rag editors fearing the tedious struggles of Lindsay Lohan will predictably peter out to prove Rehab rules. “Rouge” may be an Indie, but it gives “Rehab” a run for its money. Ironically, a more innocent America knew this Archetype well through a saintly troika of debauchery that Sheen so eerily now parallels that he just may round it out to make a Mount Rushmore, the fourth name to be added alongside John Barrymore and Errol Flynn and Richard Burton.

Granddaddy of Hollywood’s Rogue, John Barrymore stepped from theatrical stage to movie studio, bottle already in hand. Barrymore outran bankruptcy, nervous breakdowns and getting showgirl Evelyn Nesbit pregnant and then rushed to emergency “tonsilectomy.” Despite a growing list of exotic health problems from drinking, his good times were rudely interrupted by the a terribly pedestrian case of cirrhosis of the liver. From his deathbed in a Hollywood hospital, he cavalierly suggested mortality was beneath him: “Die? I should say not, dear fellow. No Barrymore would allow such a conventional thing to happen to him.”

“I like my whisky old and my women young,” snapped Errol Flynn, best remembered for playing a brashly dashing Robin Hood. His heavy drinking got him into a number of barroom brawls and his love of sex to a courtroom. Charged with statutory rape, his victories of the flesh were so legendary they were immortalized by the popular expression, “In like Flynn.” Not venereal disease, morphine or heroin addiction caused him regret: “I’ve had a hell of a lot of fun and I’ve enjoyed every minute of it.”

Not CBS but the BBC banned Richard Burton after his editorial rants questioning the sanity of Winston Churchill. Burton’s unquenchable sexual appetite included an elderly maid who was “almost toothless,” recalled co-star Joan Collins, one of the few to refuse him. Burton smoked up to five packs of cigarettes a day. He drank so heavily that the excessive alcohol levels in his system developed a spinal cyst, causing severe back pain that led to pain pill addiction. “I rather like my reputation, actually,” he confessed. “A spoiled genius from the Welsh gutter, a drunk, a womanizer; it’s rather an attractive image.” Burton rattled the Rogue’s demise a decade before wheezing his last real-life gasp, having relented to rehab in 1974 after a period of three daily vodka bottles.

In the 21st century its unlikely an actor with a hard-partying rep can even get to the level where he might attain the status of such an Archetype without, ironically, having first gone to Rehab, if only to prove he’s been there. Sheen’s done that three times (though being rushed to emergency care for cocaine overdose shouldn’t count), a fact he’s used to explain why he’s better off by just announcing to himself “I’m changed” at the “Sober Valley Lodge” (his home). He’s got a record, however, that already puts him in the Barrymore-Flynn-Burton league: a first illegitimate child at 19, a revoked college scholarship following arrest for credit card fraud and pot, firing a shot at a fiancé, charges of battering a porn star, domestic violence against his wife, dropping 50K on hookers. By his account, he’s been with 5,000 women. Declaring his party history “epic” he said it leaves Flynn looking like a “droopy-eyed, armless” child. “You should see how I party,” he said of a recent run.

What differentiates Sheen from Barrymore, Flynn and Burton, however, is that he never had an on-screen persona that paralleled the Rogue Archetype that he’s become as a real-life person. How then to explain his phenomenal public following which hundreds of public comments on online message boards and Twitter responses indicate to be overwhelmingly supportive? The answer might be found with civilization’s original Rogue, Greek God Dionysus whose obsession with drinking and womanizing was also intended to reveal a truth about enjoying life too much. In his play The Bacchae, Euripides warned against following the path which Dionysus tried to charm mortals down, shedding family commitments, work ethics and clothes along the way. One study described him as “protector of those who do not belong to conventional society and thus symbolizes everything which is chaotic, dangerous and unexpected, everything which escapes human reason…”

Apart from the entertaining aspect of Sheen’s spectacle, it might just be that, like Dionysus, he is dramatizing for his global audience a primal human conflict between pleasure and sobriety, underlining the danger of either too much cautionary self-regulation or carnal indulgence. In one recent message, Sheen seemed to parody the accusation he’s currently using cocaine. Maybe, like Dionysus, he’s using the Rogue Archetype to send a message about the right and responsibility of each individual to determine their own point of self-control and that the media has just assumed he’s not exercising any.

Perhaps. But it’s probably wise to remember that despite being granted all the privileges enjoyed by the Gods of Mount Olympus, including immortality, Dionysus partied so hard he actually became the first God to do something no other being up there ever did. He died. Or the fact that Barrymore died at 59, Flynn at 50 and Burton at 58. Charlie Sheen is still 45.

Categories: Americana, The Present Past

Tags: Charlie Chaplin, Charlie Sheen, charliesheen, Cult of Dionysus, Errol Flynn, Hollywood, John Barrymore, Lindsay Lohan, Little Tramp, Mae West, Mary Pickford, Movies, Richard Burton, Two and a Half Men

Presidential, First Lady, White House Memorabilia Auction Sale Now On

Presidential, First Lady, White House Memorabilia Auction Sale Now On  The Ignored Men Who Gave Women Their First Vote

The Ignored Men Who Gave Women Their First Vote  Songs Summarizing Summertime: Vote Your Favorite

Songs Summarizing Summertime: Vote Your Favorite  The Father of the Jellybean’s 1912 Black Peep Scandal: A Bittersweet Gem from the Archives

The Father of the Jellybean’s 1912 Black Peep Scandal: A Bittersweet Gem from the Archives  The Scruffy Dudes Who Got Wyoming Women the First Vote & Got Forgot

The Scruffy Dudes Who Got Wyoming Women the First Vote & Got Forgot  The Black Peep Scandal: An Easter Candy Mystery & The Father of the Jellybean

The Black Peep Scandal: An Easter Candy Mystery & The Father of the Jellybean

Leave a Reply